“On April 24, 2025, the United States determined … that the Government of Sudan used chemical weapons in 2024.” This is how the US State Department opened its May 22, 2025, statement announcing economic sanctions against the Sudanese government, which is under military control. No further details were provided to support the decision.

Khartoum denied the allegations the following day.

The New York Times had cited US officials in January as saying that the Sudanese army had used chemical weapons “that appeared to use chlorine gas” against the RSF (Rapid Support Forces) militia on at least two occasions in 2024. The officials gave no details.

Following the US sanctions announcement, several Arabic-language media outlets echoed these accusations. Unverified rumours and posts have circulated in Sudan, including claims of chemical weapons use in Khartoum. But until now, no documentary evidence of the army’s use of chlorine gas – or any other chemical weapon – has been made public.

Using open-source investigation techniques (OSINT), the FRANCE 24 Observers team in Paris examined two incidents in September 2024 in and near the al-Jaili oil refinery, north of Khartoum, which the army was attempting to recapture from the RSF. After reviewing images of the attacks gathered by the Observers, five experts confirmed they were consistent with aerial drops of chlorine barrels. Only the Sudanese army possesses the aircraft needed for such bombardments.

The Observers team also traced the origin of one of the chlorine barrels used in the attacks. Imported from India by a Sudanese company that provides supplies to the Sudanese army, the chlorine was intended, according to the Indian exporter, “solely for treatment of drinking water”. Chlorine is a much-needed humanitarian product in Sudan, critical for purifying water in a country prone to cholera outbreaks.

The military use of chlorine would place Sudan among the few regimes to have deployed this rudimentary lethal gas since World War I, during which it was used on a large scale. More recently, during the Syrian civil war, the world chemical watchdog, the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), found “reasonable grounds” to conclude that Bashar al-Assad’s regime used weaponised chlorine in rebel-held areas.

The two documented attacks in Sudan would also constitute a breach of the country's international obligations under the Chemical Weapons Convention, which it ratified in 1999. The use of “asphyxiating, poisonous or other gases” on the battlefield is also classified as a war crime under the 1998 Rome Statute, which defines offences that the International Criminal Court (ICC) can prosecute – though Sudan does not recognise the court’s jurisdiction.

At the time of publication, neither the Sudanese army nor the government had responded to FRANCE 24's requests for interviews.

The al-Jaili refinery was the target of chemical attacks: RSF

Following the announcement of the US sanctions in May, pro-RSF accounts on social media circulated images which they claimed showed the Sudanese army’s use of “chemical weapons”.

Some of these posts alleged that the attacks had taken place at the al-Jaili refinery in September 2024. The facility, which processes crude oil, is located 60 kilometres north of Khartoum. Operated in peacetime by the state-owned Khartoum Refinery Company, it is the largest refinery in Sudan and critical to the country’s fuel supply.

The country's civil war has disrupted the normal operation of the refinery. The RSF occupied it soon after the war began in April 2023, and a petroleum workers’ union said in May 2024 that it had been out of service since July 2023. The Sudanese army recaptured the facility on January 25, 2025, after months of heavy fighting.

On September 13, 2024, at the height of the clashes over control of the refinery, the RSF issued a statement accusing the Sudanese army of targeting the site with “an aerial bombardment by warplanes”, using “missiles suspected of being fitted with toxic gas, causing injuries and severe respiratory distress among dozens of workers”.

In the previous days, videos had circulated on pro-RSF accounts showing two yellow and green barrels found near the refinery.

A video published on Instagram on September 5, 2024 showed a barrel lying on sand, with a caption in Arabic: “The Sudanese army’s air force strikes civilians with weapons banned under international law, loaded with toxic and chemical gases.” Videos posted on September 13, 2024 showed a similar barrel beneath a tree.

Other posts from the same day showed workers receiving oxygen treatment.

