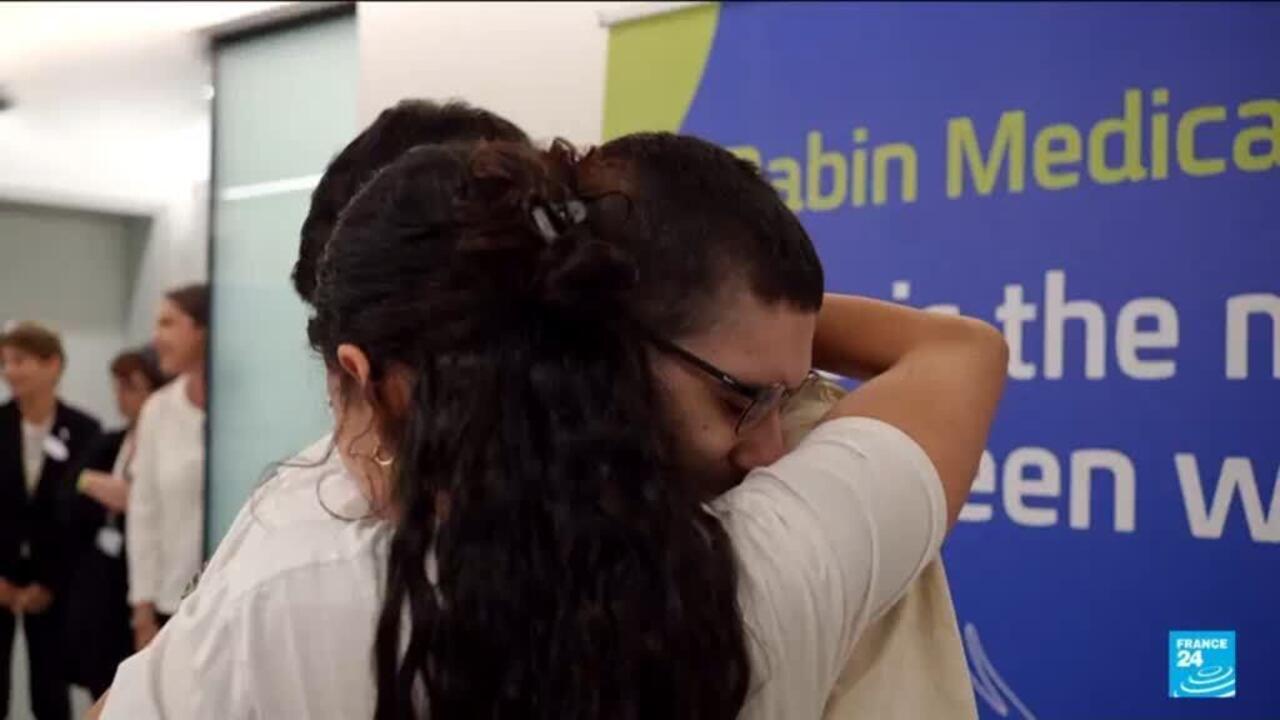

At the Rabin Medical Center east of Tel Aviv, emaciated former hostage Evyatar David rushes to hug his brother Ilay and sister Yeela. “I’m so happy to have you in my arms,” his brother says.

The three are all smiles as tears of relief trickle down their cheeks. “I’ve waited for this for so long,” Evyatar responds.

“Us too,” his sister chimes in.

After two years held in captivity by Hamas in the war-shattered Palestinian territory, the last remaining living hostages were returned from Gaza to Israel on Monday as part of a truce that included the release of more than 1,900 Palestinian prisoners in exchange.

Stories start to emerge over Israeli hostages' detention conditions

To display this content from YouTube, you must enable advertisement tracking and audience measurement.

One of your browser extensions seems to be blocking the video player from loading. To watch this content, you may need to disable it on this site.

01:56

Like Evyatar, all of them were men aged between 21 and 48 years old. They all appeared exceptionally thin and pale, a likely result of enduring long stretches of time without sunlight or food. They will all be needing ongoing medical, psychological and social rehabilitation.

But the road to recovery is long, with complications that can arise months or even years down the line.

The return

All 20 men were driven by the International Red Cross to a military base in southern Israel on Monday, where they could have their first medical examination. They were then transported to one of three Israeli hospitals slated to take them in – Ichilov Hospital, Sheba Medical Center and Rabin Medical Center, all located in or close to Tel Aviv.

Dedicated hostage reception units were set up before their arrival, and it's in these facilities that most of the former captives were able to reunite with their families for the first time.

