In the shade of a tarpaulin by the side of the road, three young women are seated at a table in front of a pile of envelopes that contain voter cards for the Ivorian presidential election on October 25.

There was little demand for the cards on Wednesday in Yopougon, a working-class district of 1.5 million inhabitants in western Abidjan, the city’s largest and most populous commune. Wednesday was supposed to be the last day to collect a voter card required to cast a ballot in the poll – though authorities later in the day relaxed the deadline to allow people to collect their voter cards on polling day.

The lack of a queue to get a voter card has various explanations says Anne, a representative of the Independent Electoral Commission (CEI), the body responsible for organising elections.

“Some people don’t come because they don’t feel they need to. Others say they haven’t been informed,” she says. “And then, you know, Yopougon’s nickname is ‘Gbagbo’s Yopougon’. So we assume that’s why people aren’t coming to get their cards, since Yopougon, for the most part, is a stronghold of the opposition.”

Though seen as a bastion of supporters of former president Laurent Gbagbo, Yopougon has elected as head of the town hall a member of President Alassane Ouattara party, the Rally of Houphouëtists for Democracy and Peace (RHDP), since 2013.

Ouattara, 83, was elected president in 2010 and re-elected in 2015 and 2020. His bid for a fourth term in office has been called undemocratic by his opponents, even though his candidacy is allowed by the constitution.

Read moreIvory Coast opposition slams protest ban ahead of controversial presidential poll

‘It's peace we're interested in, not politics’

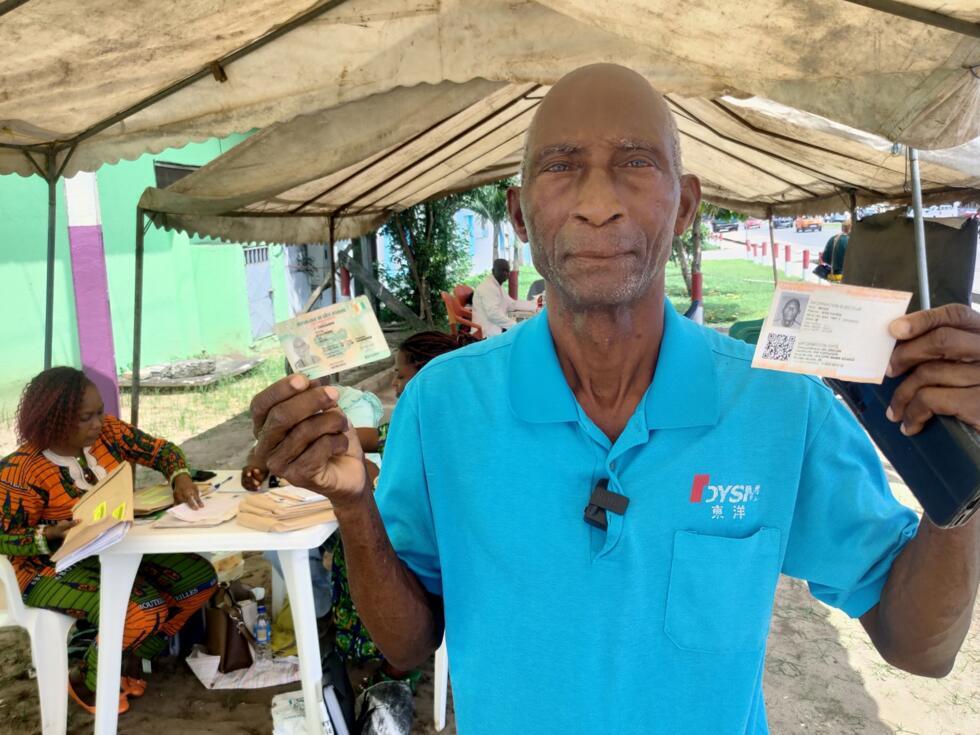

The slender Pierre Mosis N'da presents his ID to collect his voter card. The septuagenarian knows who he is going to vote for but insists on keeping it a secret. “That's between me and myself,” he says.

This former driving school director is primarily concerned about the cost of living. “It's true, we have enough roads, but travelling is expensive because fuel is expensive,” he says.

Pierre Mosis says he “votes regularly” because he feels strongly about fulfilling “his civic duty”. But not everyone in the neighbourhood shares this view. A few metres from the voter registration table, a group of young people are engaged in a discussion. None of them have a voter card.

“I've never voted. I don't know how things work, I'm not interested in politics,” says Charles. “It's peace that interests us. Because anyone who's interested in politics is also ready for a fight,” he says, under the approving gaze of his friends.

“When we talk about elections, everyone is afraid,” adds another young resident of Yopougon, recalling the painful memory of the post-election violence in 2011 between supporters of Gbagbo and Ouattara, which left some 3,000 people dead across the country. “It was horrific, it wasn't easy, not easy ... but thank God we survived, we're still here,” he says, visibly moved.

Pierre Mosis listens, impassive. “There is little enthusiasm for voting because people are wary,” he explains, adding that residents are stocking up on supplies and staying indoors, and sometimes even leaving town during this sensitive period for fear of unrest. “There are people here who are very angry about Ouattara's fourth term; they say he has no right to it,” he adds.

Simone Ehivet waiting in the wings

Though Yopougon’s municipal council is now controlled by the ruling RHDP party, Gbagbo remains very popular there. Since Gbagbo was excluded from standing in the presidential election due to a 2018 criminal conviction, several opposition candidates have been trying to win over his supporters, including his ex-wife and adviser Simone Ehivet.

Read moreIvory Coast’s former first lady Simone Ehivet eyes the presidency

On Wednesday, the former first lady organised a campaign event in a neighbourhood of Yopougon where supporters of her party, the Movement of Capable Generations (MGC), celebrated her arrival with fanfare, blasting music from brass and percussion instruments. “Yopougon is joy,” chanted activists, referring to the festive reputation of the district, which also faces significant economic and social challenges.

André, a 24-year-old activist, came to support Ehivet. “I hope that Ivorians will turn out en masse to make Simone Ehivet the first female president of the Ivory Coast and even of West Africa,” he says enthusiastically.

The young man says he is very attached to Laurent Gbagbo, “the founding father”. “But if Ivorian law stipulates that he cannot be a candidate, we must choose someone else.” In the Ivory Coast, “people pay attention to individuals too much, when it is political ideologies we should be paying attention to,” the young man says.

Like many Ivorians, André says reconciliation should be an absolute priority: “We must restore love and peace to Ivory Coast.” But unlike those who do not believe in politics, he thinks he has the solution. “Simone can do it,” he concludes.

This article has been adapted from the original in French.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·