After one too many drone incursions, European leaders appeared to have had enough, gathering in Copenhagen on Wednesday for back-to-back summits on security and Ukraine.

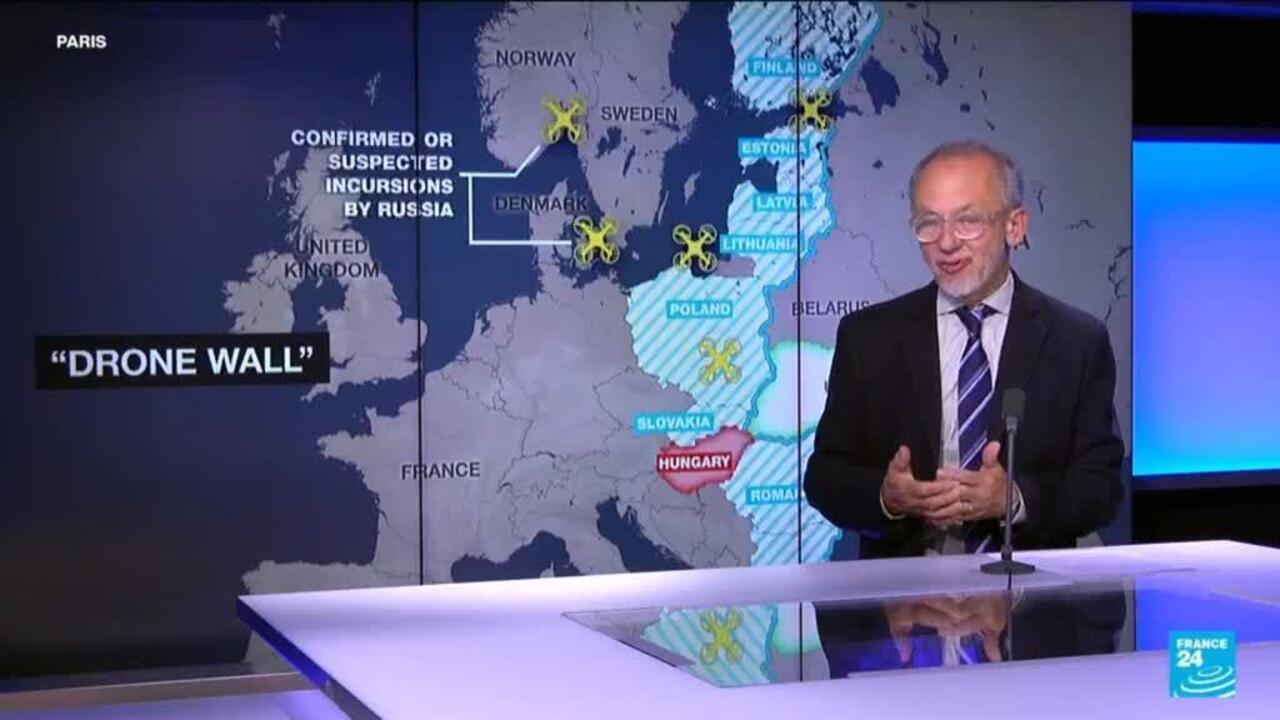

At the top of the agenda is a proposed “drone wall” to shield the EU’s eastern flank from Russian incursions. Backed by the European Commission, the plan would combine detection and strike systems along borders recently breached by drones in Poland and Romania and by MiG-31 jets in Estonia.

The meeting came after unidentified drones, suspected of being launched from vessels linked to Russia, forced airspace shutdowns in Denmark and Norway last week.

Read moreDenmark drone incursions: All signs point to Russia?

A wall in 12 months?

Despite repeated incursions, the drones themselves were never located, but Russian involvement remains the main suspicion. Danish authorities described the overflights as the work of a "professional actor" and a "systematic threat", while stopping short of directly accusing Moscow, which has firmly denied any involvement.

To display this content from YouTube, you must enable advertisement tracking and audience measurement.

One of your browser extensions seems to be blocking the video player from loading. To watch this content, you may need to disable it on this site.

06:19

French authorities said on Wednesday they were investigating the Boracay, a Benin-flagged tanker anchored off Saint-Nazaire and suspected of being part of Russia's "shadow fleet" used to skirt Western sanctions. Prosecutors cited violations including failure to justify the ship’s nationality and refusal to cooperate. The Maritime Executive reported the tanker and other vessels may have been linked to the drone flight.