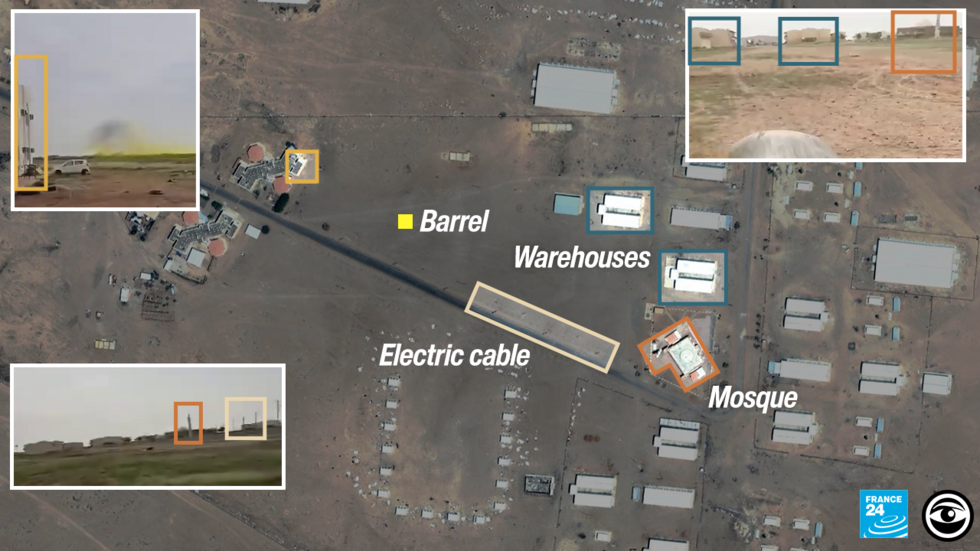

The Observers investigated the images to verify the RSF’s claims. Our team was able to geolocate the two barrels. The first was in a military base that had been occupied by the RSF, five kilometres east of the refinery. The second was within the refinery itself.

September 5: A barrel and a yellow cloud in an RSF-held base

On September 5, 2024, a pro-RSF account posted a one-minute video on Instagram showing an arid landscape surrounded by buildings. A visibly damaged barrel can be seen, bearing a yellow label with the words: “Oxidising agent 5.1.”

To display this content from , you must enable advertisement tracking and audience measurement.

A second video, posted on May 23, 2025, following the announcement of US sanctions, shows the same barrel from a different angle. A man first films a small crater in the ground, then a barrel a few metres away. He says:

“They fired something we don’t understand—maybe tear gas, maybe something else ... It released something yellow. We don’t know what it is.”

To display this content from , you must enable advertisement tracking and audience measurement.

Another video documents the moment when this “something yellow” is said to have escaped from the barrel. It shows a cloud of that colour, filmed at the same location as the crater and the barrel. Although the only available version of the video dates from May 2025, it was likely filmed just before the barrel footage. A logo on the video indicates that it was originally posted by a pro-RSF propaganda account on X, now deleted but still active on TikTok.

To display this content from , you must enable advertisement tracking and audience measurement.

All three videos were filmed inside the Garri military base, located 5 km east of the al-Jaili refinery.

The Observers also obtained images of the incident that were not posted on social media. Filmed from different angles, they show men in RSF uniforms, confirming that the base was under militia control at the time of the incident and therefore a strategic target for the army. Metadata from the photographer’s phone indicate that the images were recorded September 5, 2024 at 8:07 in the morning.

A barrel designed to carry chlorine gas

Although those who filmed the barrel claimed it had released “some kind of tear gas,” experts say it contained a much more dangerous substance: chlorine.

“These are clearly chlorine cylinders,” said Dan Kaszeta, a specialist in chemical defence. “This type of container is used all over the world for water treatment.”

Unlike many other chemical weapons, chlorine is widely used in industry. When released into the air, however, it causes rapid suffocation and can be lethal. “It is what we call a dual-use good – its use determines whether it becomes a weapon,” explained Matteo Guidotti, a chemist and chemical weapons expert.

Frederik Coghe, a ballistics expert and professor at the Royal Military Academy of Belgium, confirmed that the images from the Garri base show an industrial chlorine barrel.

