February 9 was a date that haunted Robert Badinter throughout his life – until his death on February 9, 2024, at the age of 95.

On that same day in 1943, his life was turned upside down. “February 9 is the day of the roundup on Rue Sainte-Catherine in Lyon, during which his father, Simon Badinter, was arrested on the orders of Klaus Barbie,” says Alain Jakubowicz, a lawyer and former president of the International League Against Racism and Anti-Semitism (LICRA).

Born into a Jewish family originally from Bessarabia, a region now located in Moldova, Badinter grew up in Paris. But by the start of 1943, Robert, his brother and their parents were in Lyon, having fled the northern part of France occupied by Nazi forces for fear of arrest.

When German troops invaded the “free zone” governed by the Nazi-era Vichy government in November 1942, the family faced an even greater threat.

SS officer Klaus Barbie, who became known as the “Butcher of Lyon”, was named head of the local Gestapo and launched a mass roundup of Jews.

The original wound

On February 9, 1943, Simon Badinter went to Rue Sainte-Catherine to the Union Générale des Israélites de France (General Union of French Israelites), an institution created by the Vichy government to represent Jews in their dealings with public authorities. A dozen plainclothes police stormed the building, arresting 86 people, including Robert's father. “When Robert's mother didn't see her husband come home, she asked her son to go and see what was happening,” says Jakubowicz, who was a lawyer for the plaintiffs in the Barbie trial in 1987.

“The Nazis were waiting for people to arrive so they could arrest them. Robert entered the building, but managed to escape. It is impossible to understand the man in all his complexity without grasping what happened that day,” says Jakubowicz.

Badinter did not return to the scene of his father’s arrest until 2006, explains Jakubowicz. The annual ceremony commemorating the roundup “always takes place on the street, outside, but he wanted to go inside the building. He climbed the steps alone and put a kippah on his head. He had flashes of recollection that were almost mystical.”

For Dominique Missika, co-author of Robert Badinter, l’homme juste (Robert Badinter, the Just Man), the day of his father’s disappearance was particularly “distressing” for the son.

“That day, February 9,1943, was one of loss,” says Missika, a historian who specialises in World War II, adding that Badinter never got over it. “He always tried to remember whether he had caught his father's eye on Rue Sainte-Catherine on the day of the arrest,” Missika says.

Robert Badinter, then 14 years old, would never see his beloved father again. Transferred to the Drancy internment camp outside Paris, his father was deported on Convoy 53 to the Sobibor camp in Poland, where he was murdered. Pursued by the Gestapo, the Badinter family found refuge in the village of Cognin, near Chambéry in Savoie.

Until the end of the war, Badinter attended school there under the name of Berthet.

“In 1994, he returned [to Cognin] during the trial of Paul Touvier,” responsible for the execution of Jewish hostages in June 1944 and the first French citizen to be convicted of crimes against humanity committed during the Vichy regime.

Badinter “wanted to tell the children of the village that their grandparents had been good people and that they had nothing to do with this Vichy militia member”, Missika says.

The Barbie trial

Back in Paris after the war, Robert waited for his father’s return, hoping to find him at the Hotel Lutetia in Paris, a luxury hotel requisitioned by the French government to welcome concentration camp survivors.

When Hotel Lutetia welcomed concentration camp survivors

To display this content from YouTube, you must enable advertisement tracking and audience measurement.

One of your browser extensions seems to be blocking the video player from loading. To watch this content, you may need to disable it on this site.

06:07

Naftoul, his maternal uncle, and Shindléa, his paternal grandmother, had both been deported to Auschwitz.

His mother was waging a battle in court to recover their flat, which had been taken over by someone else.

During an April 1945 hearing in the case, the Badinters’ lawyer stated that the flat’s owner, Simon Badinter, was “still in a concentration camp”.

Robert Badinter was present at the hearing to hear the judge's scathing response: “That detail is of no interest to the court.”

France, which had only just been liberated from the Nazis, was not preoccupied by the fate of its Jewish population.

