Joel Gunter,senior international reporter, New Brunswickand Nadine Yousif,senior Canada reporter, New Brunswick

BBC

BBC

Five hundred people in a small Canadian province were diagnosed with a mystery brain disease. What would it mean for the patients if the disease was never real?

In early 2019, officials at a hospital in the small Canadian province of New Brunswick noticed that two patients had contracted an extremely rare brain condition known as Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease, or CJD.

CJD is both fatal and potentially contagious, so a group of experts was quickly assembled to investigate. Fortunately for New Brunswick, the disease didn't spread. But the story didn't end there. In fact, it was just beginning.

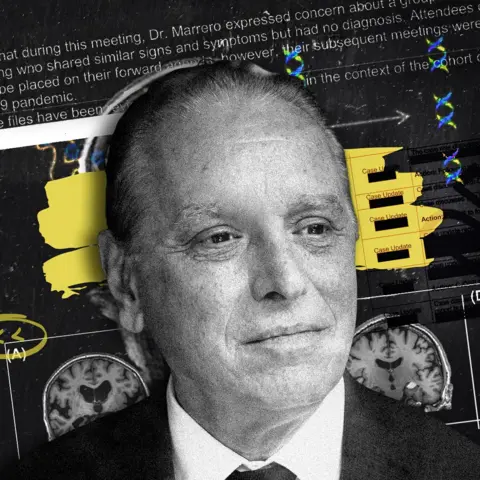

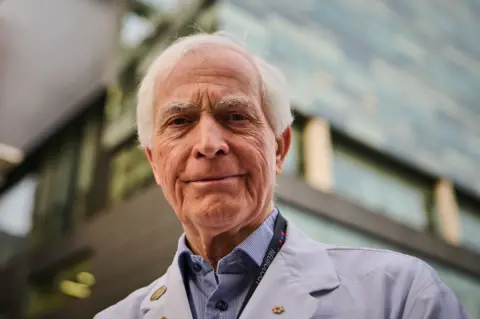

Among the experts was Alier Marrero, a soft-spoken, Cuban-born neurologist who had been working in the province for about six years. Marrero would share some worrying information with the other members of the group. He had been seeing patients with unexplained CJD-like symptoms for several years, he said, including young people who showed signs of a rapidly progressing dementia. The number of cases was already more than 20, Marrero said, and several patients had already died.

Because of the apparent similarity to CJD, Marrero had been reporting these cases to Canada's Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Surveillance System, or CJDSS. But the results had been coming back negative. Marrero was stumped.

More worrying still, he was seeing a dizzying array of symptoms among the patients, according to his notes. There were cases of dementia, weight loss, unsteadiness, jerking movements and facial twitches. There were patients with spasms, visions, limb pain, muscle atrophy, dry skin and hair loss. Many said they were suffering with both insomnia and waking hallucinations. Patients reported excessive sweating and excessive drooling. Several exhibited Capgras Delusion, which causes someone to believe that a person close to them has been replaced by an identical-looking imposter. Others appeared to lose the ability to speak. One patient would report that she had forgotten how to write the letter Q.

Marrero ordered test after test. But he was at a loss. "I just kept seeing new patients, I kept documenting new cases, and I kept seeing new people dying," he recalled. "And an image of a cluster became more clear."

Many of the cluster patients believe industrial poisoning has affected New Brunswick's environment. (Chris Donovan/BBC)

Over the coming months, Marrero and the CJDSS scientists began to suspect that instead of a small cluster of CJD patients, the province of New Brunswick might have on its hands a much larger cluster of people suffering from a completely unknown brain disease.

Over the next five years, Marrero's cluster would balloon from 20 to an astonishing 500. But there came no scientific breakthrough, no new understanding of neurology, no expensive new treatments. Instead, last year, a bombshell research paper authored by several Canadian neurologists and neuroscientists concluded that there was in fact no mystery disease, and that the patients had all likely suffered from previously known neurological, medical, or psychiatric conditions. The New Brunswick cluster was, one of the paper's authors told the BBC, a "house of cards".

