EDITOR’S NOTE: This article is a translation of an article originally published in French on February 2. Since that date, journalist Carlos Julio Rojas has decided to speak out publicly on the television network NTN 24, breaking the ban on public comments that was imposed on him as a condition of his release.

On January 8, the president of Venezuela’s National Assembly, Jorge Rodríguez, declared that the government had decided to release a "significant number" of people. This announcement – made only five days after US Army special forces captured president Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores – was met with hope and expectation by the families of political prisoners. Many went to the detention centres to call for their release.

To display this content from X (Twitter), you must enable advertisement tracking and audience measurement.

Four weeks after this announcement, 350 political prisoners have been released, according to Venezuelan NGO Foro Penal, whose name translates to "Penal Forum".

To display this content from X (Twitter), you must enable advertisement tracking and audience measurement.

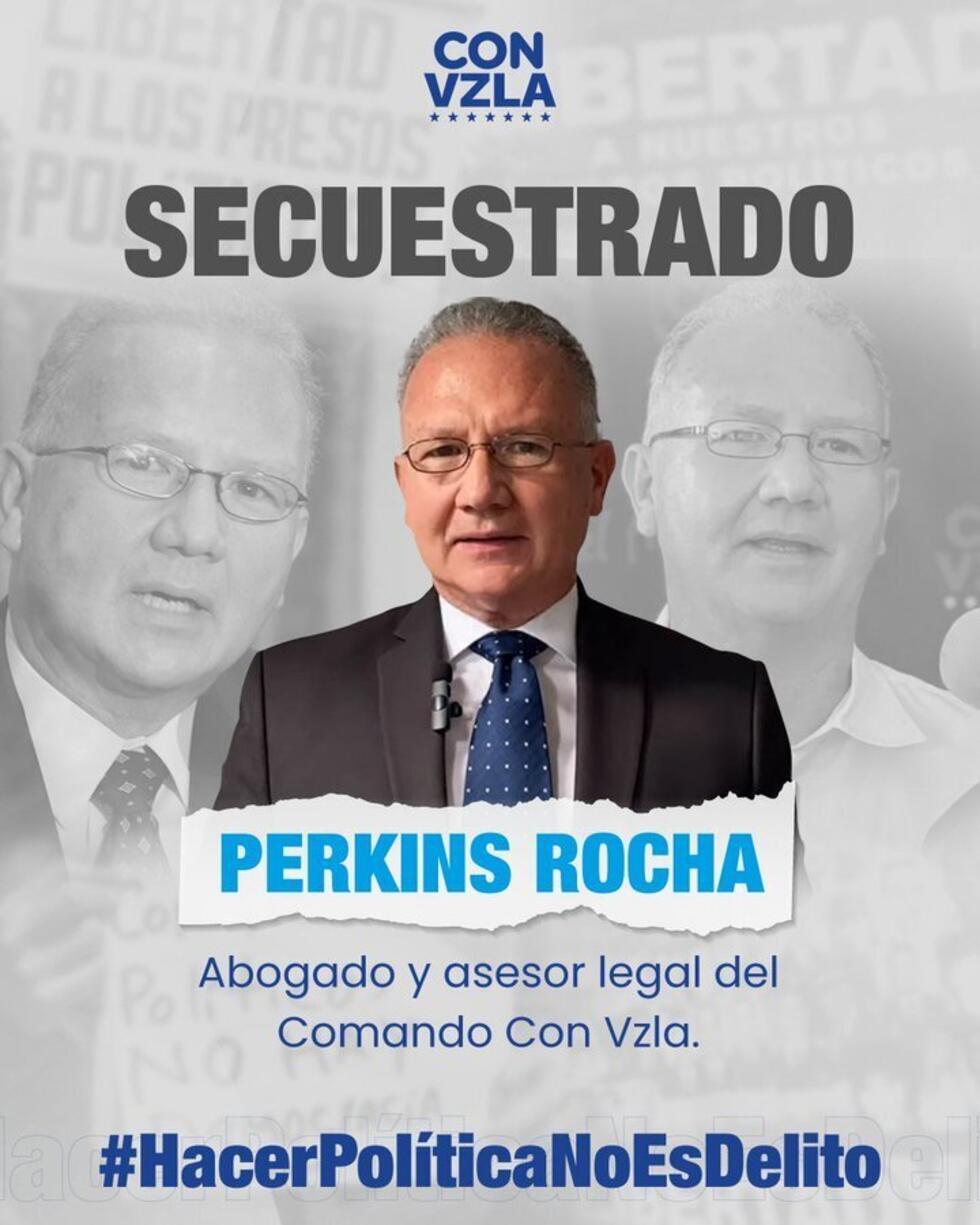

However, hundreds of political prisoners are still behind bars. One of them is Perkins Rocha, the lawyer of opposition figure María Corina Machado, who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2025.

Rocha represented the opposition in the National Electoral Council during the contested presidential election in July 2024. A month later, he was arrested. One UN expert said that his arrest and detention "could be in retaliation for helping opposition candidates during Venezuela’s last election".

Rocha is being held at El Helicoide, a prison in Caracas that the opposition and human rights activists say is a torture centre.

This image was posted on August 27, 2024 by María Corina Machado’s political party Vente Venezuela to denounce the arrest of Perkins Rocha. The slogan translates roughly to "politics isn’t a crime". © X / @VenteVenezuela

This image was posted on August 27, 2024 by María Corina Machado’s political party Vente Venezuela to denounce the arrest of Perkins Rocha. The slogan translates roughly to "politics isn’t a crime". © X / @VenteVenezuela

'When will they call me to tell me that my husband will be released?'

Our team spoke to Rocha’s wife, María Costanza Cipriani. She says that she wasn’t able to visit him in prison until October 2025, more than a year after his arrest.

