Reports coming out of the western Sudanese city of El-Fasher on Tuesday evening, as the RSF paramilitary group seized the city, detailed unprecedented levels of bloodshed in a conflict that has already been defined by extreme violence.

Within 48 hours, RSF attacks on the city had left more than 2,000 civilians dead, according to armed groups allied to the Sudanese army.

The UN cited credible reports of “summary executions, attacks on civilians along escape routes, house-to-house raids, and obstacles preventing civilians from reaching safety” along with widespread sexual violence against women and girls.

Meanwhile, Yale University’s Humanitarian Research Lab found evidence suggesting “systematic mass killings” on such a scale that blood stains on the ground were visible in satellite imagery.

Read morePapers on Sudan: A massacre so bloody, you can see it from space

It said the violence included attacks on health facilities, health workers, patients and humanitarian aid workers.

But the primary targets were non-Arab groups, including the Fur, Zaghawa and Masalit peoples.

The UN said around 177,000 civilians are still trapped inside the city by a 56-kilometre blockade built by the RSF that is sealing off food, medicine and escape routes.

Meanwhile, an estimated 26,000 have fled in recent days. Many travelled on foot to the town of Tawila, 70 kilometres west of El-Fasher, arriving with “horrific” stories of “widespread ethnically and politically motivated killing and indiscriminate violence”, the UN said.

Read more‘Humanitarian aid in Sudan is constantly being blocked by all the belligerents’

Ongoing conflict

The RSF takeover in El-Fasher is the latest chapter in Sudan’s turbulent history.

Tensions flared once again after the 2019 ousting of President Omar al Bashir, who ruled Sudan for 30 years.

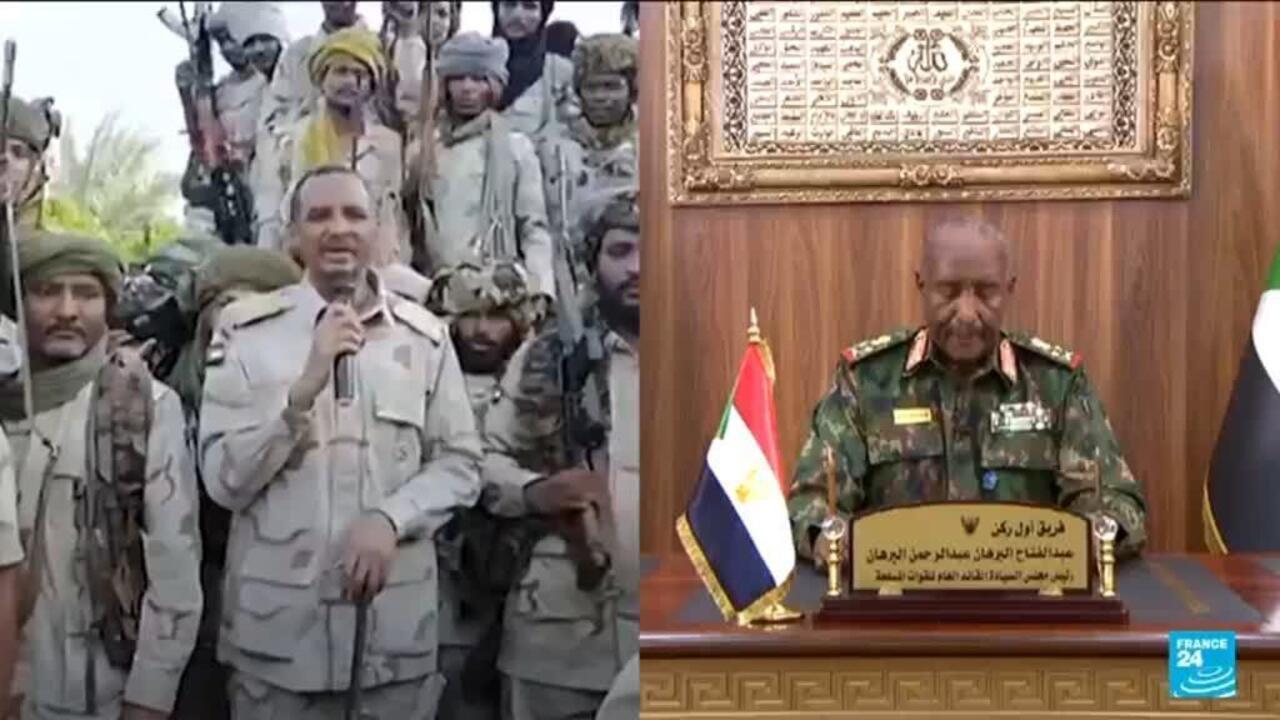

The current civil war began in April 2023 as a dispute between two high-powered generals: the head of the country’s armed forces Abdel Fattah al Burhan, and his former deputy Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, the head of the RSF paramilitary group.

