TARASIVKA, Ukraine -- TARASIVKA, Ukraine (AP) — The Russian invasion of Ukraine has displaced millions, scattering families across the country and abroad. For many, heavy fighting in the east means crowded shelters, borrowed beds and fading hope.

About 400 miles west of the front line, however, a privately-built settlement near Kyiv offers a rare reprieve: stable housing, personal space and the dignity of a locked door.

This is Hansen Village. Its rows of modular homes provide housing for 2,000 people who are mostly displaced from occupied territories. Children ride bikes along paved lanes, passing amenities like a swimming pool, basketball court, health clinic and school.

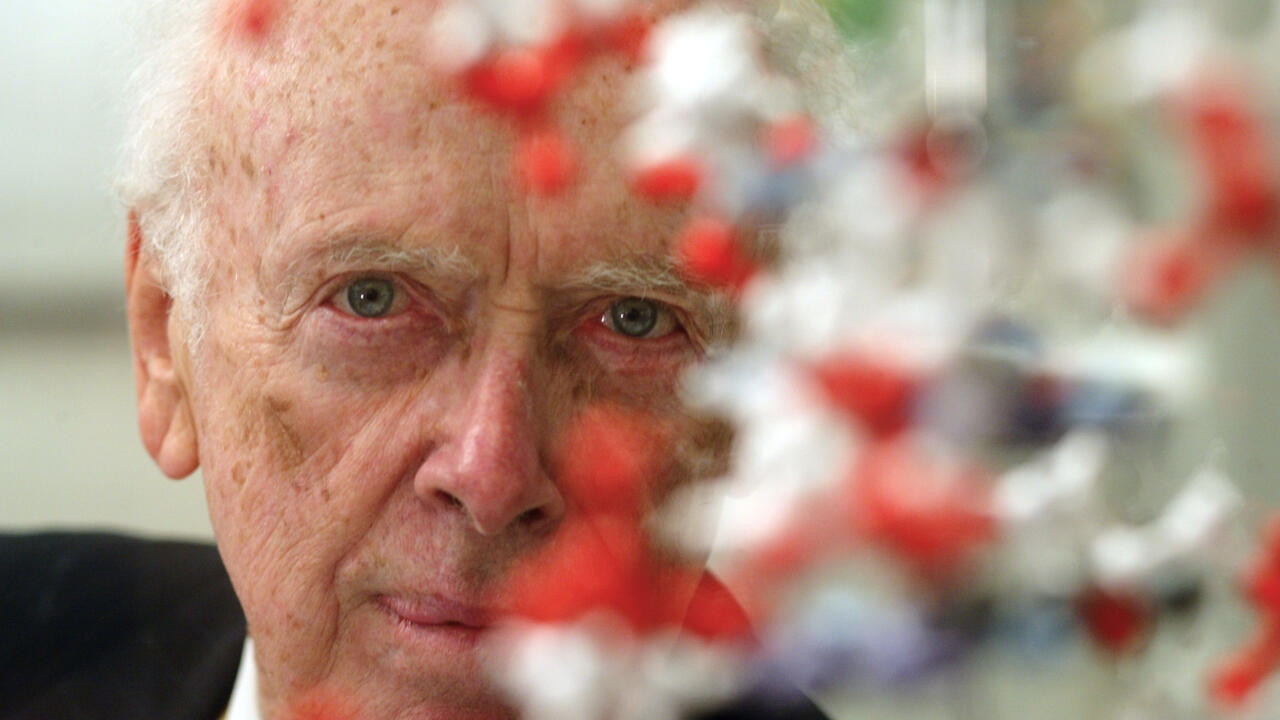

The village is the creation of Dell Loy Hansen, a Utah real estate developer who has spent over $140 million building and repairing homes across Ukraine since 2022.

At 72, he’s eager to do more.

Hansen’s arrival in Ukraine followed a public reckoning. In 2020, he sold his Major League Soccer team, Real Salt Lake, after reports that he made racist comments. He denied the allegations in an interview with The Associated Press but said the experience ultimately gave him a new mission.

