Each generation has its symbol of revolt and revolution. In the 2010s, Millennials brandished the mask from "V for Vendetta" during the Arab Spring protests and Occupy Wall Street. Today, Generation Z seems to have discovered its own protest symbol: a skull and crossbones flag where the skull is sporting a straw hat. The image, originally from the popular "One Piece" Japanese manga, has become a symbol of their hunger for justice and change.

For the past few months, this flag has been popping up on banners and flags during protests all across the globe and lighting up social media. The demands vary between countries, but Gen Z youth in Indonesia, Nepal, the Philippines, Madagascar, Morocco and many other countries are rising up… and are adopting this manga flag as a symbol of their efforts.

This particular Jolly Roger flag belongs to Luffy, the hero of the cult manga "One Piece". It isn’t a coincidence or a wink to pop culture that so many youth protesters around the world have adopted this flag as their symbol: it is representative of the ideology championed by a large segment of this generation.

Protesters in Asia – in Indonesia, the Philippines, and Nepal – first started carrying the flag, but it quickly spread across the globe. In Madagascar, people made it their profile picture to show their support for local protesters. Some protesters in France carried posters or banners featuring Luffy’s flag during protests held on September 10. Later, it was also picked up by some members of Morocco’s GenZ 212, an internet-born movement calling for social justice, better healthcare and education systems, and a fight against corruption.

‘There are lots of critiques in 'One Piece' of the elite, of governments, of lies’

"One Piece", created in 1997 by Eiichirō Oda, tells the story of Monkey D. Luffy, a young pirate seeking the legendary "One Piece" treasure, which will make him king of the pirates.

"One Piece" became the most widely sold manga in history. There are more than 500 million copies in circulation across the globe. It was translated into 40 languages.

Younès (not his real name) is from Casablanca. This 26-year-old is part of the GenZ 212 movement in Morocco.

"Most people from my generation grew up with this manga because it has been coming out once a week for the past 28 years. I’ve been following Luffy’s adventures for the past 14 years, and there are millions of others like me out there. We’ve created an emotional attachment to the characters, it is like they are members of our family."

Faly (not his real name) is a Malagasy medical student. He took part in the protests in Madagascar in late September. He says that he fell in love with the story that "One Piece" tells about rising up against the established order.

"In the anime, the heroes are often teenagers who fight against an extremely corrupt ruling class – repressive governments rife with nepotism. That’s what inspired us, whether we are in Indonesia, Nepal or Madagascar. We created this Gen Z movement, not a political party. There isn’t a leader, just young people who are fed up. That’s what makes heroes: they make their anger known, and we’re making ours known too.”

The ability to read "One Piece" as a political document develops with age, Younés says:

"When we were little, we didn’t always see the political nature of the work. But as we grew, the level at which we were reading it changed. The author does flashbacks and you start to understand what happened differently. We started picking up parallels with our current world. There are lots of critiques of the elites, of governments, of lies. There is this idea that history is written by the victor. So if the same people always win, the ‘bad guys’ are always the same.

What’s exceptional about this work is that we are following the story of a pirate, who is normally an antagonist. Except, as you read, you discover that the real bullies are the navy and the government, who are supposed to be the nice guys, to help people. But in reality, they are corrupt and serve only their own interests. The real good guys are the pirates who fight against the government’s corrupt elites for the good of the people."

‘'One Piece' perfectly depicts the reality that we are living right now’

For the young protesters, "One Piece" isn’t just a fictional story, says Faly:

"The anime perfectly depicts the reality that we are living right now: the poverty, the gap between the rich and the poor. We used this symbol to demonstrate that to the world, because it is easy to recognise. 'One Piece' is well known all around the world. It is a symbol of rebellion. In ‘One Piece’, they are pirates, outlaws. We aren’t outlaws, but this shows that we won’t be fooled by the government and that we are ready to fight."

Younès shares this sentiment:

“Universal themes are embodied in 'One Piece', so it is a common language for this generation. Police, militaries and governments say that they are protecting the people but, ultimately, they are the ones doing harm. They use the media to make people believe that the pirates are the bad guys, they lie to create propaganda."

The Moroccan student adds that Luffy, whose flag has been taken up by protestors, really embodies the figure of a defender of the oppressed.

"He takes the risk to defend people who aren’t aware that they are going to be hurt. He takes the risk of fighting against bad guys. Just like the protesters who take to the streets to defend the rights of others, to fight for others even if they don’t know who you are."

‘There's a growing disconnect between what the governments are promising and what the citizens are actually experiencing’

Romi Ghimire is a lecturer and a human rights advocate in Nepal. She sees many common themes amongst the global protest movements.

"The recent protests in Nepal and those we've seen in countries like Indonesia, Madagascar, and Morocco, I think they reflect a powerful global trend. People, especially the youth, they are standing up against systemic failure and demanding dignity, accountability, and basic rights. In Indonesia, people protested elite privileges and the failure of public health programmes. In Madagascar, people protested the lack of basic necessities like water and electricity. Young people in Morocco are asking why the government can build stadiums for the World Cup but not provide jobs and education and basic services for their people. In every case, there's a growing disconnect between what the governments are promising and what the citizens are actually experiencing."

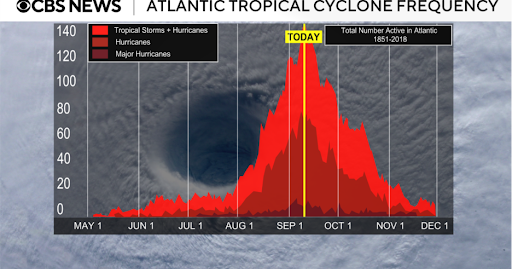

Despite these common themes, some of the protesters highlighted local specificities as well. In Nepal, the focus has been on the so-called nepo kids, for example, while in Indonesia, people were protesting privileges afforded to politicians. In Madagascar, people have been protesting about access to basic services. In Morocco, there was a number of issues that converged: ranging from the second anniversary of the 2023 earthquake (more than 2,000 deaths), the deaths of eight women during childbirth in a ten-day period at Hassan II hospital in Agadir and the inauguration in early September of the Moulay Abdellah stadium in Rabat. Protesters are angry at the government for pouring money into sports while schools and hospitals remain in terrible conditions.

This article has been translated from the original in French.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·