As they settle into a life of freedom, the former hostages slowly go through a series of tests that serve as the basis for an individualised treatment plan designed by a multidisciplinary team of healthcare workers, including trauma doctors, psychiatrists, social workers and dieticians. Specialised physicians like neurologists or infectious disease experts can also step in if needed.

Read moreA week into fragile ceasefire, people of Gaza ‘have started to breathe again’

“The priority is stabilisation,” says Dr. Hagai Levine, head of the health team at the Missing Families Forum. “Treating injuries and infections, carefully reintroducing nutrition to prevent refeeding syndrome, restoring fluids and electrolytes, and ensuring physical and emotional safety.”

In the more than 700 days spent in captivity, most of the former hostages suffered periods of starvation, resulting in dramatic weight loss. Refeeding syndrome is a dangerous medical condition that happens when food is reintroduced too quickly, which can set off fatal hormonal or metabolic shifts. Returnees also face significant damage to their immune system, as a lack of nutrients can lead to a drop in white blood cells and anaemia. Other risks include complications with internal organs like kidneys, brought on by dehydration. And many of the men wore leg chains for the entirety of their captivity, potentially leading to orthopaedic issues, muscle deterioration and blood clots.

As well as needing intensive physical care, the former hostages' vulnerable psychological states require “privacy, calm and restoring a sense of control", Levine explains. Deprived of a sense of autonomy for two years, the physician explains that it is essential to allow the returnees to make small decisions on a consistent basis. Guidelines from the Israeli health ministry state that everyone treating the former hostages should ask for permission before carrying out an action, including turning the lights off or changing bedsheets, to ensure a gradual return of autonomy.

The Israeli government provides former hostages with a welcome kit that includes a laptop and mobile phone. But exposure to the outside world and everything that happened while they were being held in captivity is something Levine says should be reintroduced slowly.

“Many people they know were murdered. They became international figures. That is something to [grapple with], that your private life was so exposed,” he told MSNBC the day after the hostages were returned.

In previous releases, some of the former hostages and their families opted to stay together in a hotel close to Tel Aviv for a few weeks in order to adjust to their new reality, while others went home after being dispatched. Sheba, one of the medical facilities hosting them, has said they can stay as long as they need.

Invisible, long-term challenges

Arbel Yehud spent 500 days in captivity before she was freed earlier this year, as part of a January ceasefire deal. She was finally reunited with her partner Ariel on Monday, after spending two years apart.

Speaking alongside the families of other newly freed hostages at a press conference on Wednesday, Yehud said: “We could have brought them back a long time ago.” It was not the first time she had expressed anger at Israeli authorities, who she had previously accused of endangering captives by stalling negotiations.

Critics of the Israeli government and its Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu argue that the war could have ended months earlier than it did, with the previous January ceasefire. But the truce only held until mid-March, when Israel resumed its strikes on Gaza. Among former hostages, feelings of abandonment or betrayal can often arise, leaving them grappling with the notion that part of their traumatic experiences could have been avoided.