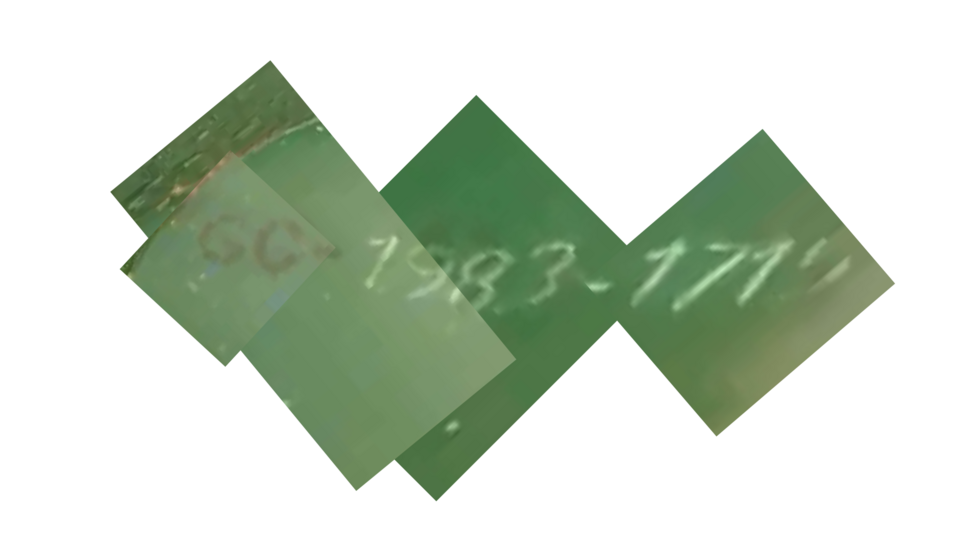

The footage of the barrel also shows a date, “20/5/24”, and a circular metal plate bearing a serial number: “GC-1983-1715.”

The Observers traced this “GC-1983-1715” barrel to an Indian exporter, Chemtrade International Corporation. The company confirmed that the barrel was tested for the last time on May 20, 2024, the date indicated on the barrel. A shipping document indicates that it was part of a consignment of 17 cylinders filled with liquid chlorine that were loaded onto a vessel in Mumbai on July 14, 2024 for delivery to Port Sudan. An e-mail received by Chemtrade indicates that the cargo was delivered in Port Sudan on August 17, 2024. The Indian supplier said the Sudanese importer had assured them the cylinders would be used “solely for drinking water treatment.”

A low-hanging yellow cloud – ‘consistent with chlorine gas’

Witness reports of a yellow gas leaking from the barrel and video footage showing a cloud of that colour spreading in the area further support the hypothesis of a chlorine attack.

To display this content from , you must enable advertisement tracking and audience measurement.

Three experts consulted by the Observers confirmed that the cloud is consistent with a chlorine leak. “Its colour is almost identical to what was observed in Aqaba, Jordan,” said Guidotti. On June 27, 2022, a chlorine container fell from a transport ship at Aqaba port, causing a massive release of gas that killed at least 14 people and injured 256 others.

“The colour of the cloud is consistent with what we would expect to see if chlorine gas was used, with a distinctive greenish-yellow colour,” added N. R. Jenzen-Jones, director of Armament Research Services (ARES), a technical intelligence consultancy specialised in arms and munitions. “The cloud also exhibits the characteristics of a gas that is denser than air, hanging low over ground. That, too, is consistent with chlorine gas,” he said.

September 13: A ‘toxic substance’ inside the refinery

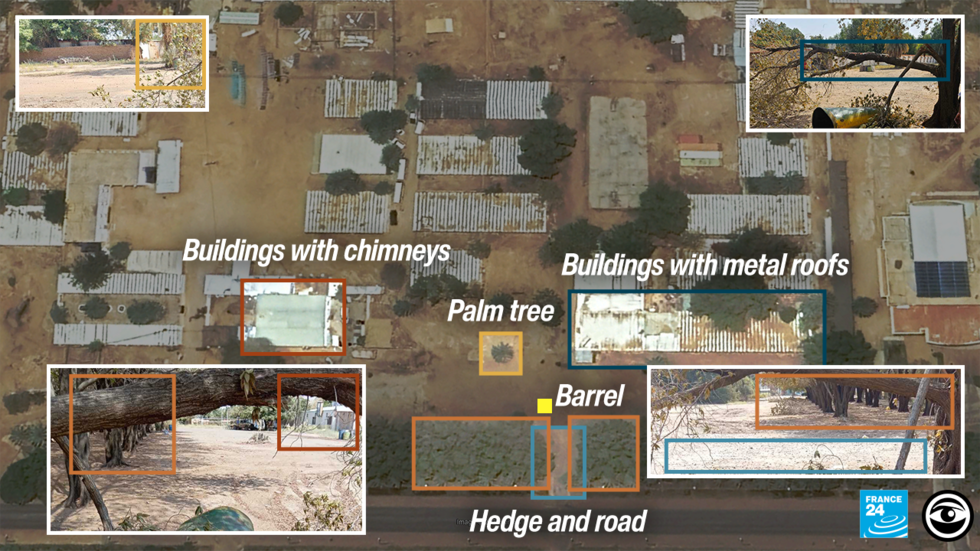

Other videos shared by pro-RSF accounts on September 13, 2024 – eight days after the first incident – show a similar barrel, this time beneath a tree. Men present at the scene filmed the object from several angles. One of them denounced what he described as the same type of attack as the one at the Garri military base.

