Gary O'Donoghue

Chief North America correspondent

BBC

BBC

It was a warm, late May afternoon in 2024 in lower Manhattan. The jury in Donald Trump's trial over hush money paid by his former lawyer to adult film star Stormy Daniels was out deliberating for a second day.

Assuming we were in for a long wait, I took myself off to lunch with the BBC team at the world-famous Katz's deli for a Reuben sandwich.

Then all hell broke loose. The jury was returning.

According to one rumour, they were just being sent home for the day; another suggested there was a verdict.

Seconds before the BBC News at Ten went on air, I arrived breathless at the live television point outside the courthouse, smashing my phone screen on the pavement in my hurry.

One by one, the verdicts filtered through: guilty... guilty... guilty... it went on.

Getty Images

Getty Images

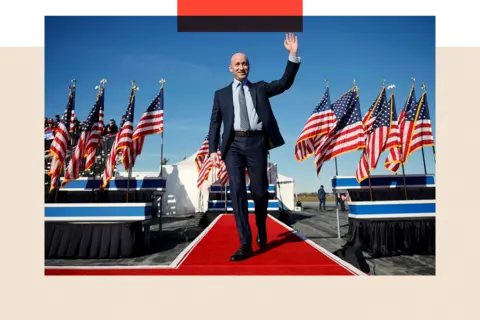

During his recent interview with Gary O'Donoghue, Donald Trump called judges who have suspended presidential executive orders "radical left lunatics"

All 34 charges came back guilty, and I spent that night's main news bulletin explaining the enormity of the idea that a former president was now a convicted felon – a first in US history.

As the BBC's senior North America correspondent, I'd spent months covering the multitude of Trump's legal problems in courts up and down the East Coast. Four separate criminal cases; several civil actions; it was coming at him from all sides, threatening not just his liberty but his whole political and commercial existence.

Spool on a year, and the boot is thoroughly on the other foot.

Three major Supreme Court judgments – one giving presidents and former presidents broad immunity from prosecution; a second dismissing the ruling that Trump's attempts to overturn the 2020 election results disqualified him from running for office again; and a third, just last month, curbing district judges' abilities to stall the president's agenda – have all emboldened this president who, having reshaped the Supreme Court with a solid conservative majority, now has the lower courts in his sights.

Reuters

Reuters

US Supreme Court justices at the Supreme Court in 2022

Those federal district judges – who had often made rulings on immigration policy that they said applied nationwide – are now facing a full-frontal onslaught from an administration that has questioned their legitimacy, and some say flouted their very authority.

The question is, should they fight back to reassert their authority – and if so, how can they? And will this all permanently reshape the balance of powers in the US, even after Donald Trump's term ends?

'The gravest assault on democracy'

Several judges – both active and retired – have told me that the scale of the "attack" is like nothing seen before.

John E Jones III, a former judge in Pennsylvania, appointed by a Republican president, and now president of Dickinson College, said: "I think it's fair to say that in particular, the US district courts… [are] under attack by the administration in a way that is unprecedented."

As well has his colourful remarks to me on the phone during our recent interview, the US President has variously called judges "crooked", "monsters", "deranged", "lunatics", "USA hating", and "radical left".

Getty Images

Getty Images

Deputy chief of staff for policy, Stephen Miller, has said that the country is living under a judicial tyranny

He has also called for the impeachment of those he disagrees with. And there have been threats to sue judges too.

His deputy chief of staff for policy, Stephen Miller, has been even more forthright, declaring that the country is living under a judicial tyranny.

"Each day, they change the foreign policy, economic, staffing, and national security policies of the administration," he posted on the social media site X in March. "It is madness. It is lunacy. It is pure lawlessness.

"It is the gravest assault on democracy. It must and will end."

From death threats to doxxing

Judges have faced growing hostility, and in some cases threats of violence from the public.

"[They] are facing threats that they never have faced before," says Nancy Gertner, a former federal judge who now teaches at Harvard Law School. She was appointed by President Bill Clinton and spent 17 years on the federal bench in Massachusetts.

"There's no question that the kind of opprobrium that the administration heaps on judges with whom they disagree is unlike any other time."

Judge Gertner says she knows of serving judges who have received death threats this year that are understood to have been prompted by their blocking or delaying some of the president's executive orders.

There is no suggestion that Trump had any knowledge of the threats.

Figures compiled by the US Marshals Service, which is tasked with protecting the judiciary, show that, to mid-June, there were more than 400 threats against almost 300 judges – surpassing the totals for the entire year of 2022.

