Goktay Koraltan/BBC

Goktay Koraltan/BBC

Wives and children of suspected Islamic State group fighters are detained in tented camps

In the complex mosaic of the new Syria, the old battle against the group calling itself Islamic State (IS) continues in the Kurdish-controlled north-east. It's a conflict that has slipped from the headlines - with bigger wars elsewhere.

But Kurdish counter-terrorism officials have told the BBC that IS cells in Syria are regrouping and increasing their attacks.

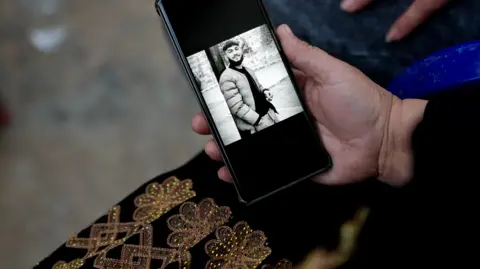

Walid Abdul-Basit Sheikh Mousa was obsessed with motorbikes and finally managed to buy one in January.

The 21-year-old only had a few weeks to enjoy it. He was killed in February fighting against IS in north-eastern Syria.

Walid was so keen to take on the extremists that he ran away from home, aged 15, to join the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). They brought him back because he was a minor, but accepted him three years later.

Generations of his extended family gathered in the yard of their home in the city of Qamishli to tell us about his short life.

"I see him everywhere," said his mother, Rojin Mohammed. "He left me with so many memories. He was very caring and affectionate."

Walid was one of eight children, and the youngest of the boys. He could always get around his mum.

"When he wanted something, he would come and kiss me," she recalls. "And say 'can you give me money so I can buy cigarettes?'"

The young fighter was killed during days of battle near a strategic dam - his body found by his cousin who searched the front lines. Through tears, his mother calls for revenge against IS.

Goktay Koraltan/BBC

Goktay Koraltan/BBC

Walid was killed in February fighting against the Islamic State Group in north-eastern Syria

"They broke our hearts," she says. "We buried so many of our young. May Daesh (IS) be wiped out completely," she says. "I hope not one of them is left."

Instead, the Islamic State Group is recruiting and reorganising - according to Kurdish officials, taking advantage of a security vacuum after the ousting of Syria's long-time dictator Bashar al-Assad last December.

"There's been a 10-fold increase in their attacks," says Siyamend Ali, a spokesman for the People's Protection Units (YPG) - a Kurdish militia, which has been fighting IS for over a decade, and is the backbone of the SDF.

Goktay Koraltan/BBC

Goktay Koraltan/BBC

"I see him everywhere," says Walid's mother, Rojin Mohammed

"They benefited from the chaos and got a lot of weapons from warehouses and depots (of the old regime)."

He says the militants have expanded their areas of operation and methods of attack. They have graduated from hit-and-run operations to attacking checkpoints and planting landmines.

His office walls are lined with photos of YPG members killed by IS.

For the US, the YPG militia is a valued ally in the fight against the extremists. For Turkey, it is a terrorist group.

In the past year, 30 YPG fighters have been killed in operations against IS, according to Mr Ali, and 95 IS militants have been captured.

Kurdish authorities have their hands - and jails - full with suspected IS fighters. Around 8,000 - from 48 countries including the UK, the US, Russia and Australia - have been held for years in a network of prisons in the north east.

Whatever their guilt - or innocence - they have not been tried or convicted.

The largest jail for IS suspects is al-Sina in the city of Al Hasakah - ringed by high walls, and watch towers.

Through a small hatch in a cell door, we get a glimpse of men who once brought terror to around a third of Syria and Iraq.

Detainees in brown uniforms - with shaven heads - sit silent and motionless on thin mattresses, on opposite sides of a cell. They appear thin, weak and vanquished, like the "caliphate" they proclaimed in 2014. Prison officials say these men were with IS until its last stand in the Syrian town of Baghouz in March 2019.

Goktay Koraltan/BBC

Goktay Koraltan/BBC

Al-Sina, located in the city of Hasaka, is the largest jail for IS suspects

Some detainees wear disposable masks to prevent the spread of infection. Tuberculosis is their companion in al-Sina, where they are being held indefinitely.

There's no TV or radio, no internet or phone, and no knowledge that Assad was toppled by the former Islamist militant, Ahmed al-Sharaa. At least that's what the prison authorities hope.

But IS is rebuilding itself behind bars, according to a prison commander who cannot be identified for security reasons. He says each wing of the prison has an emir, or leader, who issues fatwas - rulings on points of Islamic law.

"The leaders still have influence," he said. "And give orders and Sharia lessons."

One of the detainees, Hamza Parvez from London, agreed to speak to us with prison guards listening in.

The former trainee accountant admits becoming an IS fighter in early 2014 at the age of 21. It cost him his citizenship. When challenged about IS atrocities including beheadings, he says a lot of "unfortunate" things happened.