“I went through something painful, but it gave me humility,” he said. “That humility led me to Ukraine.”

Seeing people lose everything, Hansen said he felt compelled to act. “This isn’t charity to me, it's responsibility,” he said. “If you can build, then build. Don’t just watch.”

Hansen now oversees more than a dozen projects in Ukraine: expanding Hansen Village, providing cash and other assistance to elderly people and families, and supporting a prosthetics clinic.

He's planning a cemetery to honor displaced people, and a not-for-profit affordable housing program designed to be scaled up nationally.

Ukraine’s housing crisis is staggering. Nearly one in three citizens have fled their homes, including 4.5 million registered as internally displaced.

Around the eastern city of Dnipro, volunteers convert old buildings into shelters as evacuees arrive daily from the war-torn Donbas region. One site — a crumbling Soviet-era dorm — now houses 149 elderly residents, mostly in their seventies and eighties.

Funding comes from a patchwork of donations: foreign aid, local charities and individual contributions including cash, volunteer labor or old appliances and boxes of food, all put together to meet urgent needs.

“I call it begging: knocking on every door, and explaining why each small thing is necessary,” said Veronika Chumak who runs the center. “But we keep going. Our mission is to restore people’s sense of life.”

Valentina Khusak, 86, was evacuated by charity volunteers from Myrnohrad, a coal-mining town, after Russian shelling cut off water and power. She lost her husband and son before the war.

“Maybe we’ll return home, maybe not,” she said. “What matters is that places like this exist — where the old and lonely are treated with warmth and respect.”

Ukraine's government is struggling to fund shelters and repairs as its relief budget buckles under relentless missile and drone attacks on infrastructure.

By late 2024, 13% of Ukrainian homes were damaged or destroyed, according to a U.N.-led assessment. The cost of national reconstruction is estimated to be $524 billion, nearly triple the country’s annual economic output.

Since June, Ukraine has evacuated over 100,000 more people from the east, expanding shelters and transit hubs. New evacuees are handed an emergency government subsidy payment of $260.

Yevhen Tuzov, who helped thousands find shelter during the 2022 siege of Mariupol, said many feel forgotten.

“Sometimes six strangers must live together in one small room,” Tuzov said. “For elderly people, this is humiliating.”

“What Hansen is doing is great — to build villages — but why can’t we do that too?”

Hansen began his work after visiting Ukraine in early 2022. He started by wiring cash aid to families, then used his decades of experience to build modular housing.

Mykyta Bogomol, 16, lives in foster care apartments at Hansen Village with seven other children and two dogs. He fled the southern Kherson region after Russian occupation and flooding.

“Life here is good,” he said. “During the occupation, it was terrifying. Soldiers forced kids into Russian schools. Here, I finally feel safe.”

Hansen visits Ukraine several times a year. From Salt Lake City, he spends hours daily on video calls, tracking war updates, coordinating aid, and lobbying U.S. lawmakers.

“I’ve built homes all my life, but nothing has meant more to me than this,” he said. “People here don’t need miracles — just a roof, safety, and someone who doesn’t give up on them.”

Last year, Hansen sold part of his businesses for $14 million — all of it, he said, went to Ukraine.

Still, his contribution is a fraction of what’s needed. With entire towns uninhabitable, private aid remains vital but insufficient.

Hansen has met with President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, who thanked him for supporting vulnerable communities. Later this year, Hansen will receive one of Ukraine’s highest civilian honors — an award he says is not for himself.

“I don’t need recognition,” he said. “If this award makes the elderly and displaced more visible, then it means something. Otherwise, it’s just a medal.”

___

Associated Press journalists Vasilisa Stepanenko and Dmytro Zhyhinas in Pavlohrad, Ukraine contributed to this report.

___

Follow AP’s coverage of the war in Ukraine at https://apnews.com/hub/russia-ukraine

1 month ago

18

1 month ago

18

English (US) ·

English (US) ·