Some of the threats involve doxxing – the publication of personal information about the person or their family, which risks opening them up to attack.

Other forms of intimidation this year have been more sinister still.

According to Esther Salas, a serving district judge in New Jersey, more than 100 judges have been subjected to fake pizza delivery orders.

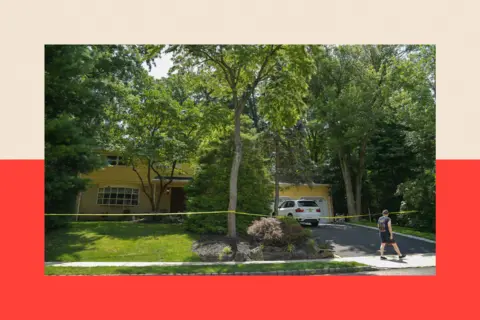

No big deal, you might think, but the deliveries are often accompanied with threats and in around 20 cases, the orders were placed by people who used the name Daniel Anderl, Judge Salas's late son.

He was killed five years ago by a disgruntled lawyer from a case heard by his mother. The assailant, who also shot her husband, had posed as a pizza delivery man.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Esther Salas's home following the attack in July 2020 that killed her son

Judge Salas told me of her reaction to hearing what was going on: "To say that I was angry is an understatement. And then of course, to have come home and tell my husband who nearly [died]."

The rise in threats began before the current administration but Judge Salas says we are in new territory now. "We are inviting individuals to do us harm when inflammatory rhetoric [is used]," she claims.

"That is giving a green light to anyone who thinks they may need to take things into their own hands. And our leaders know that."

Many supporters of the current administration including Jeff Anderson, one of the architects of the Project 2025 program (which many saw as a blueprint for Trump's second term), reject the idea that presidential rhetoric is to blame for raising the temperature.

Mr Anderson argues that the left is more to blame for hostility towards judges: "The most high-profile threat to anyone on the federal courts was when someone tried to assassinate [the conservative] Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh.

"There's this tendency to try to characterise the Trump administration as being what has facilitated this. I think a lot of the more radical revolutionary notions that we need to take law in our own hands and the ends justify the means… tend to [be] from the left in America."

A blizzard of executive orders

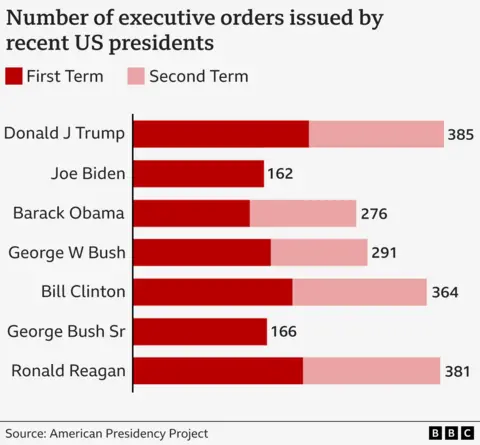

While other presidents have clashed with the courts, Trump's confrontations are unquestionably unique in their scale and fury, and they were perhaps inevitable, given that he arrived in the White House with a blizzard of executive orders aimed at getting what he wanted quickly.

On day one alone, 26 were signed.

There have been another 140 to the beginning of July – more than President Joe Biden signed during his four-year term, and only around 100 fewer than President Barack Obama in his eight years in the White House.

Trump could have asked Congress to enact laws to implement these policies; after all, Republicans currently control both chambers. But that process takes time, and Congress has been preoccupied with the president's flagship domestic legislation – the so-called "Big Beautiful Bill" – meaning that there has been no time or political capital for other priorities.

Of course, executive orders are perfectly within the president's prerogative. The power to make executive orders comes directly from Article II of the US Constitution, so Trump is not defying or bypassing the constitution – he's pulling the levers of government in a way he's allowed to do, provided the orders cite legislative authority; and those orders do have the force of law.

What the president can't do, with the sweep of his pen, is make new laws, or do things that go contrary to the Constitution.

And if Congress doesn't step in, then the only option for those who want to challenge the orders is to go to court.

Getty Images

Getty Images

While other presidents have clashed with the courts, Trump's confrontations are unquestionably unique in their scale

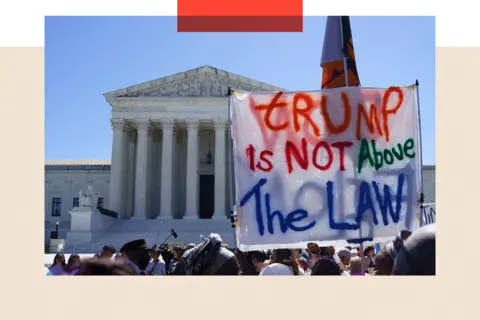

The sweeping nature of the orders he has signed, many touching on constitutional issues such as the right of everyone born in the US to citizenship, has led to dozens of nationwide injunctions pending the outcome on the merits of the individual cases.