To report this story, the BBC spent time with Marrero and spoke to a dozen of his patients or their relatives — some of whom are telling their story for the first time — as well as key scientists, experts, and government officials, and reviewed hundreds of pages of internal emails and documents obtained by freedom of information requests.

We can reveal that at least one cluster patient has now opted for death via medical assistance in dying — legal in Canada since 2016. The diagnosis on the death certificate, according to the doctor who signed it off, was "degenerative neurological condition of unknown cause". At least one other cluster patient is currently considering assisted dying.

The research paper published last year could have marked the end of a strange chapter in Canadian science. Except, hundreds of the patients disagree. Defiant, fiercely loyal to Marrero, and backed by passionate patient advocates, they argue that the paper is flawed and reject any notion that the cluster might not be real.

Many believe instead that they have been poisoned by an industrial environmental toxin, and that the government of New Brunswick has conspired against them to cover it up.

"I'm not a conspiracy theorist type person, at all, but I honestly think it's financially motivated," said Jillian Lucas, one of the patients. "There's all these different levels."

Lucas first met Marrero back in early 2020, after her stepfather, Derek Cuthbertson, an accountant and military veteran, began experiencing cognitive and behavioural problems including sudden rage and loss of empathy. He was referred to Marrero, who ordered a battery of tests but was unable to explain his symptoms. Cuthbertson became one of the early cluster patients — the so-called "original 48".

Lucas had just gone through a divorce and suffered a bad concussion, and she moved back in with her mother and Cuthbertson in their rural community near the city of Moncton. Soon she began experiencing her own symptoms and went to see Marrero for herself.

"He ran so many tests, so much blood work and scans and spinal taps," Lucas recalled. "We were trying to rule absolutely everything out and we just kept coming up with more questions."

Short on answers, Marrero added Lucas to the cluster. Over the coming months, her symptoms worsened and new symptoms appeared. She experienced light sensitivity, tremors, terrible migraines and issues with her memory and ability to speak clearly, she said. She felt unexplained stabbing pains. Cold water felt scalding hot.

Jillian Lucas and her stepfather Derek Cuthbertson. Both were diagnosed by Marrero with the mystery illness. (Chris Donovan/BBC)

Marrero, though, was attentive and caring. He took her symptoms seriously. "He made me feel seen and that what I was experiencing was important," Lucas wrote in a Facebook post about her struggle.

It was a sentiment that seemed to be shared by everyone who saw Marrero. He held their hands during appointments. He remembered them, cried with them. He was "the only one listening to them," said Lori-Ann Roness, one of the cluster patients.

"He's an incredible human and physician," said Melissa Nicholson, whose mother died last year after being diagnosed with the mystery disease.

"Watching our mom go through it was hard enough," Nicholson said. "But he was such a pillar of support."

In March 2021, with Canada still in the grip of the Covid pandemic, the cluster suddenly became news. New Brunswick's chief medical officer had sent a memo to doctors alerting them to the apparent syndrome and suggesting they contact Marrero with possible cases. The memo leaked and the story hit the papers.

Marrero found himself inundated with new patients. But he was also drawing support from the highest levels of Canadian science. The working group set up to respond to the original CJD cases had evolved into a multi-disciplinary group studying the cluster, and the possibility of a mysterious new neurological condition seemed, at times, irresistible to the scientists.

"It's like reading a movie script," emailed one researcher to colleagues, about an early story in the Toronto Star.

"We are all in the movie!", a senior federal scientist replied.

Dr Marrero at home in New Brunswick. "I kept documenting new cases and I kept seeing new people dying," he said. (Chris Donovan/BBC)

At the heart of the working group was Marrero, along with Dr Michael Coulthart, the head of the CJD Surveillance System; Dr Neil Cashman, a leading Canadian neurologist; Dr Michael Strong, the head of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR); and Dr Samuel Weiss, one of the CIHR's senior neurologists. All agreed that Marrero needed considerable support. Strong said he could arrange additional staff and offered himself up as a consultant. The CIHR offered the province of New Brunswick C$5 million ($3.6m; £2.7m) to investigate.