“Last night the plane attacked us, guys. They dropped a gas cylinder on us…. Thanks to God, we’re fine for now, nothing has happened. But it was without any doubt an airstrike.”

To display this content from , you must enable advertisement tracking and audience measurement.

Another video showing the same barrel, filmed by a second man, alleged that the consequences of the attack had been far more serious:

“Last night, Friday September 13, the air force bombed the al-Jaili refinery. We, the workers and employees… were bombed inside the refinery by the air force. This barrel contained a toxic substance that escaped and spread in the air. Now several of us are in hospital, unconscious, in a very critical condition. Several may die.”

To display this content from X (Twitter), you must enable advertisement tracking and audience measurement.

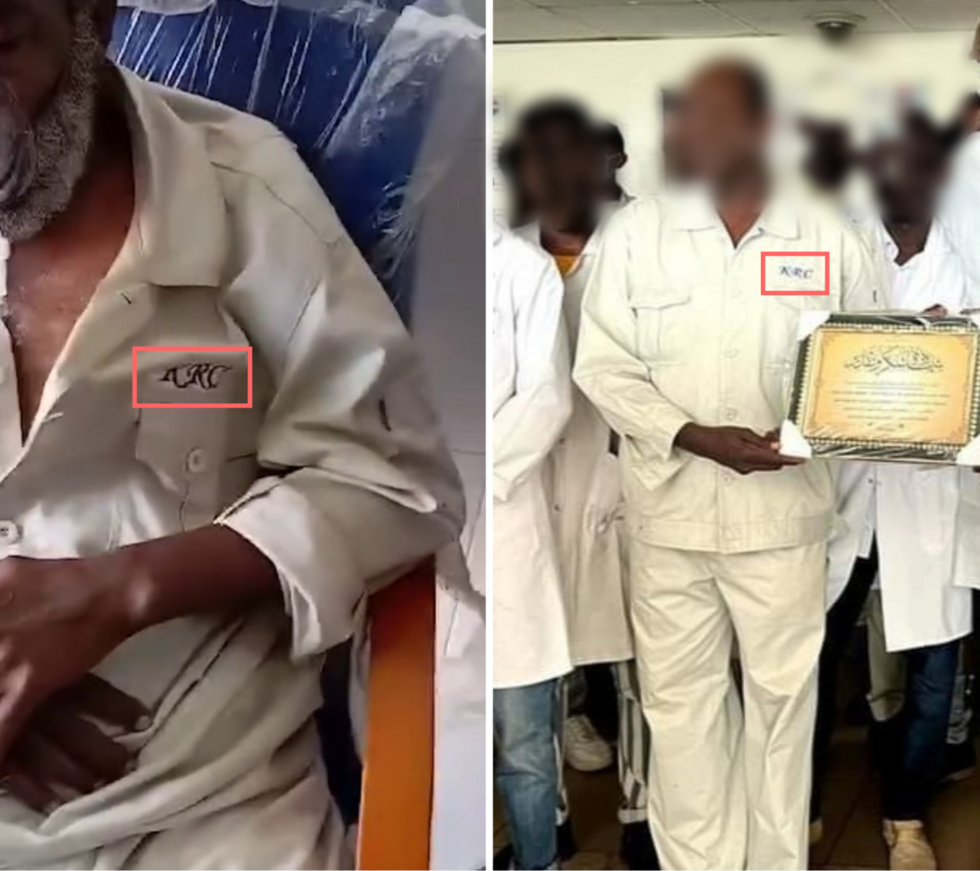

Footage shared on social media on September 13 shows at least six men – some wearing refinery uniforms – receiving oxygen treatment. There is, however, no indication of deaths or serious injuries linked to the incident.

To display this content from , you must enable advertisement tracking and audience measurement.

The videos showing uniformed men affected by the incident were filmed at the refinery’s staff clinic.

Other images provided by witnesses allowed the barrel-under-the-tree footage to be geolocated inside the refinery itself, among corrugated-roof buildings that appear to be workers' housing quarters.