That is why Trump's Supreme Court victory at the end of June, curbing such nationwide injunctions, is so significant.

"These district court judges have been totally out of line and out of control," argues Jeff Anderson.

Are judges blocking 'electorate desires'?

The administration has deployed various arguments. The judiciary has been accused of "overreach" and judges themselves accused of being "activists". But perhaps the most fundamental – and most philosophical – criticism is that they are standing in the way of the will of the people.

As Stephen Miller has put it, "out of control Marxist judges" are standing in the way of the "desires of the electorate".

It's an argument that, according to many judges, misunderstands the constitution in a fundamental way.

"We're a nation of laws, not men," explains judge John E Jones III. "A mandate to the president of the United States does not mean a mandate to disregard the law. That's evident, but this is papering over a fundamental disregard of the law and the constitution."

Getty Images

Getty Images

Executive orders are perfectly within the president's prerogative under Article II of the US Constitution

There are signs that some individuals in the administration, despite its assertions to the contrary, could well be toying with flouting the authority of the courts.

The president's border tsar, Tom Homan, went on television over a court's attempts to prevent the deportation of several hundred Venezuelans and said: "I'm proud to be a part of this administration. We're not stopping. … I don't care what the judges think."

But, in his interview with me last week, the President denied he was defying the judiciary, pointing out that when rulings have gone against him, he has sought remedy through the court process.

"I have too much respect for it to defy it. I have great respect for the judiciary. And you can see that," he told me, adding: "That's why I'm winning on appeal."

'The US faces a catastrophic situation'

Some vocal critics of the president go further and claim he's tearing up the whole system of checks and balances in which the three equal branches of government (the presidency, congress and the judiciary) each act as a break on the others.

"This is a huge turning point for the country," says Professor Laurence Tribe, one of the nation's foremost constitutional experts, who has become a forthright critic of the president.

He argues that Congress has ceased to perform its oversight function and fears "the United States is facing a catastrophic situation".

"The idea of three branches… was hatched at our founding - before the rise of political parties and before the rise of demagogues as effective and charismatic as Trump," he told me. "The whole system is completely out of balance."

EPA

EPA

That balance that Professor Tribe talks about has long been debated and the shift in power towards the presidency is not a new complaint.

After the Watergate scandal in the 1970s, which saw President Richard Nixon flout many of the norms followed by previous presidents, a whole slew of legislation was passed to curb the executive and make it more accountable.

But some of the changes involved merely adopting new norms such as publication of presidential tax returns and avoiding financial conflicts of interest – and this president has showed little concern to be seen to follow those norms.

The judiciary is fighting back

When it comes to the relationship between the presidency and the courts, though, even Nixon stopped short of defying their authority, eventually handing over the infamous Watergate tapes, after months of refusing to do so, once the Supreme Court unanimously ordered it.

Trump has come close to defiance. In one instance, after being ordered to facilitate the return of a man wrongly deported to El Salvador, Kilmar Ábrego García, the administration was accused of slow-walking the process of complying with the Supreme Court's decision.

Even Trump's Attorney General, Pam Bondi, said: "He's not coming back to our country."

It took two months for the administration to follow the court's order. That was seen by the president's critics as a taste of what could follow.

After all, there are only two ways a president can be truly held to account – one is by removal at an election; the second is by impeachment in Congress, and Trump has already survived two of those.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images

This battle is far from over – and its consequences for future presidents are unpredictable

But if there truly is a plan to defy or neuter the courts, the judiciary is not giving in without a fight.

Even after the Supreme Court ruled to curb those nationwide injunctions at the end of June (incidentally, presidents of both parties have complained about such injunctions in the past), another judge slapped one on Trump's asylum policy.

Earlier this month, a US district judge issued a fresh nationwide block on Trump's executive order restricting the automatic right to citizenship for babies born to undocumented migrants or foreign visitors, drawing more furious words from the White House.

This battle is enjoined, but it's far from over – and its consequences for this president and future presidents are unpredictable.

Top image credits: Bloomberg via Getty and EPA-EFE/REX/Shutterstock

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.

6 hours ago

1

6 hours ago

1

English (US) ·

English (US) ·