Representative image (AI-generated)

Indian doctors and nurses have become indispensable to health systems across advanced economies, according to the International Migration Outlook 2025 released on Monday by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

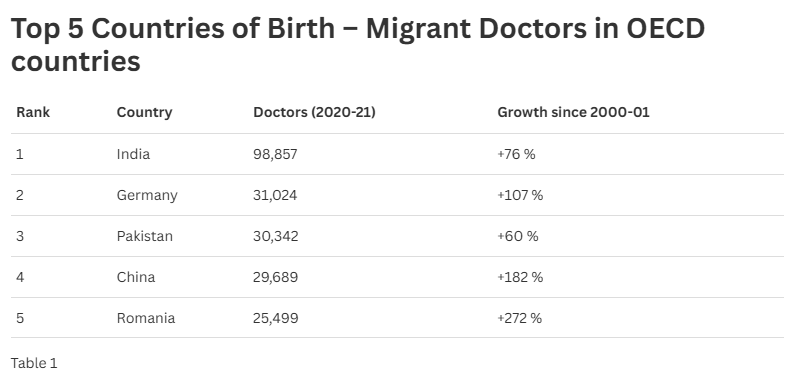

From the perspective of the 38 OECD member countries (which include the US, Canada, European nations, and Australia), the report states that the growing dependence on migrant medical professionals’ underscores both a lifeline and a vulnerability in global healthcare.The report finds that India is now the single largest source of migrant doctors and the second-largest source of migrant nurses working in OECD member countries.

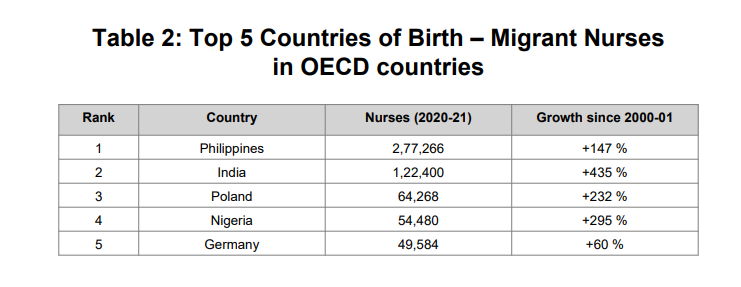

In 2020-21, there were 98,857 Indian-born doctors and 122,400 Indian-born nurses employed across OECD nations — up by 76 per cent and 435 per cent, respectively, since 2000-01.

.

OECD member countries housed more than 8,30,000 foreign-born doctors and 1.75 million foreign-born nurses, representing respectively about one-quarter and one-sixth of the workforce in each occupation. Asia is the main region of origin, accounting for approximately 40% of doctors, and 37% of nurses.

India, Germany, and China are the main countries of origin for doctors, while the Philippines, India, and Poland are the top three countries for nurses.“Migrant doctors and nurses are increasingly vital to the sustainability of OECD member countries’ health systems,” the report notes, adding that shortages are structural rather than temporary and will worsen without sustained international recruitment.

.

