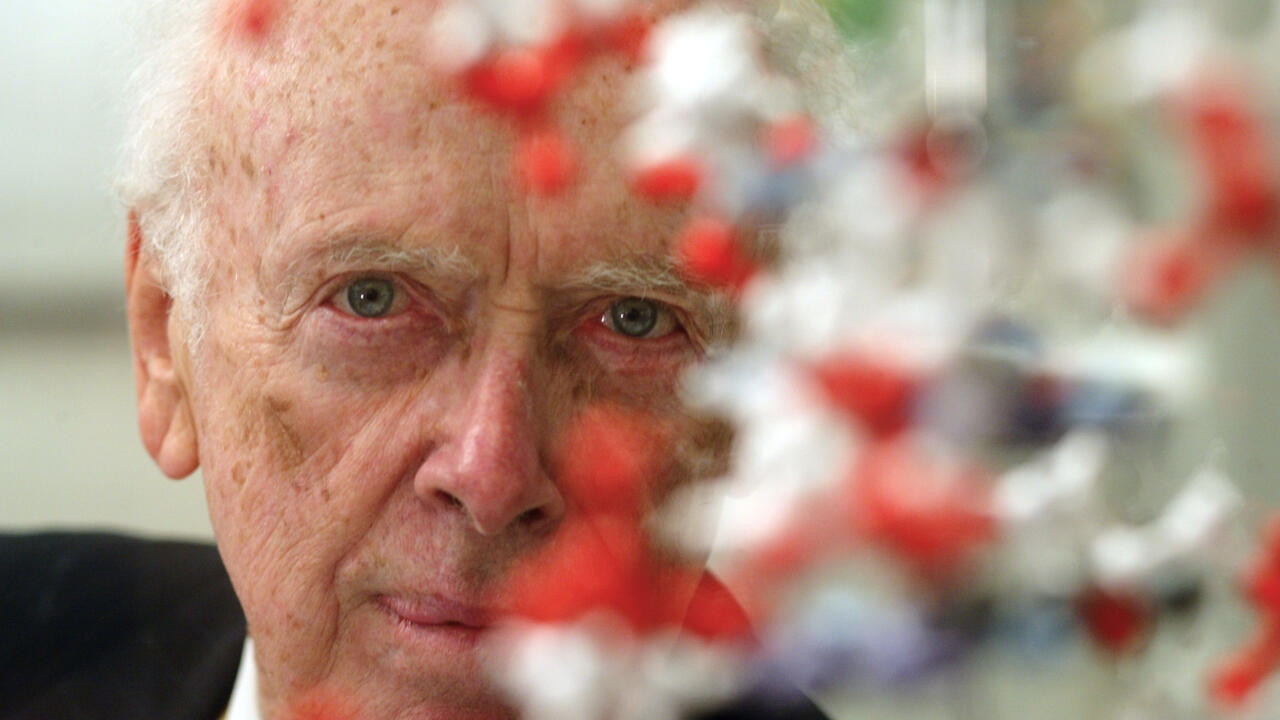

Immaculata Casimero at COP30 in Belém. She has attended three COPs to advocate for the rights and representation of Indigenous Peoples. Credit: Annabel Prokoyp/IPS

Immaculata Casimero at COP30 in Belém. She has attended three COPs to advocate for the rights and representation of Indigenous Peoples. Credit: Annabel Prokoyp/IPSBELÉM, Brazil, November 17 (IPS) - Immaculata Casimero, a leader of the Wapichan Women’s Movement, remembers the beauty of the mountains that are cultural sites to her indigenous community in Guyana.

Today, intensive mining has drastically altered their appearance. With no explicit access to prior informed consent, the projects came despite opposition from the Wapishana and other Indigenous people. Casimero says that the destruction caused by extracting resources for export to those who will never know the land is heartbreaking. It also draws parallels to the ongoing climate crisis negotiations.

COP30 in Belém is Casimero’s third Conference of the Parties. She is here advocating for the rights and representation of Indigenous people in global policy. It is clear that the process is flawed, sidelining local stories in global talks that instead amplify the voices of those who speak from a privileged vantage point. She demands a place at the table during the formulation of policies that affect communities.

“For me, as an Indigenous woman, I would like to see more of us at the grassroots level at the negotiating table,” Casimero said. “Because you cannot be deciding about our life, about where we live, at the national level or even at the global level. There should be inclusion of all voices at the ground level.”

The conversation further marginalizes women, who play crucial roles as environmental defenders in Casimero’s community but suffer greater consequences from mining.

She identifies a linkage, documented by the International Institute for Environment and Development, between the presence of mining companies and cases of gender-based violence. To further show the impacts of extractivism, Casimero points to a case in which communities were tested for mercury, a toxin that is a byproduct of gold mining, and found to have levels higher than the World Health Organization reference values.

This exposure has lasting implications on health and livelihoods, and in Casimero’s perspective, it is a product of historic exclusion from decision-making processes.

Negotiators in Belém are meeting to develop a Belém Action Mechanism to guide shifts from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources. It comes highly anticipated as a global path forward for a just energy transition.

However, Casimero is concerned about the intentions that drive these negotiations, citing the reliance of energy-intensive societies on the resources of indigenous communities.

“Those who need a just transition are the ones who are the polluters. When you’re talking about just transition, again, you’re talking about extracting minerals. But where is it coming from? It’s coming from Indigenous People’s lands again.”

She proposes an emphasis on a circular resource economy that relies less on continuous extraction and more on reuse of existing materials.

Casimero ultimately believes that the solution lies in bringing local voices to the global level.

“It’s talking to us, talking to the women, talking to the elders, and talking to the youths to see what is really important and how we are going to transition.”

However, she finds hope for a path forward in those who use their positions at the negotiating table to advocate for frameworks that recognize the demands of Indigenous people.

IPS UN Bureau Report

© Inter Press Service (20251117174136) — All Rights Reserved. Original source: Inter Press Service

1 week ago

4

1 week ago

4

English (US) ·

English (US) ·