Islamabad, Pakistan – Pakistan’s Senate on Monday approved a constitutional amendment that aims to bring sweeping changes to the country’s judicial system and to the military’s command structure amid criticism that it seeks to weaken oversight over the government and leaders of the nation’s powerful army.

The proposed 27th Amendment eventually sailed through the Senate in a raucous evening sitting after the opposition boycotted the session.

Like in the Senate, the amendment now needs to secure a two-thirds majority in the National Assembly, the lower house of parliament, which is expected to vote on the draft on Tuesday afternoon. If it gets those votes, the amendment would need President Asif Ali Zardari’s signature to become law.

But both the contents of the proposed amendment and the manner in which the Pakistani government has sought to push it through have sparked criticism, including from senior sitting judges, even as other experts said the changes are justified.

The 27th Amendment of the constitution, if it becomes law, would in effect grant immunity from criminal prosecution to the top-most military leaders while also reshaping the military’s command structure. These would be through changes to Article 243 of Pakistan’s Constitution.

Separate provisions in the amendment aim to set up a Federal Constitutional Court (FCC), among other legal reforms.

But while many constitutional amendments are controversial, critics have questioned the rush with which the current amendment has been moved. Law Minister Azam Nazeer Tarar presented it in the Senate on Saturday, the same day that the cabinet approved it.

Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif – who was in Baku, Azerbaijan, on a state visit along with army chief Field Marshal Asim Munir – attended the cabinet meeting virtually before his return to Islamabad on Sunday.

After consultations within the government and with its allies, a revised draft was circulated in the Senate on Monday and passed the same evening. By contrast, the 26th Amendment, while also criticised by the opposition, followed months of public debate.

So what is the 27th Amendment all about? What makes it so controversial? And how are its defenders justifying it?

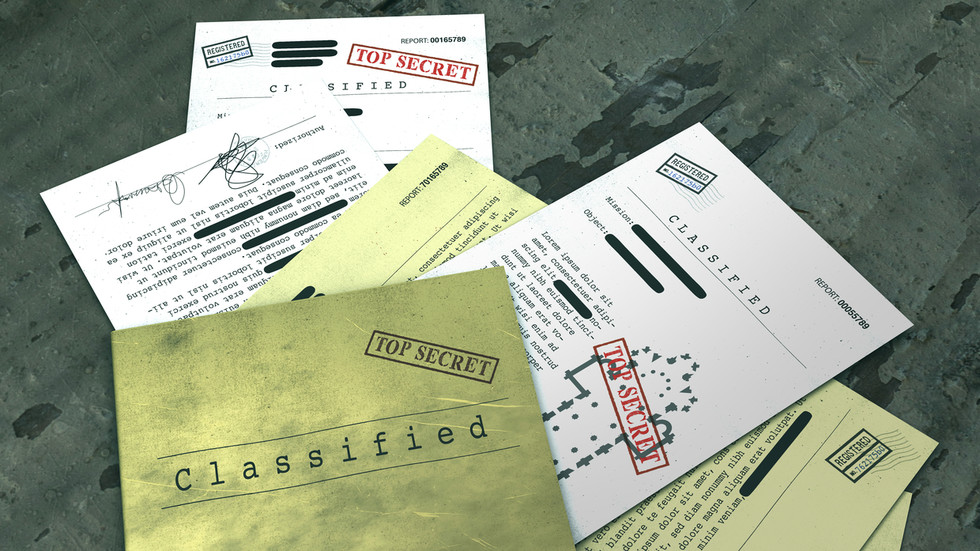

![President Asif Ali Zardari and Prime Minister Muhammad Shehbaz Sharif jointly conferred the baton of Field Marshal upon Chief of Army Staff (COAS) Field Marshal Syed Asim Munir during a special investiture ceremony at Aiwan-e-Sadr in Islamabad. [Handout/Government of Pakistan]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/credit-government-of-pakistan-1762792614.jpg?w=770&resize=770%2C582&quality=80) President Asif Ali Zardari, centre, and Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif, right, jointly confer the baton of field marshal upon Chief of Army Staff Asim Munir in Islamabad in May this year [Handout/Government of Pakistan]

President Asif Ali Zardari, centre, and Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif, right, jointly confer the baton of field marshal upon Chief of Army Staff Asim Munir in Islamabad in May this year [Handout/Government of Pakistan]How will it change Article 243 of the constitution?