‘People were unconscious, or struggling to breathe’

The Observers spoke with a former engineer who was inside the refinery on September 13, along with many other workers. For his safety, his name has been withheld. Now living abroad, he provided evidence of his employment at the al-Jaili refinery, as well as screenshots showing that he had reported the incident to contacts on the morning of September 13. By phone, he said:

“It was early, around 8am. I was in my room, where we were housed. I heard a plane coming, and then there was a huge noise, like something falling. I went outside with two friends, and I saw a lot of smoke. Luckily I wasn’t near the zone. After 30 minutes, we went to see the place where the projectiles had fallen. The people near them were unconscious, or having trouble breathing, and coughing. We helped them, with the security staff, and took them to the refinery’s clinic.”

The engineer’s account is consistent with the images and witness statements posted online. He also said that some of the victims died after the incident. The Observers team was unable to confirm this allegation, and no other sources mention any deaths in connection with the two incidents.

Chemical weapons specialist Dan Kaszeta also expressed caution about these assertions and the symptoms shown in the oxygen-treatment footage:

“The symptoms of chlorine gas exposure are relatively generic, with few clearly identifiable signs. In reality, it is very difficult to kill someone with this gas when it is dispersed in the open air, in this way. It is mostly used as a strong irritant, to force opponents out of shelters and make them vulnerable to conventional bombardment. That was how it was mostly used in Syria: during one chlorine attack in Douma, there were many deaths, but that was because the barrel exploded at the top of a building, asphyxiating those inside.”

The state of the barrels 'consistent with a drop from high altitude'

Accounts of an airdrop are corroborated by the videos of the event, in which several people refer to “air force bombardments”.

Jenzen-Jones also considers this scenario plausible:

“Either a helicopter or a fixed-wing aircraft could feasibly be used to deliver a chlorine payload contained in an industrial gas cylinder. Chlorine cylinders are generally stable and rigid, so they are fairly simple to transport and deliver out the back of a relatively slow-moving aircraft of either type. The impact with the ground is generally enough to rupture the types of industrial pressure vessels that contain chlorine gas. The challenge for the user is that this kind of delivery makes it very difficult to target a specific military objective.”

Visual clues also support the idea that the chlorine barrels found at the Garri military base on September 5 and inside the al-Jaili refinery on September 13 were dropped from the air. For example, the barrel at al-Jaili brought down branches from the tree above it as it fell.

The barrel found at the Garri base shows soil embedded in several dents, suggesting they were caused by a violent impact with the ground.

The Observers showed these images to Frederik Coghe, a ballistics expert and professor at the Royal Military Academy in Belgium. His assessment:

“All the containers sustained significant deformations and damage consistent with a drop from high altitude. At least one container shows major lateral abrasion, indicating a high horizontal speed at the moment of ground impact. To obtain this type of deformation, the containers must have been dropped from a transport aircraft or a helicopter flying at high speed. Faking these deformations would not be easy.”

This analysis was echoed by Trevor Ball, a former US army explosive ordnance disposal technician who now runs an open-source investigation account on X:

“The condition of these cylinders is consistent with the kind of damage one would expect following an airdrop. The cylinders are deformed, but mostly intact. […] In cases involving barrels of chemical substances dropped from aircraft, the crater size can be very small depending on altitude dropped, soil, and if the cylinders directly hit the ground or another object, such as a tree, first.”

The Sudanese army is the only force in the country with the aerial military capacity to carry out airdrops of chlorine barrels which weigh more than a tonne. RSF forces only have drones for bombings, which cannot carry loads exceeding 130kg.

While the army recently targeted cargo planes at the RSF-held Nyala airport in South Sudan, these aircraft were used solely for transporting troops and military equipment. There has been no documented evidence of the RSF conducting airstrikes with planes or helicopters, or using such aircraft for combat purposes.

'The explosion of any chlorine gas container will kill them slowly and silently'

Airdrops of these barrels were documented on social media by pro-RSF accounts from September 2024, but were also reported by outlets and channels favourable to the army.

On September 14, 2024, the day after the barrel fell inside the refinery, a pro-army media outlet claimed: “Army aviation is attacking groups of militia fighters in the housing units of engineers and technicians at the al-Jaili refinery.” A Telegram channel that supports the Sudanese armed forces and counts nearly 300,000 followers also reported air strikes on al-Jaili on September 13. That same channel had earlier announced strikes on the refinery on September 4, only hours before the incident at the Garri military base.