And the mystery disease got a name: the "New Brunswick Neurological Syndrome of Unknown Cause". In an email to Marrero in April 2021, Strong called it "one of the most unusual constellations of findings I have ever seen".

"We all owe you a debt of gratitude," he wrote.

But not everyone was on board. Dr Gerard Jansen, a neuropathologist who was attached to the CJD Surveillance System, had noticed something unusual when referrals from Marrero's office started piling up. Jansen recalled feeling "flabbergasted" at Marrero's notes, which he said featured an array of broad and unrelated clinical observations — a "diarrhea of symptoms".

Jansen saw clues in the patients' files that he said pointed to already defined neurological diseases. When he examined brain tissue samples of a few cluster patients who had died, he found signs of Alzheimer's disease and Lewy body dementia.

He was alarmed. His superior, Coulthart, appeared to believe something unexplained was happening in New Brunswick, Jansen said. Keen to get his concerns down in writing, he sent Coulthart a long and detailed email.

"All available evidence and logic" pointed to a collection of different diseases, Jansen wrote.

"The patients are real, but the clustering as a mystery disease is not."

The early cases seemed to be grouped around two locations: Moncton and the Acadian Peninsula. Suspecting an environmental link, the scientists and officials considered various possible culprits, from a rare moose-borne parasite to blue-green algae blooms to Agent Orange sprayed on the province in the 1970s. Nothing bore fruit.

Marrero said he had observed an uptick in cases in late summer and early autumn — forestry spraying season — and he zeroed in on a controversial herbicide called glyphosate. Chronic exposure to glyphosate, which is used extensively by New Brunswick's forestry industry, has been linked by some studies to neuroinflammation and Parkinson's disease. (Forest NB, an industry body, told the BBC that glyphosate was used in compliance with regulations and was "not expected to pose risks" to human health or the environment.)

According to Marrero, many of his patients were showing highly elevated levels of both glyphosate and various heavy metals. Though when asked by the BBC what proportion of his 500 or so patients had concerning results, he refused to say. "I don't want to provide exact numbers of anything, but let's say it's an unusual number. Beyond 100."

By April 2021, the focus was firmly on a possible environmental toxin. Strong, the CIHR director, said he thought a full "boots-on-the-ground" investigation was needed. The same month, a specialist clinic — the Mind Clinic — was set up in New Brunswick with Marrero at the helm to treat the cluster patients. With the $5m on offer from the CIHR, and the backing of Strong and other top federal scientists, all the conditions appeared set to get to the bottom of the mystery.

But then, everything changed. In May, New Brunswick effectively suspended the collaboration with the federal scientists. The province also decided not to take up the $5m on offer from the CIHR. According to Marrero, the decision killed off any prospect of finding an answer. "Everybody received that email like a cold shower," he said.

None of the provincial officials involved agreed to talk to the BBC on the record. But it is clear there was concern about Marrero's methods and about the nature of his contact with Coulthart, Strong and the other federal scientists. The view of some at senior levels of the New Brunswick government was that the informal working group, seduced by the possibility of a scientific mystery, was circumventing the province.

But the decision to leave the money on the table, rather than spend it investigating, fuelled suspicions that New Brunswick wanted to avoid scrutiny of its environment. According to Kat Lanteigne, the executive director of Canadian health non-profit Bloodwatch and a tireless supporter of Marrero, the actions of the province amounted to a full-blown cover up.

"They pulled the plug because they just don't want anybody looking," Lanteigne said. "Full stop."

Taking control of the process, New Brunswick mounted two investigations into the original cluster of 48 — one telephone questionnaire and one study of the patients' medical records by an oversight committee of six provincial neurologists.

Jansen, the neuropathologist who had raised concerns, had by that point examined the autopsies of eight cluster patients and firmly believed they all had known, diagnosable illnesses. Troubled, he passed his conclusions on to the oversight committee and presented them to the Canadian Association of Neuropathologists.