I don’t understand why he hasn’t been released yet because a lot of people with similar backgrounds have already been able to leave prison. Even if I am very happy for those who have been released, because they are all innocent, it’s really a difficult moment for me. I keep asking myself, "When will they call me to tell me that my husband will be released?"

'We expected a much higher number of releases'

Edward Ocariz is a member of the Comité por la Libertad de los Presos Políticos (Committee for the Liberation of Political Prisoners), a Venezuelan NGO.

Though many political prisoners have been released from prisons recently, largely because of pressure from the international community, we expected a much higher number.

More and more families are daring to speak out about the fact that their loved ones are incarcerated, something that they weren’t doing before, because they were so terrified. So we’ve discovered more than 200 new cases of political prisoners in January alone. There are still around 1,200 people imprisoned for political reasons, according to our estimates. And there are surely more.

The NGO Foro Penal reported in late January that, by their count, 711 political prisoners remained in prison. They also said that new cases had been reported to them in recent weeks.

Ocariz says that, in Venezuela, some citizens have been imprisoned simply because they were "denounced" by those with close links to the regime.

To display this content from X (Twitter), you must enable advertisement tracking and audience measurement.

María Costanza Cipriani, the wife of lawyer Perkins Rocha, explains:

If my husband is freed, I would like him to be freed completely, meaning that he would be at liberty to give interviews, describe what he experienced, leave the country to visit his children, participate in the reconstruction of the country, etc. I say that because the people who have been freed thus far still have not regained their liberty: they may no longer be in prison, which is already an important step, but they were released under strict conditions.

'He can’t speak: he feels gagged'

Carlos Julio Rojas is one person facing the situation that Cipriani described. Rojas is a journalist and coordinator of an association for the residents of north Caracas. He was arrested on April 15, 2024 and was also imprisoned in El Helicoide. He was finally able to leave prison on January 14, but has not regained total liberty – a situation denounced by Amnesty International.

To display this content from X (Twitter), you must enable advertisement tracking and audience measurement.

Rojas is not allowed to speak publicly. So our team spoke to his wife, Francy Fernández Terán, on January 28. Her husband sat next to her during the interview, remaining silent.

His release document states that he is not allowed to leave the country and that he has to report to court every 30 days. Then, the court also stipulated that he is not allowed to speak out or make statements. So he feels gagged.

We want his complete freedom and the end of censorship so that Carlos Julio and other journalists can speak, write, document what happened and speak about what they experienced in prison.

Journalist Carlos Julio Rojas (at left) attended an interview with our team on January 28, 2026, but because of the conditions of his release from prison, only his wife Francy Fernández Terán (at right) could answer our questions. © France 24 Observers

Journalist Carlos Julio Rojas (at left) attended an interview with our team on January 28, 2026, but because of the conditions of his release from prison, only his wife Francy Fernández Terán (at right) could answer our questions. © France 24 Observers

'He spent four months in solitary confinement'

Francy Fernández Terán explains:

Carlos Julio was imprisoned solely because he was defending the rights of the residents of central Caracas when they didn’t have access to water or electricity and because he became a leader who was respected and listened to.

During his detention, he spent four months in solitary confinement. During this period, I had no news from him and I wasn’t allowed to bring him food, clothes or medicine. And his case received media attention. Without that, I think it could have been much worse.

He wasn’t allowed to write in prison and, one day, he said to me, "I’m afraid that when I go home, I won’t know how to write anymore." But he’s already written one article since getting out of prison – a very good article – though, of course, it can’t be published.

'Requiring people to report to court once a month is a way to continue to control them'

Edward Ocariz, from Comité por la Libertad de los Presos Políticos, confirms the restrictions imposed on political prisoners who have been released from prison.

They have all been released under judicial supervision measures. When they are released, they are given a document that says, for example, that they can’t go to protests or meetings and that they have to appear before a judge every month, etc. This violates some of their rights but it is legal: our country’s Code of Penal Procedure clearly lists measures like this. Requiring people to report to court once a month is a way to continue to control them.

However, there is also an illegal element to what the authorities are doing. When the prisoners go before a judge, they are often told that they are not allowed to speak out, that they can’t ask for help from NGOs… They even told some of them that they weren’t allowed to have cell phones. It is a form of intimidation, so that they remain silent.

As a result, it is very hard for us NGOs to record their accounts of what happened, even though it is necessary to document what they experienced in prison so that we can call for justice.

'The main effects are psychological'

The political prisoners who have been released all came out thinner. Many – including young, active people – have health problems that they didn’t have before like cardiopathy [a heart disease] or arterial hypertension. However, the main effects are psychological. Some of them are afraid to leave their homes, out of fear. Others wake up every time they hear a sound and sometimes wake up crying. Some of them are distant with their loved ones. Some feel abandoned because their children left the country while they were in prison.

To display this content from X (Twitter), you must enable advertisement tracking and audience measurement.

Announcement of a general amnesty law

On January 30, Venezuela’s interim president, Delcy Rodriguez, announced that a law of general amnesty, "covering the entire period of political violence between 1999 and today", would be presented to the National Assembly. During the same speech, she announced that El Helicoide would be shut down.

These announcements represent a glimmer of hope for the political prisoners still behind bars and for those who recently left prison but are still not free.

However, NGOs are viewing the announcement of this law with caution. Foro Penal said that any amnesty must not "favour or include those who committed human rights violations or crimes against humanity" and that it was important to ensure that these violations would not be repeated.

"Amnesty implies ‘erasing’ the crimes that were committed," María Costanza Cipriani, Perkins Rocha’s wife, says. "In the case of my husband, the crimes were invented. That said, if this law allows my husband to come home, then I would obviously be very happy."

English (US) ·

English (US) ·