Other posts on the Telegram channel hinted that toxic gas had been released at the refinery. “Heavy artillery fire and air bombardments on the al-Jaili refinery by Antonov aircraft and fighter jets. The environment will become unbearable there with the build-up of gases resulting from burning oil and chemical substances… The explosion of any chlorine gas container will kill them slowly and silently,” read one message from the channel on September 10.

Two days later, on the eve of the al-Jaili incident, the same account boasted: “Resounding success in the testing of small ‘boum-ban’ in the area. The ‘claws’ [a nickname for RSF fighters] did not last more than 120 seconds.” The term “boum-ban” (البمبان in Arabic) is used in Sudan to describe tear-gas bombs and appears to be an oblique reference to munitions employing gas. Men at the Garri base on September 5 used the same local term when talking about the chlorine barrel.

To display this content from , you must enable advertisement tracking and audience measurement.

Two incidents compatible with chlorine attacks, according to five experts

Our investigation has found that industrial chlorine containers were dropped from the air on at least two occasions in the vicinity of the al-Jaili refinery, on September 5 and 13, 2024. At the time, the refinery was the scene of heavy fighting between the RSF and the Sudanese army.

According to RSF statements and pro-army posts, the army regularly bombarded the refinery and its environs in September 2024. Videos posted at the time show fires and substantial damage inside the complex. The army has consistently denied carrying out strikes on al-Jaili, instead accusing the RSF of destroying the refinery while occupying it by setting deliberate fires.

Five specialists in chemical weapons and ballistics consulted by the Observers all said that the images from Garri on September 5, 2024, and from the al-Jaili refinery on September 13 are compatible with chlorine gas attacks. They noted, however, that these indicators fall short of conclusive proof, and said that definitive verification would require immediate access to the sites. Guidotti noted:

“Half-an-hour after a bombardment, it is already too late to collect evidence of a chlorine attack, because the gas disperses naturally within minutes if there is any wind. In practice, this is probably the hardest kind of chemical weapon to identify — we saw that during the Syrian civil war. The only real solution would be blood tests on exposed people.”

Kaszeta expressed similar caution:

“These videos are not definitive proof. A yellow cloud, for example, can be mimicked with a coloured smoke grenade. There was one case in the Syrian civil war of a fabricated incident supposedly involving chlorine. I suspect that these two events [were chlorine attacks], but you can’t say more than that.”

Jenzen-Jones struck a slightly different tone:

“In this case the evidence is fairly convincing and points towards attacks using chlorine gas as a weapon. The repurposing of toxic industrial chemicals in combat is a trend that we have observed in recent decades. In Syria, most prominently, there was an extensive series of attacks which weaponised chlorine by dropping industrial containers from the air. It is perhaps, unfortunately, unsurprising to see this method of warfare adopted elsewhere.”

Sudanese government: 'There is no evidence of chemical or radioactive contamination in Khartoum State'

The Observers contacted the Sudanese army and government for comment. We also attempted to reach the US State Department to determine whether the sanctions announced in May 2025 were based on the incidents of September 5 and 13, 2024, at al-Jaili. A State Department spokesperson declined to comment, saying: “As is standard practice, we do not comment on alleged intelligence reports or discuss internal deliberations.”

After the US sanctions were announced on May 22, 2025, the army-controlled Sudanese government said it had formed a committee to investigate the accusations of chemical weapons use. The Sudanese health ministry, however, published a report in early September stating there was “no evidence of chemical or radioactive contamination in Khartoum state,” where the al-Jaili refinery is located.

“If the use of chemical weapons is confirmed, those responsible – both the perpetrators and decision-makers – could face criminal liability, including before the International Criminal Court if the UN Security Council so decides,” said Julia Grignon, an international law specialist and scientific director at the Institut de Recherche Stratégique de l’Ecole Militaire, a research institute affiliated with the French Ministry of Defence. “That has been done before: an arrest warrant was issued in 2009 for former Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir.” Sudan does not recognise the ICC’s authority: despite the warrant, al-Bashir was never extradited and remains detained in his country.

But how did these Indian industrial chlorine barrels end up in Sudan, to be used as chemical weapons? To answer that question, the Observers traced their path. Our investigation found that they were initially purchased by a company with ties to the Sudanese army, importing products manufactured by firms specialising in military equipment and weaponry.

Coming soon: Chemical weapons in Sudan 2/2: how did chlorine meant for water purification end up being used as a chemical weapon?

This article has been translated from the original in French.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·