Not long after that, the New Brunswick government finished its investigations, concluding in February 2022 that there was no common environmental cause and no common condition among the patients. In other words, no mystery disease.

A protest sign in New Brunswick. Some residents are angry about pesticide use in the province. (Chris Donovan/BBC)

But the government had decided against examining any of the patients in person, an omission that outraged those who believed they were part of the cluster. The patients — now 105 in number — were attending sporadic appointments with Marrero at the Mind Clinic but seeing little progress. Jillian Lucas's symptoms were worsening at such a rate that she had begun to weigh something once unthinkable to her: medically assisted dying.

At the clinic, appointments with Marrero could be strangely conspiratorial, patients said. During one appointment, Lucas's stepmother Susan recalled, Marrero put his hand up, told them to stop talking, and went to the door to listen. "He said, 'I believe we are being recorded'."

Stacie Quigley-Cormier, whose stepdaughter Gabrielle was the youngest member of the cluster, said Marrero always spoke in a hushed tone.

"The experience with Dr Marrero — and other patients talk about this too — is you make sure you start talking after the door is closed, and there's a quiet tone to his voice, and you make sure you're not talking in the hallways and things like that."

Marrero declined to discuss it. "Some patients actually thought that way. And I… We wondered… But I don't want to comment."

In August 2022, Marrero was sacked from the Mind Clinic. "Despite our repeated attempts to inform you of our expectations and the deficiencies in your performance, you have not demonstrated a sustained ability to meet our expectations," wrote John Dornan, then-CEO of the health network. The 105 cluster patients each received their own letter, telling them they could stay at the clinic, with all the resources it had to offer, or strike out alone with Marrero.

Many were offended on behalf of their neurologist. "When they called me to ask my choice, I said, it's not a choice, it's an ultimatum," Lucas said. "And I choose him."

Jillian Lucas at home with one of the family's 15 parrots. (Chris Donovan/BBC)

She wasn't alone. Of the 105 patients, 94 chose Marrero. Just 11 people decided to stay with the clinic and get a second opinion.

Outside of the clinic, increasingly isolated, Marrero continued to diagnose the mystery disease. He was sending patients for so many tests, for such obscure toxins or conditions, that some reported being met with an increasingly quizzical eye at the testing clinic, as if to say, "What now?"

Others found it difficult to get an appointment with Marrero or even speak to his assistant.

"I've messaged a couple of times but they're so busy, you can't even hardly get a hold of them by email," said Lucas. "He just has so many patients."

As the cluster generated more news coverage in Canada, little attention was paid to the 11 patients who had decided to stay with the Mind Clinic, and their stories have never been told.

Kevin Strickland's partner April was referred to Marrero after she stopped her car in the middle of the road one morning and apparently forgot how to drive. April, then 60, had already been showing some dementia-like symptoms, but the driving incident scared Strickland. Marrero ran a series of tests on April and diagnosed the mystery illness.

"He told me it was the mystery illness and he wanted to look further into it, but he never really did much after that," Strickland said.

Kevin Strickland at home with his rescue dog. His partner April was diagnosed by Marrero with the mystery illness. (Chris Donovan/BBC)

The couple waited eight months to get important test results from Marrero, Strickland said, as April's condition worsened. Soon Strickland could no longer manage her care. But to get her a place in assisted living he needed a letter of support from Marrero. "I think I waited four months for that letter," Strickland recalled. "I kept phoning and asking."

Eventually he gave up and turned to the Mind Clinic, he said, and got the letter. And the Mind Clinic neurologists gave April something else she needed — a firm diagnosis. She was suffering from a form of frontotemporal dementia. In the end, Marrero "did nothing for April," Strickland said. "I guess he was more interested in proving the mystery illness than he was helping his patients," he said.

Sandi Partridge also chose to remain with the Mind Clinic. She felt a deep sense of loyalty to Marrero, but she also saw simple common sense in getting a second opinion.

