Those found guilty of drug trafficking face the death penalty in Saudi Arabia. Of a total of 217 executions since the start of 2025, 144 have been put to death for drug-related offences.

If the pace of executions continues, this year’s total will surpass that of 2024, when 338 people were executed in the kingdom – the most since 1990.

At the heart of this crackdown is the illegal amphetamine-like drug captagon, very much in demand in the Middle East. And Saudi Arabia, the Arab world's largest economy, is one of its main consumers, according to the UN.

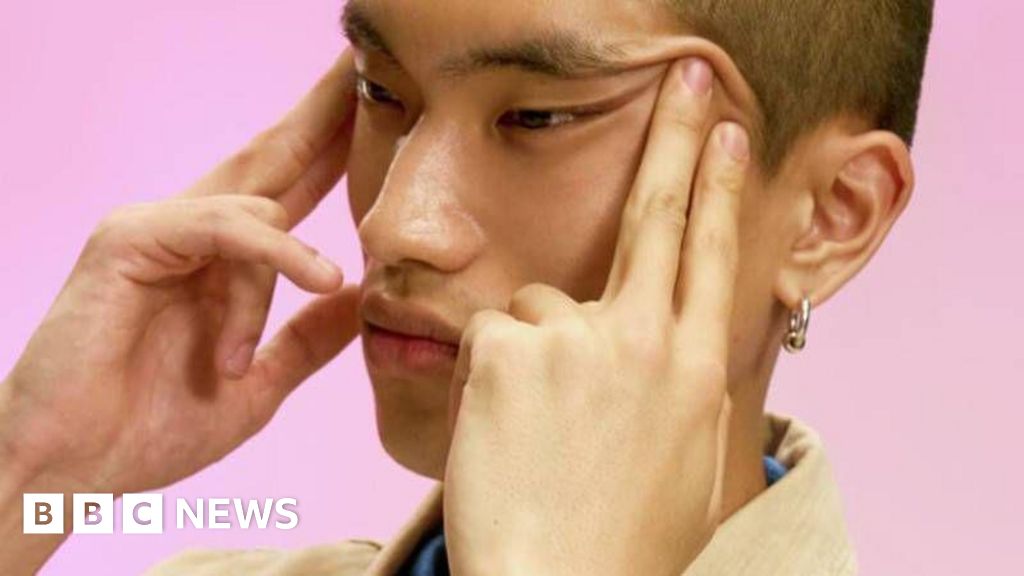

Captagon: Rich consumers, poor dealers

Captagon has become popular among wealthy young people in Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries, and is sold mainly by poor, immigrant dealers.

Saudi Arabia executed 37 people for drug-related offences in June, Amnesty International reported this month. Of these, 34 were nationals from Egypt, Ethiopia, Jordan, Nigeria, Pakistan, Somalia and Syria.

Read moreSaudi executes at least 338 people in 2024: AFP tally

“We are witnessing a truly horrifying trend, with foreign nationals being put to death at a startling rate for crimes that should never carry the death penalty,” said Kristine Beckerle, Amnesty’s deputy regional director for the Middle East and North Africa.

Human rights activists argue that capital punishment is detrimental to the image of tolerance and modernity that the kingdom seeks to project. And it seems to know this.

Following the global outcry over the 2018 murder of Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, Riyadh needed to do something to "polish” its international image, says Karim Sader, a political scientist and consultant specialising in the Gulf states. So it instituted a 33-month moratorium on executions for drug offences.

It resumed these executions in November 2022, and Sader says the recent surge in executions is largely due to the backlog that resulted from the suspension.

But the deaths of these foreign immigrant dealers “will attract far less media coverage than Saudi dissidents” sentenced to death for political reasons, he says.

‘The war on drugs justifies everything’

Domestic political concerns are the main rationale behind the current crusade against captagon, Sader says. Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman is concerned that Saudi society “will be corrupted by the scourge of drugs” and he wants to avoid this, “even if it means using brutal means and shocking international organisations – especially Western ones".

"The war on drugs justifies everything," Sader says.

Taking a hard line is also politically expedient, given that the crown prince – who initiated a modest opening up of Saudi Arabia’s authoritarian Islamic society – also has to contend with the “conservative fringes” of Saudi society.

For them, drug-related crimes should be punishable by death, Sader says.

"The Saudi authorities hope that by hitting hard enough, they will succeed in dissuading drug trafficking," he says.

The director of public security, Mohammed al-Bassami, in June reported "tangible positive results, with hard blows dealt to traffickers and smugglers", according to the influential Saudi daily Okaz.

But Sader suggests that a successful anti-drug campaign must be multi-pronged. "We know that in the face of the drug challenge, repression alone is not enough," he says.

The fall of Assad in Syria, the end of captagon in Arabia?

In the fight against captagon, sometimes called the "poor man's cocaine", Riyadh can count on at least one regional ally: Ahmed al-Sharaa, Syria’s interim president.

Read moreSyria destroys millions of captagon pills, other drugs: official

The day his rebel forces seized power in Damascus in December 2024, al-Sharaa referred to captagon in his victory speech. “Syria has become the biggest producer of captagon on Earth,” he said. “And today, Syria is going to be purified by the grace of God.”

During Syria’s 14-year-long civil war, captagon became the country’s most important export, according to an investigation by The New York Times.

Syria was producing 80 percent of the world’s captagon by 2023. It became so prevalent that some Arab countries agreed that year to normalise relations with President Bashar al-Assad if he promised that Syria would stop flooding the region with the drug.

Read moreWar on Captagon key to Syria's return to Arab League

Captagon production came to be the main source of revenue for Syria, a country shattered by war and hit hard by international sanctions. And Assad's closest allies – his brother Maher, in particular – were among the main beneficiaries of the multi-billion-dollar drug trade, which transformed Syria into a sort of “narco-state”.

Six months after the fall of Assad, the transitional Syrian authorities announced in June that all captagon production facilities had been seized.

Meanwhile in Lebanon, Hezbollah – which has also profited from captagon trafficking – has been considerably weakened by the war with Israel.

But while these trends might curtail the traffic in captagon, they are unlikely to bring an end to it.

"The fall of Assad and the weakening of Hezbollah will help to stop captagon being trafficked to Saudi Arabia,” Sader says. “But we will never be able to stop 100 percent of it.”

This article has been adapted from the original in French.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·