Badinter resumed his studies with a heavy heart. He quickly turned to law and became a solicitor, first specialising in business law and then criminal law. He became known for his opposition to capital punishment.

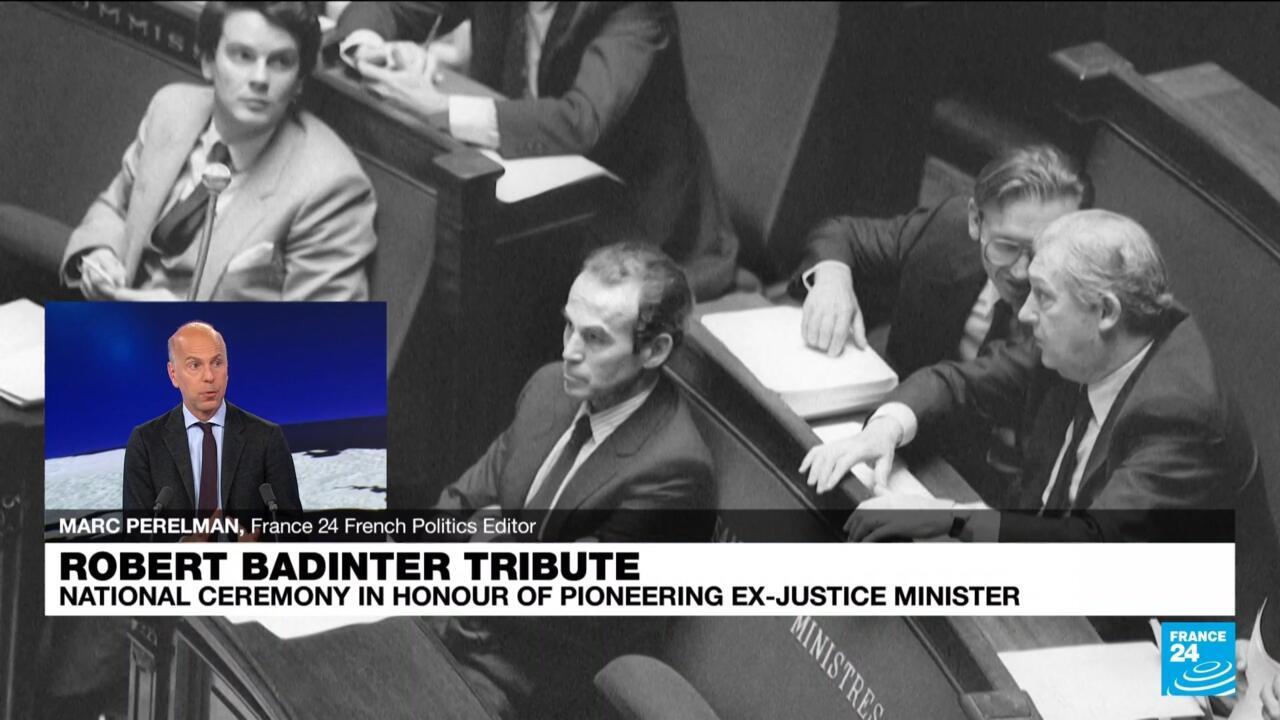

Read moreFrance pays tribute to Badinter, ex-justice minister who fought to abolish death penalty

He joined the government of then Socialist president François Mitterrand as minister of justice in 1981 and introduced a bill to abolish the death penalty.

Upon joining the ministry, his first thought was of his father.

“His father, who was naturalised in 1928, raised him to love the Republic and France,” says Missika. “Imagine this immigrant son finding himself in the gilded halls of the Republic.”

His family’s wartime history came up again during his time as minister. Barbie, who had been hiding in South America under the name Klaus Altmann, was arrested in Bolivia in 1983 and extradited to France.

Badinter “was the one who requested that Klaus Barbie be imprisoned at Fort Montluc, the very place where he had tortured so many people”, says Jakubowicz.

“He was minister of justice at the time when the person responsible for his father's death was about to be tried. It was incredible,” Missika notes.

