The sunlight filtered through the ancient oak trees to the sound of birdsong and the crackle of autumn leaves underfoot.

At first glance the scene might have come from a painting by Camille Corot or Théodore Rousseau or any of the other artists who settled in the village of Barbizon on the edge of the Fontainebleau forest in the 1830s, setting up studios outdoors to draw directly "from nature".

But on a bright November morning a couple of centuries later, the signs of the current climate crisis were all too plain to see.

The needles of some of the parched Scots Pines had turned red and fallen to the ground months before.

The crown of one of the towering oak trees – usually a bright and luxuriant orange at this time of year – was completely bare.

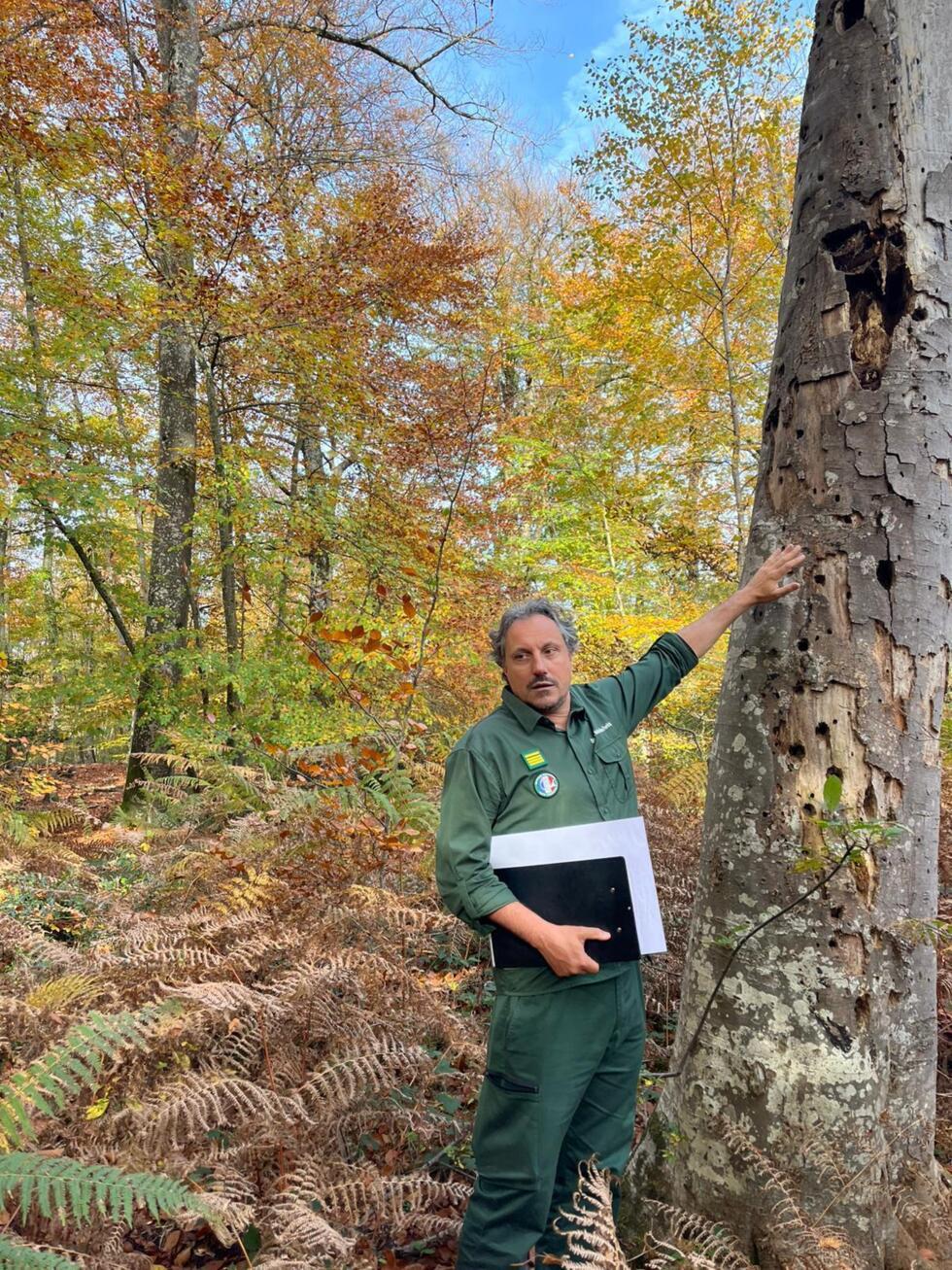

“This tree suffered from hydric stress and cavitation,” explained Alexandre Butin, the deputy head of the ONF's (National Forestry Office) regional unit that manages the 25,000 hectares of forest lying some 60 kilometres southeast of Paris.

“The tree’s roots struggled to absorb water from the forest’s soil. Air bubbles formed in its vessels, preventing sap from reaching the branches,” he said, gesturing to the tree’s naked and stunted boughs that continued to reach for the sky. The thirsty tree could no longer breathe and died from suffocation.

A few hundred metres away in the undergrowth stood a “cemetery” of beech trees. Their fine and delicate bark makes them particularly susceptible to intense heat.