Read moreFrance probing Russian-linked oil tanker for ‘serious offences’, Macron says

"It is vital right now to find how to defend against the growing number of drone incursions. And quickly, because Europe’s security landscape has already changed with contested airspace," said James Patton Rogers, a drone warfare expert at Cornell University.

The concept of a "drone wall" has therefore gained urgency. European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen cited it in her State of the Union speech last September as “the foundation of a credible European defence”. Lithuanian defence commissioner Andrius Kubilius went further, suggesting in an interview last week with Euractiv that the wall should be completed in "12 months".

Experts, however, warn that such a timeline may be ambitious. "It depends on what you call a 'drone wall'," said Rogers. "It should not be imagined as a wall that would make the EU impermeable to any incursion from Russia or Belarus, the main threats in this area." Julian Pawlak, a Baltic security specialist at the Bundeswehr University in Hamburg, added that it is "a political call to act, since there is no technical framework yet for such a defence system".

Better drone detection

Kubilius stressed that the quickest part to implement would be detection. Recent incursions, including the 20 drones that breached Polish airspace earlier this month and the repeated Danish overflights, exposed Europe’s unpreparedness.

Preventing hostile drones from entering EU airspace will likely require "a multilayered system of sensors and detectors", said Justinas Lingevicius, a new-tech security specialist at Vilnius University. Radars would only be one part of it.

"To identify drones, there are devices that process acoustic signals or monitor different electronic frequencies," explained Bruno Oliveira Martins of the Peace Research Institute Oslo. Drones can produce specific sounds and be remotely controlled on certain radio frequencies.

Once detected, drones could be neutralised. There are several options. "The most common method is to jam drones’ sensors by overwhelming them with a flood of radio signals. It is also possible to take control by 'hacking' their systems," Martins said. Finally, these drones can be destroyed "either with projectiles such as small missiles, or by sending other drones to collide with them", he added.

Practical obstacles

The "drone wall" faces significant practical hurdles, starting with geography. The wall would need to stretch along the Eastern borders of at least ten countries – Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Bulgaria, Denmark, Romania, Hungary and Slovakia, Lingevicius said.

Yet borders may not be enough. "The threat can also come from inside Europe. In Denmark, for example, the drones could have been operated from another European country," Pawlak said. A wall would be useless if Russia managed to plant agents inside the EU.

In Poland, authorities arrested two people – a Belarusian and a Ukrainian – accused of flying a drone over the presidential palace in Warsaw in September.

Watch morePoland detains 2 Belarusian citizens flying drone over president's residence

Technology is another hurdle. "Drones are becoming smaller and faster, making them harder to spot," Martins said.

Artificial intelligence also plays a key role. In the field of drones, it "enables the creation of large swarms that can fly in formation and operate autonomously", Martins said. Such swarms could easily overwhelm the interception capabilities of a "drone wall".

"Practical questions remain,” added Lingevicius. “Do we already have the technology? Can we produce enough drones? And how long would it take to train their operators?"

Cat-and-drone game

Even with the right tools, counter-drone systems age quickly. It is a cat-and-drone game, and the war in Ukraine "has shown that the lifespan of drones and the systems to counter them is around six weeks", Rogers said. After that, capabilities must be updated to keep pace.

That makes the wall an ambitious goal that "will require continuous investment to stay effective against an evolving threat", Rogers added. "It is clearly a very costly programme," acknowledged Pawlak.

Politics may be the hardest barrier. The Commission unveiled €150 billion in defence loans in September, much earmarked for Eastern Europe. "But debates will arise over how the funds are distributed," said Pawlak.

Countries such as Hungary and Slovakia, both close to Moscow, could obstruct or slow down progress.

Europe’s defence cooperation is also notoriously slow. "Processes take time, and it is fair to ask whether the EU can keep up with innovation," said Lingevicius.

Fortunately for the EU, notorious for its slow decision-making, "the pace of innovation will not always be this fast", said Pawlak. But experts insist that is no excuse to wait. "Drones are a threat that will not disappear overnight. They will still be here after the war in Ukraine," he added.

All the more reason to begin building the "drone wall" now.

This article has been translated from the original in French by Anaëlle Jonah.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·