Beijing is not aiming to dominate the growing collective of nations nor make it a tool against the West

By Ivan Zuenko, senior research fellow at MGIMO Univesity Institute of Institute for International Studies (Moscow)

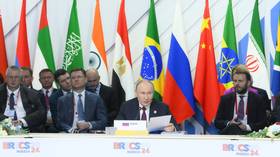

The 16th BRICS summit that took place in Kazan, Russia, became one of the most important meetings in the organization’s history. For the first time, an expanded group of participants took part in the summit (original BRICS members Russia, China, India, Brazil, and South Africa were joined by new members – the UAE, Iran, Egypt, and Ethiopia). Discussions about further expansion were also on the agenda, with Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, and Türkiye and other countries being considered as potential members.

Hosting such a high-profile forum represents a major diplomatic achievement for Moscow. As global leaders embrace Russian President Vladimir Putin, we see in this a striking symbol of the West’s failure to isolate Russia.

While all BRICS member countries play important roles in the organization, one stands out in particular – China, the world’s second-largest economy (and first in terms of purchasing power parity) and the United States’ primary rival for global influence. This raises an essential question: Is BRICS a tool for expanding China’s influence? And could it evolve into a sort of “Global South alliance” led by China against a “Global North” dominated by the US?

China’s official statements offer a more nuanced perspective on the matter, which we explore in more detail below.

What BRICS means for China

It’s important to understand that BRICS is a platform for dialogue rather than an alliance that imposes specific obligations on its members. It is unlikely that BRICS will transform into an integrated organization like the European Union. If any comparison is relevant, as a discussion forum, BRICS is closer to the G7.

There are several reasons for this. Firstly, among BRICS member states there are certain internal contradictions, and participation in the organization does not imply that these issues will be resolved. A good example is the territorial dispute between China and India, but there are other challenges as well. And as the organization expands – which seems inevitable – the number of these issues will only increase.

Secondly, creating alliances and tightly structured integrations contradicts China’s foreign policy philosophy, which rejects the old logic of “block opposition” in favor of developing “a new type of international relations” – partnerships between countries without binding agreements. According to China, the relationship between Russia and China exemplifies this approach, and is considered “stronger than traditional alliances”.

For China, complete sovereignty and the principle of non-interference in the domestic affairs of other countries (and vice-versa – resisting external interference in its domestic affairs) is paramount. China consistently applies this approach in its relations with other countries. It’s no coincidence that the Belt and Road Initiative, which has existed for over a decade, has not become an integrated alliance; it remains simply an “initiative”.

Implementing the initiative's the concept of a “community of a shared future for humankind” supposes the co-development of an unlimited number of countries based on mutual interaction. On the one hand, it implies integration (since it liberalizes the cross-border movement of capital, goods, and services); on the other hand, this form of integration respects the participants’ sovereignty and does not dictate which international organizations they should join.

China’s foreign policy philosophy does not rule out participation in various integration initiatives; in fact, it views them positively. And BRICS is one of them.

For China, BRICS primarily serves as a platform where Beijing can communicate its perspective on global issues to other nations and coordinate positions on various matters. Ultimately, the membership of other countries in BRICS (many of which have complicated relations with China) acts as a safeguard, preventing them from being pulled into Western coalitions that may be hostile towards China.

This approach prevents any possibility of China’s dominance. If Beijing were to form its own “pocket alliance” it would do so on its own terms, and would invite nations that are economically reliant on China. Meanwhile, Russia and India definitely don’t fit that category.

Does China need BRICS? It definitely does.

The key interests for China within BRICS include de-dollarization, establishing alternatives to the World Bank and the IMF, and helping the Global South break free from dependence on Western institutions. The BRICS platform facilitates these initiatives on a global scale and broadens their reach beyond a single region while minimizing the concerns of partners about potential risks associated with China’s expansion.

From this perspective, the more countries join BRICS, the better. Like Russia, China likes charts and graphs illustrating how BRICS nations collectively surpass G7 countries in terms of population and various economic indicators. This aligns with China’s view of the current phase in world history as one of “unprecedented change” characterized by the rise of former colonies and semi-colonies – changes that China believes could improve the world as a whole.

However, this doesn’t mean that China sees BRICS solely as an anti-Western bloc. It also hopes to engage with the West and foster mutually beneficial cooperation in the spirit of a “community of a shared future for humankind”.

Of course, at this point, there is no talk of EU countries, Australia, or Canada – nations that have strained relations with China —joining BRICS. However, if we consider the geographical expansion of the Belt and Road Initiative, it becomes clear that China is demonstrating flexibility and openness in matters of integration and is willing to collaborate with everyone.

This perspective suggests that China is not using BRICS as a tool to counter the US. On the contrary, as the organization expands, the likelihood of it transforming into a “military-political alliance” diminishes. However, as we’ve explained above, for China this is not a drawback but rather an advantage.

Why China’s participation in BRICS is important for Russia

China’s approach aligns well with Moscow’s political strategy. China does not hold a dominant position in BRICS when it comes to decision-making; all resolutions are made through mutual consensus, and Russia’s influence is equal to China’s.

However, China’s involvement makes BRICS (referred to in Chinese as “jinzhuang” or “golden brick”) a real alternative to what is often called the Western “golden billion”.

Without China, BRICS cannot represent the interests of the global majority, particularly in economic terms.

China serves as the primary trading partner and investor for most BRICS nations. Thus, initiatives aimed at streamlining trade among BRICS members can yield significant benefits only when they involve China. Proposals to switch to national currencies or create alternatives to the SWIFT system would be meaningless without China’s participation.

Investment projects linked to BRICS also become irrelevant in the absence of China. The New Development Bank, headquartered in Shanghai’s Lujiazui financial district, is largely funded by Chinese capital. Its projects in Russia include credit lines for the sustainable development of small historical towns, improving water supply systems in Volga basin cities, and enhancing transportation and logistics infrastructure in the Arctic region.

In short, access to China’s economic resources is particularly attractive to current and potential BRICS members, including Russia. Since this access is not direct but is ‘filtered’ through BRICS, this helps mitigate risks associated with dependence on financial institutions – not just Western, but also Chinese.

Even more importantly, the collaborative involvement of Russia and China in BRICS amplifies the impact of their bilateral strategic partnership, transforming it into a cornerstone for constructing a new world order based on multipolarity (China prefers the term “multilateralism” which, despite some nuances, conveys a similar idea).

Russia maintains close partnerships with all BRICS countries, yet China stands out as a permanent member of the UN Security Council that is capable of challenging the West in terms of the development of advanced technologies. Russia and China’s shared vision regarding the future of global politics, their ability to negotiate and resolve differences (which, like all sovereign states, they certainly have), and their openness to cooperation with other nations form the foundation of BRICS.

The strategic partnership between Russia and China has repeatedly been described by their leaders as “one of the key stabilizing factors on the global stage”. And within BRICS, this stabilizing effect becomes even more profound.

In the face of significant Western pressure on Russia, cooperation with China within BRICS takes on new meaning for Moscow. When Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping meet at bilateral summits, Western media talk of a supposed “alliance of two autocracies”. However, when they are joined by UN Secretary-General António Guterres, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, and other global leaders, it becomes difficult to maintain that narrative.

The recent BRICS summit in Kazan proves that relations between Russia and China are as strong as ever. This partnership is not one of a master and a subordinate – rather, it is an equal, mutually beneficial alliance that encourages collaboration with other nations. Fortunately, the appropriate framework for such partnerships already exists and continues to expand.

3 weeks ago

5

3 weeks ago

5

English (US) ·

English (US) ·