Read morePrivate French forests become lucrative targets for timber thiefs

“They have no suncream to put on,” quipped the forester, as he gave one of the fragile trunks an affectionate pat.

“These trees are the visible face of the effects of global warming,” said Butin, adding that a perfectly healthy tree can die in just 15 days.

A 'pilot site that offers solutions'

The impact of the climate crisis in Fontainebleau was first felt many years ago. The trees sit on a fine sandy floor which struggles to retain water, making the forest particularly vulnerable to the ravages of climate change: intense droughts, unpredictable rainfall, violent storms and forest fires.

This summer alone, around 50 fires – often sparked by a stray cigarette butt from one of the millions of visiting tourists – blazed through the forest, burning through four to five hectares of land.

Every year since 2017, when the ONF launched the DEPERIS protocol to monitor the forest’s health and track fires, drones fly overhead and scan around 765 deciduous trees. A tree in perfect health is graded A while those considered to be “completely degraded” are ranked as F.

In just seven years, the number of trees rated between D and F has almost doubled, rising to 40%, with a peak of 48% during the drought of 2022 – a particularly devastating year for the forest.

But the unforgiving soil has also put the foresters at Fontainebleau ahead of the curve, Butin explained, adding that his fellow foresters – who were only just beginning to see the impacts of the climate crisis – came to study what the ONF calls a “laboratory for adaptive forest management”.

“We are a sort of pilot site that offers solutions,” said the jovial Butin. “We like to say we’re about 20 years ahead of our colleagues in other regions.”

New seedlings planted each winter

In 2021, faced with alarming reports on the health of the trees, the ONF decided to give the forest “a helping hand” by diversifying species and planting around 60,000 new seedlings each winter.

Just a few metres from the forest trails, young downy oak trees – prized for their longevity, resistance to drought and fine grain – grew in plastic tubes amid the surrounding bracken and ferns.

Read moreThe 'green gold' of French forests

The downy oak is also favoured by foresters for its strong genetic adaptability – it can pass on its entire “history” to subsequent generations, giving it greater resilience to climatic variations.

Other oak saplings stood in wooden enclosures fringed by barbed wire and birch trees to protect them from wild boars, and from direct exposure to the heat and the wind. Some of the seedlings were planted in small groups so they could compete with each other for sunlight while others grew in isolation.

And alongside the traditional oaks, beeches and Scots pines, the foresters have planted southern European species that are more resistant to drought: service trees and fruit trees such as pear and apple.

“We let nature take its course whenever possible. But in areas where the soil is very poor and tree species are unable to regenerate on their own, we try to help them,” said Butin, adding that the ONF intervenes in around 20-30% of the forest.

Always taking their cue from the state of the soil, the foresters also assess how best to structure and layer the forest with trees of different heights and diameters to build its resistance and prevent it from “collapsing like a house of cards”.

Otherwise, “An entire forest can be wiped out in a storm,” said Butin.

‘Mosaic forest’

Over centuries of both human influence – woodcutting and grazing – and natural regeneration, Fontainebleau evolved into a “mosaic forest” – a patchwork of mini-forests made up of birch groves, oak plantations, sandy clearings, rock formations, silvery ponds and wetlands.

It is partly this variety of ecosystems that draws so many of the forest’s tourists – roughly 11 million ramblers, rock climbers, campers, cyclists and horse riders visit each year.

The foresters hope that the pockets of new plantations will gradually blend into the patchwork to increase its resilience.

“Not all trees grow at the same pace. We want to have enormous diversification in our forests, meaning at least five species,” said Butin.

“The idea is not to put all our eggs in one basket,” he said. Indeed Butin’s role is akin to that of an orchestra conductor – he juggles managing the trees’ health and the forest’s biodiversity alongside the demands of the timber industry and the visiting tourists.

A tree in perfect health that risks falling on a picnic table will be removed. But most of the trees that have either died from “hydric stress” or cavitation or been felled by a vicious storm are left on the ground. Their decaying trunks provide shelter and food to hundreds of insects, mosses, lichens, birds and bats – boosting roughly 30% of the forest’s biodiversity.

“Fontainebleau is a good place to experiment with adaptation,” agreed Xavier Morin, director of the Centre for Functional and Evolutionary Ecology in Montpellier. “As soon as there is a slight drop in rainfall, there are major impacts.”

Since the Fontainebleau forest “also shares many characteristics with lowland forests in central France", the measures implemented here can be replicated in other French forests, the forest ecology researcher added.

In the early 19th century, the artists who became known as the Barbizon School of painters protested against the timber industry’s felling of Fontainebleau’s oak trees – saying they were ruining the forest’s landscape.

By 1861 –11 years before Yellowstone in the US was made a national park – Napoleon III decreed that 1,000 acres of the forest at Fontainebleau would be an “artistic reserve” – effectively creating the world’s first conservation site.

Now it’s the turn of the foresters to continue to protect the woodlands’ shifting landscape from the ravages of climate change.

“I trust in nature, and we are here to help her. Nature regularly reminds us of the humility we must have in the forest,” said Butin.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·