Partridge had first seen Marrero in 2020, after suffering headaches and balance issues. He ordered a barrage of tests — according to Partridge she had two MRIs, two EEGs, a SPECT, a CAT scan and a spinal tap, as well as more than a dozen different antibody tests. "It was mostly a lot of testing with Dr Marrero," she recalled. "Every time he would see me, it would be an hour and a half, sometimes two hours, and he would retest me every single time."

But every test came back negative. Partridge had also provided Marrero with a video of her having a seizure at home, which he studied. He diagnosed her with the mystery illness. "Those were the words he used," she said.

Sandi Partridge in a park near her home. "It was mostly a lot of testing with Dr Marrero," she said. (Chris Donovan/BBC)

One thing Marrero never mentioned to Partridge was functional neurological disorder, which was her eventual diagnosis. FND is a complex condition; previously known as psychosomatic or psychogenic illness, it describes physical symptoms with a psychological root. It presents a challenge to doctors, who have to guide patients through the stigma associated with it to an understanding that they have a real condition that requires complex treatment.

Partridge's neurologists at the Mind Clinic also reviewed the seizure video she had shown to Marrero. "As soon as Dr Abdellah saw my seizure he said, that's FND," Partridge recalled. (Abdellah declined to speak to the BBC). Partridge threw herself into researching the condition. "And I thought, that's me, that's me, that's me, that's me," she said. "I hit every single marker."

Partridge is now on a multi-faceted FND treatment programme involving neurology, neuropsychology and occupational health. And she is at peace with her diagnosis. "The stigma is difficult," she said, "but I've accepted it."

Gabrielle Cormier, the youngest patient in Marrero's cluster, would also receive a diagnosis of FND, but her journey would follow a different path.

Cormier has featured heavily in the media coverage of the cluster, becoming a kind of poster child for the mystery disease. She was first referred to Marrero at just 18. A high school student, dancer and competitive figure skater, she had begun to experience fatigue-like symptoms and muscle soreness and then passed out at school.

Cormier was already taking anti-anxiety medication, and the hospital emergency room doctor told her the incident was anxiety-induced. Unhappy with his assessment (he told Cormier, who is gay, that she "just needed to find a boyfriend", she said), the family looked to Marrero for answers.

Gabrielle Cormier was diagnosed by Marrero at just 18. "I've done nothing with my life since I got sick," she said. (Chris Donovan/BBC)

Marrero was different — empathetic, caring. As he had with other patients, he ran Cormier through a gauntlet of tests. When nothing showed up, he diagnosed her with the mystery illness. Canada was deep in the isolation of the Covid lockdown, but Marrero reassured them.

"He said, there's a dozen other people at least that are experiencing similar things to what you're experiencing, and I don't have answers for it yet," stepmother Stacie Quigley-Cormier recalled. "He told her that she wasn't alone."

There was one test Marrero couldn't secure: a PET scan, because the hard-up province was largely reserving them for cancer patients. So Cormier's parents took her to Toronto for the scan and a second opinion by a leading neurologist there, Dr Anthony Lang.

After a multi-day evaluation at a specialist neurology centre, Lang diagnosed Cormier with FND. Her tests showed that conscious movements were weak but forced reflex or automotive movements were normal and healthy. It pointed to psychology.

The Quigley-Cormiers were initially prepared to accept the FND diagnosis, they said. But they left Toronto unhappy after Lang told them to stop treating Cormier as though she had a terminal illness because it was reinforcing her condition.

A few weeks later, Lang called Cormier to inform her that a delayed test result had shown some reduced blood flow in her brain — something Marrero had also observed — and which can be caused by various medical or psychological issues including depression. Lang told Cormier the abnormality was slight and bore no relation to her symptoms, so she shouldn't worry about it.

The call didn't sit well with the Quigley-Cormiers.

"There was no reason to call her personal phone when he knew she had memory problems," said her father Andre, angrily.