Barbie was tried in 1987. Badinter kept his distance from the proceedings to avoid being accused of bias and was not one of the plaintiffs in the case.

‘You will always be falsifiers of history’

Badinter fought against anti-Semitism throughout his life. In court, he faced Holocaust denier Robert Faurisson on several occasions. In 1981, he had him convicted for stating that “Hitler never ordered nor permitted that anyone be killed by reason of his race or religion”.

The two men faced off again in 2007. Faurisson sued Badinter for calling him a falsifier of history. With characteristic fervour, Badinter declared from the witness stand: "Holocaust denial is one of the worst acts of historical falsification. It would be as if, all of a sudden, there had been no deaths, no murderers, that the Jews who died had died for nothing, died by chance. For me, until the end of my days, until my last breath, I will fight against you and those like you. You will always be falsifiers of history." Faurisson's case was dismissed.

Robert Badinter: 'One of the giants' of French politics

To display this content from YouTube, you must enable advertisement tracking and audience measurement.

One of your browser extensions seems to be blocking the video player from loading. To watch this content, you may need to disable it on this site.

03:05

While a senator for the Hauts-de-Seine region west of Paris in 1997, Badinter initiated a project to erect a monument to those executed by the Germans at Mont-Valérien, many of whom were Jewish resistance fighters. A bronze bell bearing their names was unveiled in 2003.

Unwavering friendship with Mitterrand

Badinter’s public stances were not always easily understood. Some criticised his unwavering support for Mitterrand. On July 16, 1992, he defended the French president during a ceremony marking the 50th anniversary of the Vélodrome d'Hiver roundup, during which nearly 13,000 Jews were arrested in and around Paris.

Mitterrand, who had refused to acknowledge the responsibility of the French state in the arrests and declared a few days earlier that the Vichy regime “was not the Republic”, was booed by part of the audience. Badinter – then president of the Constitutional Council, France’s highest court – stood at the podium and shouted, “You make me feel ashamed!”

Following revelations about Mitterrand’s friendship with René Bousquet, the former secretary general to the Vichy police and organiser of the Vélodrome d'Hiver roundup, Badinter remained silent. He merely acknowledged that he had sent the president a letter on the subject.

“We tried in vain to ask him what he had written to Mitterrand,” says Missika. “He said that Mitterrand was a friend and that he would not betray him. I think it was extremely painful for him to learn this, but he preferred to keep his feelings to himself. It will remain between them. That's consistent with his character.”

Faithful in friendship, Badinter was also faithful to his work. He aroused anger in the Jewish community in 2001 when he argued that Maurice Papon, convicted of complicity in crimes against humanity for the arrest and deportation of Jews in the Gironde region during the war, should be released after 15 months imprisonment due to his advanced age.

Robert Badinter: Abolition of death penalty

To display this content from YouTube, you must enable advertisement tracking and audience measurement.

One of your browser extensions seems to be blocking the video player from loading. To watch this content, you may need to disable it on this site.

00:35

“This was a continuation of his fight against the death penalty,” says Jakubowicz. “For him, a human being can commit monstrous acts, but the human dimension must always prevail.”

Badinter continued to defend his vision of justice and to combat anti-Semitism until his last breath. When France was hit by a wave of terrorist attacks, he spoke out publicly against “this centuries-old evil”.

Deeply scarred by a 2012 attack on a Jewish school in Toulouse, Badinter spoke at UNESCO four years later. “One image haunts my mind: a man chasing Jewish children in a Jewish school, a little girl running away. And because she is running away, this man grabs her by the hair and shoots her at point-blank range. What is this crime, if not a repeat of the actions of the SS?”

Sadly, he passed away at a time when France is experiencing a sharp rise in anti-Semitic attacks, with 1,570 such acts recorded in 2024.

"He obviously found it very difficult to cope with. He was truly in love with France. He could not accept this anti-Semitic France," says Jakubowicz.

According to Jakubowicz, such public figures are now rare: “We no longer have great intellectuals who are broad-minded and steadfast in their convictions. Robert Badinter is missed by society. I miss him.”

This article has been translated from the original in French.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·