To display this content from YouTube, you must enable advertisement tracking and audience measurement.

One of your browser extensions seems to be blocking the video player from loading. To watch this content, you may need to disable it on this site.

02:24

The conflict has been marked by extreme violence – just over a year after fighting began, it had already claimed an estimated 150,000 lives. By July 2025, 12 million people had been displaced and parts of the country had been pushed into famine.

Both sides have been accused of attacking civilians and committing serious violations of international law.

Prior to the RSF takeover, El-Fasher was subject to an 18-month siege marked by starvation and bombardment.

In the city, “civilians were already weakened by famine and have suffered carpet bombing from government forces, as well as a long RSF-imposed siege”, said David Keen, professor of conflict studies at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE).

Currently, the army controls much of north and east Sudan, including most of the border with Egypt, which is said to be one of Burhan’s main backers.

It also holds urban centres in Port Sudan – the home of Burhan’s UN-recognised government – and in the capital Khartoum, where it regained control from the RSF in March.

Meanwhile, the RSF controls almost all the western region of Darfur, now including El-Fasher along with much of central Kordofan region and a small territory along Sudan's border with Libya and Egypt.

The army claims the RSF is backed by the UAE, which the Emirates denies.

'Darfur's lynchpin'

Taking control of El-Fasher is a significant advance for the RSF.

Logistically, the city sits at a crossroad of trade routes, including trafficking routes to access fuel, ammunition and weapons from Libya and Chad.

Politically, the seizure of El-Fasher gives the RSF almost complete control of west Sudan, effectively partitioning the country into two territories.

“El-Fasher is Darfur’s lynchpin, the last major city not under RSF control and the political centre of non-Arab armed groups,” said Dr Matthew Sterling Benson-Strohmayer, Sudan's research director at the LSE.

“Its fall grants the RSF near-total dominance of western Sudan, likely neutralising rivals and transforming Darfur from a periphery of rebellion into the heart of a paramilitary state,” he added.

The RSF declared in April that it was forming a rival government, raising the prospect that Sudan could split for a second time after South Sudan seceded in 2011.

In such a scenario, “the RSF’s patterns over the past twenty years suggest its rule will be defined by coercion”, said Sterling Benson-Strohmayer, including “systems of taxation, looting and tightly controlled aid”.

'A point of no return'

Experts fear that RSF rule in the western region will give the group free rein to eradicate the non-Arab groups that live there.

The paramilitary group is descended from the Janjaweed militias that were accused of committing genocide in Darfur between 2003 and 2005.

In 2023, the RSF was accused of carrying out massacres in West Darfur's capital, El-Geneina, killing up to 15,000 people from the Masalit group.

“In many ways, the current massacres mirror those in El-Geneina,” Keen said. “Retaliatory killings were widely expected to occur once RSF took El-Fasher, and these killings are now clearly taking place on a horrific scale.”

“We have been warned that mass killings of civilians would likely follow the fall of El-Fasher,” agreed Alex de Waal, director of the World Peace Foundation research organisation.

“All the warning signs for genocidal massacre are flashing red.”

Such violence may well mark a “point of no return”, he said, serving to “further polarise Sudan and jeopardise any chances of peace or state reconstruction”.

Already there is little appetite for negotiation between the army and the RSF.

"The prospects for peace are very minimal," Sudanese analyst Kholood Khair told AFP. "Neither the army nor the RSF, for strategic or battlefield reasons, is willing to commit to a ceasefire or genuine peace talks."

Typically, “when one side suffers a defeat, it wants first to avenge the defeat before talking. And when one side has scored a victory, it wants to press home its momentum before talking," said de Waal.

"This has long added up to a formula for continued war.”

English (US) ·

English (US) ·