Global News

Global News

Gabrielle Cormier, in her wheelchair, with other patients calling for suppport. Jillian Lucas is far left. (Global News)

The call pushed the Quigley-Cormier family away from Lang and his FND diagnosis and back towards Marrero, who the family had come to believe in deeply. Marrero had never crossed "any kind of line," Stacie said. "He's pristine."

"That's why all his patients like him," Andre said. "Love him, maybe."

Marrero continued to test Cormier repeatedly. He prescribed anti-seizure medication to prevent possible seizures, though she had not had any. He referred her for a round of intravenous immunoglobulin treatment — which she said caused severe headaches, aches, nausea, dizziness and aseptic meningitis — and prescribed a powerful intravenous immunosuppressant used for blood cancers and autoimmune illnesses. Neither improved her condition.

Cormier once dreamed of studying pathology. But her illness caused her to drop out of university and for years she has gone everywhere either in a wheelchair or with a cane, living, for a 24-year-old, a restricted life.

"I've had this idea that my life has been wasted, or that I've done nothing with my life since I got sick," she said.

"So, yeah, it kind of feels like I've been robbed of that."

Lang, the Toronto neurologist, came away from his interaction with the Quigley-Cormier family troubled. His call to Cormier was not only appropriate, he said, he was ethically bound to communicate with her directly because she was a mentally competent adult who did not ask for her parents to act for her.

Over the coming months, Lang watched with concern as the purported cluster ballooned in New Brunswick. He emailed Marrero and left messages with his secretary offering help, but never heard back. In late 2023, frustrated by what he saw as cluster misinformation everywhere, Lang decided with colleagues to mount a study. The results — published in May 2025 in the Journal of the American Medical Association, JAMA — landed in New Brunswick like a hand grenade.

Lang and his co-authors — including several former Mind Clinic colleagues of Marrero and the concerned neuropathologist, Gerard Jansen — found that all 25 patients in their study had suffered from previously known conditions, from functional neurological disorder to dementia to cancer. The probability of there being no new disease was close to 100%, they said. The real cause of the cluster, they concluded, was serial misdiagnosis by Marrero, compounded by credulous media reporting, the limitations of New Brunswick's public health system, institutional distrust sown by the pandemic and the actions of a small group of people "co-opting the crisis to suit their agenda".

Dr Lang was the leading author on a paper casting doubt on the cluster. (Sammy Kogan/BBC)

The cases in the JAMA paper consisted of 14 live patients and 11 autopsies. Most of the live patients were people who had chosen to remain at the Mind Clinic, like Sandi Partridge. A few, including Gabrielle Cormier, were included via a consent waiver — a legal process which allows researchers to use patient data without their express consent provided certain anonymity criteria are met.

The study's conclusions incensed the most vocal patients and patient advocates, including Kat Lanteigne and Stacie Quigley-Cormier, who allege that the research was unscientific and unethical. The Quigley-Cormiers are furious that Gabrielle's data was used for the study, and their lawyers have sent letters to Lang and to the journal alleging the paper was a violation of her privacy. JAMA declined to comment on the dispute. Lang said that the research was legal, ethical and appropriately anonymised. As for the alleged violation of privacy, he pointed out that the only reason anyone knew Cormier's data was used was because her father and stepmother had told the media, along with many other details about her life.

On a bright morning this past September, Marrero was sitting in his home office in a large cottage-style house on a plot of land just outside of Moncton. A stone fountain burbled softly in his Japanese-inspired peace garden. Birds sang in his own patch of forest — untouched by herbicides or pesticides, he said.

Marrero is undeniably charismatic. He has a warm smile and demeanour. He speaks gently, but with authority. He remembers small details about people he barely knows and asks about their wellbeing in a manner that conveys genuine care.

Settled in his office chair, he recalled with obvious pleasure that not so long ago, some of Canada's top scientists had sat with him around that very desk, ready to take on a scientific mystery. But now, Marrero seemed increasingly isolated.

"They are trying to present me as it," he said, dejectedly. "I was part of it, but I was not it. The only difference is, when the table was empty, I stayed."