India’s dominance in global health mobility

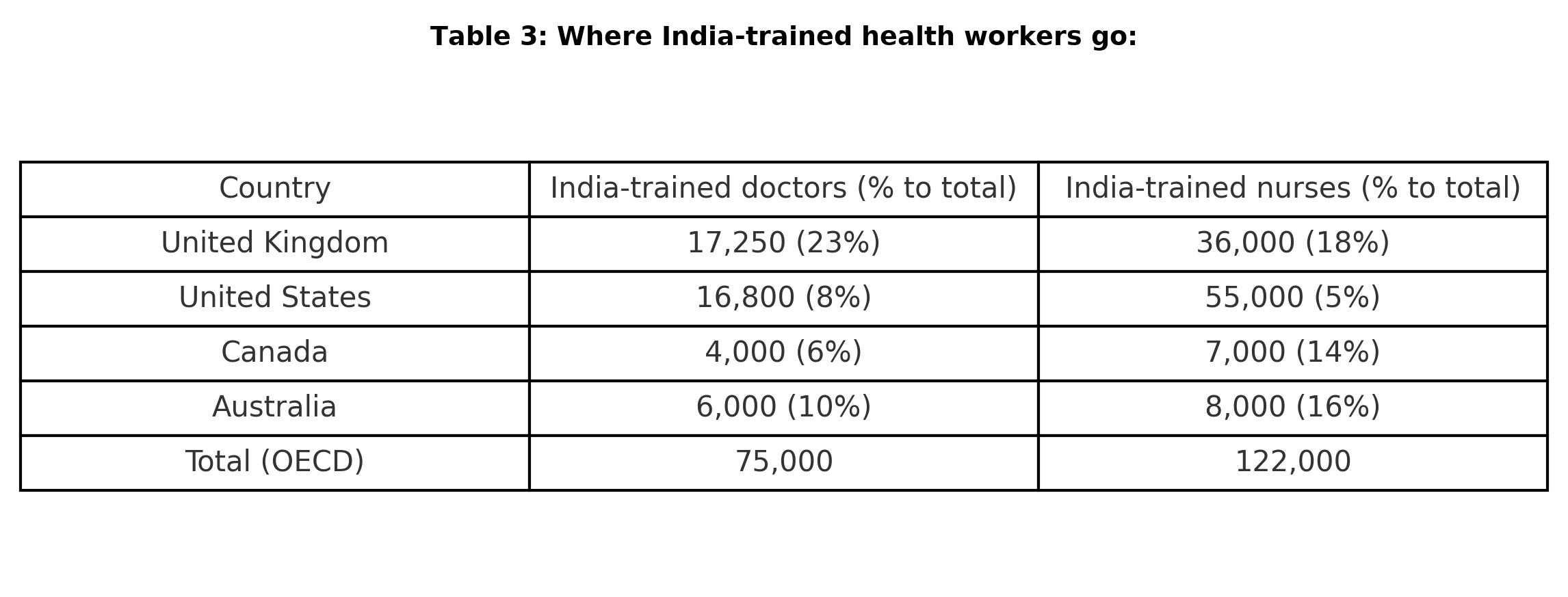

The United Kingdom (UK), United States (US), Canada, and Australia remain the largest destinations for Indian health professionals.The OECD report distinguishes between ‘foreign-born’ and ‘foreign-trained’ health professionals. The former refers to doctors and nurses who were born outside the country where they now work (some of whom may have received their medical education after migrating). Foreign-trained refers to those who obtained their primary qualification abroad. The number of foreign-born professionals is higher than the number of foreign-trained professionals, since it includes second-generation migrants and those who pursued local degrees after moving, explains the report.In 2021-23, OECD member countries had 6,06,000 foreign-trained doctors, of which 75,000 (12%) were India-trained. Against 7,33,000 foreign-trained nurses, India’s share was 17% or 1,22,000.Country-specific analysis is available only for 2021 and TOI broke down the numbers. The UK housed 17,250 India-trained doctors (23% of all foreign-trained doctors), underscoring India’s pivotal role in sustaining Britain’s National Health Service.

In the US and Canada, there were 16,800 and 3,900 India-trained doctors, comprising 8% and 4% of foreign-trained doctors in these countries. In Australia, the 6,000 India-trained doctors comprised 10% of all foreign-trained doctors.India-trained nurses also dominated these health systems. There were 36,000 India-trained nurses in the UK (18% of the foreign-trained nurses); 55,000 India-trained nurses, or 5% of the 1.1 million foreign-trained nurses, worked in the US.

Canada had 7,000 India-trained nurses (14% of 50,000 foreign-trained nurses), and in Australia, India-trained nurses constituted 16% of the 50,000 foreign-trained nurses — amounting to about 8,000.

.

The OECD report attributes India’s dominance to a mix of factors — the scale of its medical education system, English-language training, and targeted bilateral recruitment by OECD member countries. Between 2000 and 2021, the number of Indian-trained nurses working abroad grew more than fourfold, from around 23,000 to 122,000.

For doctors, the growth was steadier but substantial, expanding from 56,000 to nearly 99,000.The trend, however, raises the question of “brain drain.” India appears on the WHO’s Health Workforce Support and Safeguards List, which identifies countries facing critical workforce shortages.Many OECD member countries have relaxed migration pathways for health professionals. The UK has streamlined licensing under the Health and Care Worker Visa, although it recently restricted dependents from entry to curb overall migration.

Canada has created fast-track credential recognition for nurses from some countries, including those educated in India.Despite these openings, licensing and recognition of foreign qualifications remain major bottlenecks. The OECD’s report points out that “even when migration policies are supportive, delayed or opaque recognition procedures continue to prevent timely labour-market integration.” In several countries, migrant health workers end up in lower-skilled or auxiliary positions despite holding advanced credentials.

10 hours ago

1

10 hours ago

1

English (US) ·

English (US) ·