BBC

BBC

Operation Dudula has transformed from an anti-migrant pressure group into a political party

A community clinic just north of Johannesburg has become the frontline of a battle in South Africa over whether foreigners can access public health facilities.

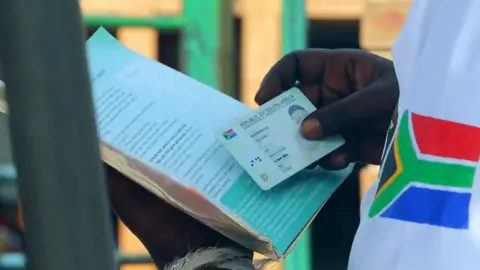

What started as a small local action in one area in 2022 has spread, with activists from the avowedly anti-migrant group, Operation Dudula, picketing some hospitals and clinics in Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal provinces. They check identity cards and stop anyone who is not South African from entering.

"Dudula" means to remove something by force in the Zulu language.

Despite some arrests, the authorities seem unable to prevent the pickets.

The site of their latest campaign is in Dieplsoot – a poor township of more than 200,000 people near the country's commercial hub.

On a cool, spring Thursday morning, Sicelokuhle Moyo, dressed in a blue-and-beige skirt, thick windbreaker and a black headwrap, set out early for the clinic.

The Zimbabwean, who has lived in South Africa since 2006, was going there, as she often did, to collect her medication for a chronic condition.

But this time, when she reached the gate, things were different.

Two men wearing white T-shirts emblazoned with the slogan "Operation Dudula – Mass Deportation" were stationed at the entrance. They demanded that everyone produce their documents before being allowed inside.

"I said that I had a passport. They said, they don't take passports. They want IDs only," Ms Moyo said, hiding her frustration behind a polite smile.

Despite this being a potential flashpoint, there was a strange calmness and resignation as people knew that Operation Dudula activists had been violent in the past.

Anyone unable to produce a South African ID book was turned away.

Slowly walking from the entrance, Ms Moyo joined a group of women by the roadside, young children tied to their backs, waiting with uncertainty for what would happen next.

Tendai Musvava, a woman in her 40s, faced the same fate.

"I was standing in the queue and then they said, they [only] need some people with IDs. Me, I don't have an ID. I have a passport, I am from Mozambique. So, I can't get my medication because I don't have an ID," she said.

Ms Musvava, dressed in a bright orange winter jumper and a white hat, appeared despondent.

"I just feel like they do what they want because it's their country. I don't have a say. For now I have to follow whatever they say. I don't have a choice."

South Africa is home to about 2.4 million migrants, just less than 4% of the population, according to official figures. Most come from neighbouring countries such as Lesotho, Zimbabwe and Mozambique, which have a history of providing migrant labour to their wealthy neighbour.

Xenophobia has long been an issue in South Africa which has been accompanied by occasional outbursts of deadly violence, and anti-migrant sentiment has become a key political talking-point.

Having started as a campaign, Operation Dudula, which has, at times, been accused of using force to make its point, is now a political party with ambitions to contest next year's local government elections.

Party leader Zandile Dabula insists that what her organisation is doing at public clinics in Johannesburg and other parts of the country is justified.

"We want prioritisation of South Africans. Emergency care - we understand that you must be treated - but if you are illegal you must be handed over to the law enforcers," she told the BBC.

When challenged with the fact that many migrants are in the country legally, she pivots to the argument that South Africans need to be prioritised because there are minimal resources.

"Life comes first, we don't deny that, but it cannot be a freebie for everyone. We cannot cater for the whole globe. We don't have enough."

The constitution guarantees the right to access healthcare for everyone in the country, regardless of nationality or immigration status.

But Ms Dabula says the public health system, which caters for almost 85% of the population, is overburdened.

She says that some people have to wake up at 04:00 to join long queues at their local clinic because they know that if they don't get there on time, there will be no medication left.

South Africa is a profoundly unequal society, with much of the country's wealth held in only a few hands. Unemployment and poverty levels are high and migrants, who often live in poor communities, are blamed by some for the problems people find themselves in.

Operation Dudula's methods have found a sympathetic hearing among some Diepsloot residents.

One of them, South African Sipho Mohale, described Operation Dudula's campaign as "a positive change".

"The previous time when I was here, the queue was very long. But this time around, it only took me a couple of minutes to get my stuff and get out," he said.

Another resident, Jennifer Shingange, also welcomed the activists' presence in Diepsloot.

"As South Africans, we would come to the clinic, only to find that the medication we need is not available. But since foreign nationals stopped using the clinic, there has been a difference," she said.

Ironically, some South Africans have not been spared from the anti-migrant campaign.

They too have been turned away from public health facilities because they could not produce an ID book – more than 10% of South Africans are thought not to have proper documents proving their nationality.

But it is the flouting of the constitution in Operation Dudula's actions that angers activists on the other side of the argument.

"To have a group that is not sanctioned by the state to make decisions about who gets in and who gets out is deeply problematic," said Fatima Hassan, a human rights lawyer from the organisation Health Justice Initiative.

"Unless government gets a handle on this situation quite soon, it's going to lose the ability to do law and order itself."

Deputy Health Minister Joe Phaahla told the BBC that his government was against the targeting of foreign nationals or anyone else trying to use local clinics and hospitals.

"We don't agree with that approach because health is a human right. As much as we understand the fact that the provision of services must be properly organised, you don't organise it through bullying kind of methods," he told the BBC.

Several major political parties, including the Economic Freedom Fighters and the Democratic Alliance, have also condemned Operation Dudula.

But a recent attempt to take it to court by the South African Human Rights Commission failed on a technicality, effectively allowing the group to continue its campaign.

Several Operation Dudula members have been arrested in recent weeks for blocking the entrances of public health facilities. They were later released with a warning. The police's action, however, does not appear to have deterred the group.

Ms Hassan believes that stronger action is required saying that "the police and the military should have been there on day one to prevent [the picketing] because that is simply lawlessness".

Dr Phaahla said this measure was being explored but the police have said resources are "stretched in terms of being able to monitor and intervene timeously when such incidents occur".

While the state hesitates over what to do, Operation Dudula appears emboldened and is turning its attention to public schools, saying that it is part of a campaign to fight illegal immigration.

But in Diepsloot, the group's action leaves people without the medical help they need.

Ms Musvava, who was turned away, is now looking for alternatives. Despite her meagre resources, she is considering going to the private sector.

"I think I'll have to go to the doctor. I will pay the money. I will have to sacrifice to get it," she said.

She had no idea how much it would cost her.

"I don't have money, but I will have to make a plan."

You may also be interested in:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC

6 hours ago

1

6 hours ago

1

English (US) ·

English (US) ·