Of Marrero's early federal collaborators — Drs Coulthart, Cashman, Strong, and Weiss — only Coulthart agreed to speak to the BBC about the cluster. He denied ever having been convinced by the idea of a unified, mystery syndrome. "As a scientist, I use the word convinced very, very sparingly," he said. "But don't let anybody kid you — if anyone says they know what's going on or isn't going on in New Brunswick, they're either lying or grossly mistaken. Because nobody has the facts."

Dr Marrero in his home office. "I was part of it, but I was not it," he said. (Chris Donovan/BBC)

An upcoming provincial report could offer some answers. Unlike the previous studies, it will examine the claims of elevated glyphosate and heavy metals in the patients. At times, the stakes seem impossibly high. "Lives hang in the balance," read a recent letter to Premier Susan Holt, signed by 72 of the patients. "It is within your power to honour them, cherish them, and care for them," the letter said. "Or you can abandon them and let them wither, fade, and ultimately die. Please join us on the right side of history."

The patient advocates, led by Bloodwatch director Kat Lanteigne, have arguably done more than anyone to keep the story of the cluster going, with an operation that includes lobbying the government, briefing the press and sending legal letters to scientists.

Lanteigne has publicly attacked both Jansen and Lang over the JAMA study, branding their work inaccurate and unethical. She denied harassing Jansen, saying she had never spoken to him directly and emailed him only once. "I have a record of speaking truth to power and I have always worked with integrity and honesty," she said.

Both Lang and Jansen are standing their ground.

"What we have here is a case of misdiagnosis, evolving to misinformation, and sadly resulting in suffering for patients and families," Lang said.

"I would even go further," Jansen said, regarding the alleged misdiagnosis of the patients. "I would say they are being abused."

Few others are willing to criticise Marrero so openly. Privately, former senior government officials and colleagues of Marrero have questioned whether he should have been investigated. The Royal College of Physicians told the BBC it could not comment on whether there had been complaints against any individual physician, and none have been made public in relation to Marrero. Any sanction process would typically begin with a complaint.

And that was the issue, one former senior health official said.

"It has to be a patient complaint," they said. "And all his patients love him."

The last time Jillian Lucas saw Marrero was more than a year ago. He tested her again, but she is yet to see the results. During the appointment, he told her that just getting a common cold could kill her, she said. So she rarely leaves the house — a cramped and densely cluttered property that the family shares with 15 parrots. "She spends 90% of her time in her bedroom," her stepmother said. "It's a very limited life."

Kat Lanteigne told the BBC that Marrero "deserves the Order of Canada for what he has done for these people." But many patients, like Lucas, are languishing. Largely untreated, they have undergone test after test in search of the mystery disease and ended up back where they began, or somewhere worse.

In response to criticisms in this story, Marrero said that he would not comment on patients or fellow physicians. "The focus must remain on the hundreds of suffering patients, their families and communities who need to be the heart of our attention and care," he said.

Jillian Lucas in her back garden. "I don't want to be in a nursing home, or be a burden," she said. (Chris Donovan/BBC)

Jillian Lucas has now seen a second doctor, but only because she has pushed ahead with her decision to explore medical assistance in dying, which requires two physicians to sign off. Canada has among the world's most permissive laws for assisted dying, allowing people to pursue it without a terminal diagnosis.

When Lucas told Marrero her plan, he became "choked up", she said. "It eats him up, he's fighting back tears."

And yet, Marrero agreed to support her application, despite her not having a concrete diagnosis or testing positive for any known condition. (Marrero told the BBC he "took the utmost care to abide by" the laws around Maid and had "never proposed it" to a patient.) After all the years of uncertainty with the unknown neurological syndrome, the option of dying gave Lucas some sense of control. "I have a limit in my mind of how far I can go," she said.

Sitting in his garden office, the sun streaming in, Marrero had no such limits in mind. "I keep going because I know," he said, confidently. He had been able to meet "with some of the best scientists in the country," he said. He had more than 500 cluster patients now, and every week the number was going up.

1 month ago

21

1 month ago

21

English (US) ·

English (US) ·