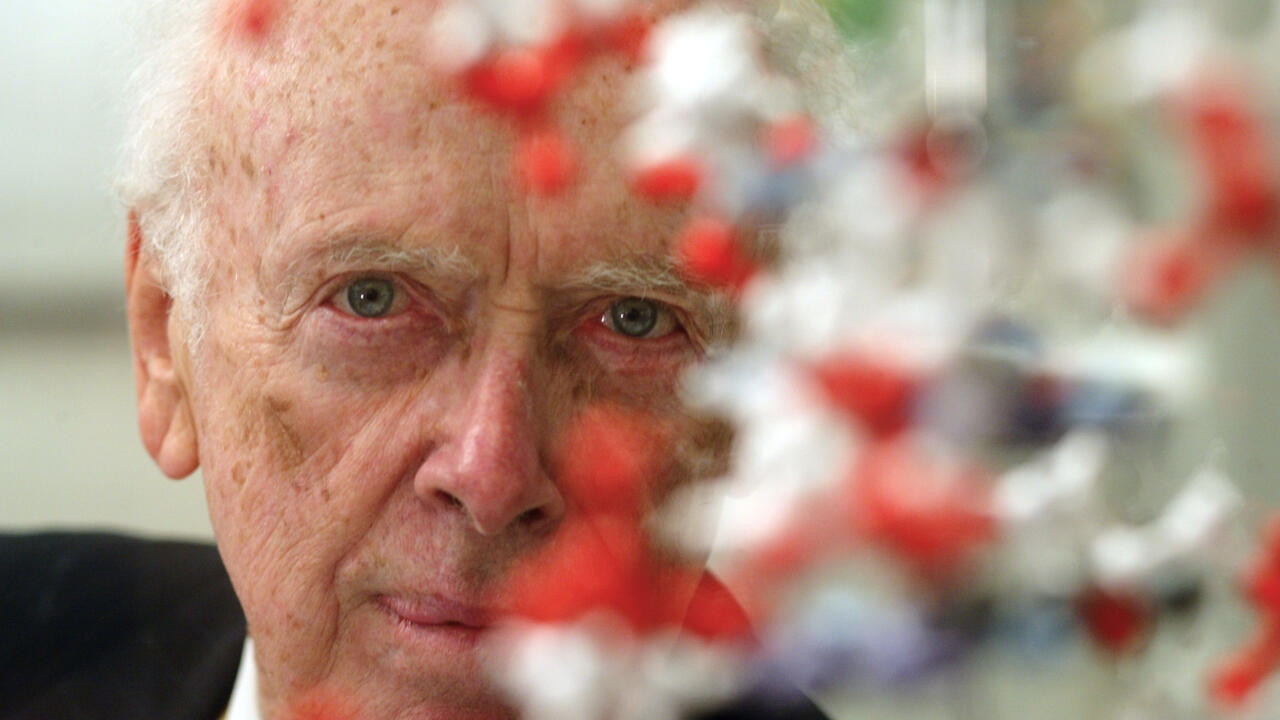

It is something that Avi Ohry, who spent 44 days in Egyptian captivity during the Yom Kippur War, can relate to.

Read moreFrom 1947 to 2023: Retracing the complex, tragic Israeli-Palestinian conflict

“I had the same feeling. Why did nobody succeed in helping us in the beginning of the war? How come the strongest army in the Middle East was [caught off guard] in 1973? It is the same nowadays, this feeling that the [Israeli] brigades along the Gaza Strip could have prevented the massacre. We failed,” he says.

Many former hostages also speak of the survivor's guilt they feel, knowing that other captives in Gaza did not make it out alive – or learning that their loved ones were killed during the October 7 attacks.

A year after his release, Ohry took on a residency in rehabilitation medicine at the Sheba Medical Center, the same hospital hosting returnees from captivity in Gaza today. He is now a doctor specialised in rehabilitation medicine and has spent decades putting together proper guidelines on how best to support former captives.

The feelings of abandonment expressed by former hostages can also be compounded by a lack of long-term support by health authorities. “It is essential that [former captives] are accompanied along the years, to follow-up on complications that may develop later,” Ohry says.

“Decades after being released from captivity, physical and mental problems can pop up. There can be diabetes, heart disease, vascular problems, cancer, but also depression or post-traumatic stress disorder,” the doctor explains. “Or even a combination of all these.”

“In order to try and detect these complications as early as possible, we need a follow-up system,” Ohry says.

Hostage medicine

Shortly after October 7, a team of Israeli medical, military and social welfare workers began updating a manual on best practices for the rehabilitation of former hostages. With every new release, new lessons were included. Variables like age, ranging from children to the elderly, but also the time spent in captivity added a new course of action or list of specificities when it comes to treatment.

But one year after returning from captivity, hostages were experiencing a “shortage of resources, guidance, and psychological care, as well as a lack of systematic follow-up", a report by the Missing Families Forum read, according to Israeli daily Haaretz.

So with each new release comes a new set of lessons. After having treated hostages freed from captivity in January and February this year, the Rabin Medical Center opened an entirely new department called the Returning Hostages Unit. Families are given rooms in the units so they can stay with their loved ones, and returnees are treated by a range of healthcare professionals. The hospital has also opened a long-term unit so that medical teams can offer continued support months or even years after hostages are discharged.

“The experience in Israel is unique and has, in practice, created a new discipline – hostage medicine. Never before have medical teams had to care for such a large and diverse group of individuals [...] infants, toddlers, children, women, young adults, older people,” Levine says. “It is an unprecedented situation that is reshaping how health professionals think about recovery.”

While Ohry is optimistic about the advancements in rehabilitation treatment, he believes improvements can still be made. “People are scattered all over the country, so we have to make sure that authorities take care of these people for life,” he says, referring to the long-term unit at the Rabin Medical Center near Tel Aviv.

Ultimately, the doctor hopes that the guidelines drawn from his own experience in what he calls “my war” and other instances of captivity will continue to be integrated and improved as time passes.

“I believe more change is coming, but I don't belong to this generation of doctors and psychologists,” Ohry says. “We will know the conclusion of this phase of rehabilitation treatment in the future.”

English (US) ·

English (US) ·