Article 243 defines the relationship between Pakistan’s civilian government and the military.

The revision amends Article 243 to create a new post of chief of defence forces (CDF), to be held by the army chief. This essentially gives the army chief authority also over the air force and the navy. If the amendment is passed, the post of chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee (CJCSC) would be abolished later this month.

The CJCSC is currently held by four-star General Sahir Shamshad, who is due to retire on November 27.

Since independence in 1947, Pakistan’s military, especially the army, has been the most powerful institution in national life. Four coups and decades of direct and indirect military rule have entrenched that influence, and the army chief has long been the country’s most powerful figure.

Its current holder, Munir, became army chief in November 2022 and was promoted to five-star rank on May 20, just 10 days after the country ended its four-day conflict with India.

The 27th Amendment would also grant five-star officers lifetime immunity while allowing them to “retain rank, privileges and remain in uniform for life”.

Munir is only the second Pakistani military officer, after Field Marshal Ayub Khan in the 1960s, to have received the five-star designation. None of the other military branches, such as the air force or navy, has had a five-star official.

The proposed amendment also creates the post of commander of the National Strategic Command (NSC), responsible, among other things, for the country’s nuclear command. The head of the NSC would be appointed only from the army in consultation with the army chief/CDF.

According to the Pakistani Constitution at present, Article 248 stipulates that “no criminal proceedings whatsoever shall be instituted or continued against the president or a governor in any court during his term of office.” But once out of office, they enjoy no such privileges.

Military generals currently have no such immunity. Before the 27th Amendment, the title of field marshal was considered purely honorific with no additional powers or privileges. However, the proposed changes would essentially codify the ranking as a recognised constitutional position.

If the amendment passes, it would take a two-thirds majority in parliament to remove a five-star-ranked official – even though an elected government, by contrast, loses power when a simple majority in parliament votes against it. And a five-star officer would enjoy immunity from criminal prosecution for life.

“Democracy does not survive where impunity is made a constitutional right,” Rida Hosain, a Lahore-based constitutional lawyer, told Al Jazeera. “It grants a nonelected army officer protections and powers that no democratically elected leader in the country has.”

Pakistan’s proposed constitutional amendment would create a Federal Constitutional Court and render the Supreme Court only an “appellate court”, according to experts [Anjum Naveed/AP Photo]

Pakistan’s proposed constitutional amendment would create a Federal Constitutional Court and render the Supreme Court only an “appellate court”, according to experts [Anjum Naveed/AP Photo]What are the judicial changes?

The draft amendment seeks to create a permanent Federal Constitutional Court.

The FCC would be headed by its own chief justice and staffed by an equal number of judges from each of Pakistan’s four provinces as well as from Islamabad. It would adjudicate in disputes between governments, either the federal government and a state government or when different state governments clash.

Judges of the FCC would retire at 68, unlike Supreme Court judges, who retire at 65. The FCC chief justice’s tenure would be capped at three years.

The draft also gives the president power to transfer a judge from one high court to another on the proposal of the Judicial Commission of Pakistan (JCP), the body responsible for recommending appointments to Pakistan’s superior judiciary.

After the 26th Amendment was passed last year, the transfer of judges was to happen from one high court to another high court only through a presidential order.

However, the judge’s consent was necessary for a transfer as were consultation with the chief justice of Pakistan and the two chief justices of respective high courts.

That would change under the new revision: The president would be able to transfer a judge on the recommendation of the JCP without the consent of the concerned judge.

Additionally, if a judge refuses his transfer, he would be given an opportunity to present his reasons before the JCP, and if the body finds the reasons invalid, the judge would have to retire.

Hosain said the amendment would mean judges can be transferred to other jurisdictions without their consent while refusal could lead to proceedings before the Supreme Judicial Council, the body which holds judges accountable.

“The fact that refusal leads to accountability proceedings being initiated is a veiled threat that weaponises administrative power to enforce compliance. It transforms an independent judicial office into one overshadowed by the constant fear of punitive or retaliatory transfer,” she added.

Reema Omer, legal adviser for the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ), a Geneva-based nongovernmental organisation of judges and lawyers, said the new amendment has concerning implications, particularly in the short and medium term.