"A lot of stuff happened that I don't agree with," he said. "And there was some stuff that I did agree with. I wasn't in charge. I was a normal soldier."

He says his life is now at risk. "I'm on my deathbed... in a room full of tuberculosis," he said. "At any moment I could die."

Goktay Koraltan/BBC

Goktay Koraltan/BBC

Hamza Parvez, from London, admits he became an IS fighter at 21

After years in jail, Parvez is pleading to be returned to the UK.

"Me and the rest of the British citizens who are here in the prison, we don't wish any harm," he said. "We did what we did, yes. We did come. We did join the Islamic State. It's not something that we can hide."

I ask how people can accept he is no longer a threat.

"They are going to have to take my word for it," he says with a laugh.

"It's something that I can't convince people about. It's a huge risk that they will have to take to bring us back. It's true."

Britain, like many countries, is in no hurry to do that.

So the Kurds are left holding the fighters and about 34,000 of their family members.

The wives and children are arbitrarily detained in sprawling desolate tented camps that amount to open-air prisons. Human rights groups say this is collective punishment - a war crime.

Roj camp sits on the edge of the Syrian desert - whipped by the wind, and scorched by the sun.

It's a place Londoner Mehak Aslam is keen to escape. She comes to meet us in the manager's office - a slight veiled figure, wearing a face mask and walking with a limp. She says she was beaten by Kurdish forces years ago and injured by a fragment of a bullet.

After agreeing to an interview, she speaks at length.

Goktay Koraltan/BBC

Goktay Koraltan/BBC

Kurdish troops patrol the area around the camps where IS detainees are held

Aslam says she came to Syria with her Bengali husband, Shahan Chaudhary, just "to bring aid", and claims they made a living by "baking cakes". He is now in al-Sina prison, and they have both been stripped of their citizenships.

The mother-of-four denies joining IS but admits bringing her children to its territory, where her eldest daughter was killed by an explosion.

"I lost her in Baghouz. It was an RPG [rocket-propelled grenade] or a small bomb. She broke her leg, and she was pierced with shrapnel from her back. She died in my arms," she says, in a low voice.

She told me her children had developed health problems in the camp, including her youngest, who is eight. But she admits turning down an offer for them to be returned to the UK. She says they didn't want to go without her.

"Unfortunately, my children have pretty much grown up just in the camp," she said. "They don't know a world outside. Two of my children were born in Syria, they have never seen Britain, and going to family who again they don't know, it would be very difficult. No mother should have to make the choice of being separated from her children."

But I put it to her that she had made other choices like coming to the caliphate where IS was killing civilians, raping and enslaving Yazidi women, and throwing people from buildings.

"I wasn't aware of the Yazidi thing at the time," she said, "or that people were being thrown from buildings. We did not witness any of that. We knew they were very extreme."

She said she was at risk inside the camp because it is known that she would like to go back to Britain.

"I have already been targeted as an apostate, and that's in my community. My kids have had rocks thrown at them at school."

I asked if she would like to see a return of an IS caliphate.

"Sometimes things are distorted," she said. "I don't' believe what we saw was a true representation, Islamically speaking."

After an hour-long interview, she returned to her tent, with no indication that she would ever leave the camp.

The camp manager, Hekmiya Ibrahim, says there are nine British families in Roj - among them 12 children. And, she adds, 75% of those in the camp still cling to the ideology of IS.

There are worse places than Roj.

The atmosphere is far more tense in al-Hol - a more radicalised camp where about 6,000 foreigners are being held.

We were given an armed escort to enter their section of the camp.

As we walked in - carefully - the sound of banging echoed through the area. Guards said it was a signal that outsiders had arrived and warned us we might be attacked.

Goktay Koraltan/BBC

Goktay Koraltan/BBC

About 6,000 foreigners are being held in al-Hol camp

Veiled women - clad head to toe in black - soon gathered. One responded to my questions by running a finger across her neck - as if slitting a throat.

Several small children raised an index finger - a gesture traditionally associated with Muslim prayer but hijacked by IS. We kept our visit short.

The SDF patrol outside the camp and in the surrounding areas.

We joined them - bumping along desert tracks.

"Sleeper cells are everywhere," said one of the commanders.

In recent months, they have been focused on trying to break boys out of the camp, "trying to free the cubs of the caliphate", he added. Most attempts are prevented, but not all.

A new generation is being raised - inside the razor wire - inheriting the brutal legacy of the IS.

"We are worried about the children," said Hekmiya Ibrahim back in Roj camp.

"We feel bad when we see them growing up in this swamp and embracing this ideology."

Due to their early indoctrination, she believes they will be even more hardline than their fathers.

"They are the seeds for a new version of IS," she said. "Even more powerful than the previous one."

Additional reporting by Wietske Burema, Goktay Koraltan and Fahad Fattah

15 hours ago

1

15 hours ago

1

English (US) ·

English (US) ·