“The executive will appoint the judges who will have the sole jurisdiction to hold the executive accountable,” she told Al Jazeera.

“It appears this is being done to shield the existing set-up from judicial scrutiny and accountability. Also, if and when required, the FCC can be used to give constitutional cover and legitimacy to these decisions of this set-up,” Omer added.

Senior sitting judges have criticised the amendment too.

Mansoor Ali Shah, the second most senior judge of the Supreme Court of Pakistan (SCP), wrote in an open letter to Chief Justice Yahya Afridi on Monday stating that the FCC does not represent a “genuine reform agenda” but is instead a “political device to weaken and control the judiciary”.

Calling it a “manipulation of [the] judicial process”, Shah said such a court cannot be independent.

“History does not easily forgive such abdications of duty; it records them as constitutional failures of leadership and moments when silence within institutions weakened the very edifice they were meant to guard,” he wrote.

What do defenders of the amendment say?

The government’s rationale for bringing the changes to the constitution was presented in the draft of the amendment, in which it said the proposal stems from the increasing number of constitutional petitions being filed before the Supreme Court, which has “significantly impacted the timely disposal of regular civil and criminal cases”.

Changes to Article 243, the government has said, were proposed to improve the “procedural clarity and administrative structure relating to the armed forces”.

Some experts agreed.

Hafiz Ahsaan Ahmad Khokhar, an advocate of the Supreme Court, said a permanent FCC would provide “focused expertise and timely adjudication”.

“It is empowered to interpret the constitution, resolve federal-provincial disputes, determine the validity of laws and render advisory opinions. This ensures focused expertise and timely adjudication,” the Islamabad-based lawyer told Al Jazeera.

While the creation of the FCC will bring coherence, speed and discipline to constitutional adjudication, the introduction of the CDF office would unify strategic command and enhance coordination without disturbing the existing services’ autonomy, Khokhar argued.

“Both reforms are grounded in the realities of Pakistan’s governance challenges and increasing complexity of state functions. These measures will help Pakistan evolve into a mature, rule-based democracy where judicial, civil and defence institutions perform their specialised roles in harmony,” he said.

What are some of the deeper criticisms of the amendment?

But these explanations have so far failed to satisfy sceptics.

The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) questioned the urgency with which the amendment was tabled.

“The government’s haste, including the absence of any meaningful consultation with the political opposition, the wider legal fraternity and civil society, calls into question the very intention behind moving this amendment bill,” the HRCP said.

HRCP deplores the manner in which the 27th Amendment to the Constitution is being tabled in Parliament. The government’s haste—including the absence of any meaningful consultation with the political opposition, the wider legal fraternity and civil society—calls into question the…

— Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (@HRCP87) November 9, 2025

Omer of the ICJ warned the amendment marked a “fundamental change” for the judiciary.

“The 27th Amendment reduces the Supreme Court of Pakistan to only an appellate court. It is also no longer the ‘Supreme Court of Pakistan’ but only the ‘Supreme Court’ and its chief justice will be the CJ of the SC, not the CJ of Pakistan,” she said.

The judiciary, at least in the short and medium term, will be largely beholden to the executive, according to Omer.

“Any real accountability or review of the executive and parliament appears unlikely. And any relief to Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf against the wishes of the system also seems unlikely,” she added, referring to the largest opposition party, the PTI.

The PTI, led by former Prime Minister Imran Khan, who has been in jail for the past two years, governed from 2018 to 2022.

It was removed by a parliamentary vote of no confidence in April 2022. The party was disqualified from participating in last year’s elections, but independent candidates from the PTI nevertheless won the single largest share of seats (93) amid allegations of manipulation in the vote count, charges that the government rejected.

No party secured a majority, and Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif’s Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) formed the government in coalition with the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP).

Meanwhile, Hosain also cautioned that under the amendment, while the prime minister would continue to be exposed to political scrutiny and the will of elected representatives, immunity has been granted to the non-elected officials.

“It institutionalises the supremacy of the uniform over the ballot,” she said.

Omer pointed out that Pakistani political parties, including the PPP, now an alliance partner of the ruling PML-N, had in the past resisted constitutional protections to the military. That, she said, had now changed.

“The 27th Amendment is constitutional surrender,” she said.

2 hours ago

1

2 hours ago

1

English (US) ·

English (US) ·