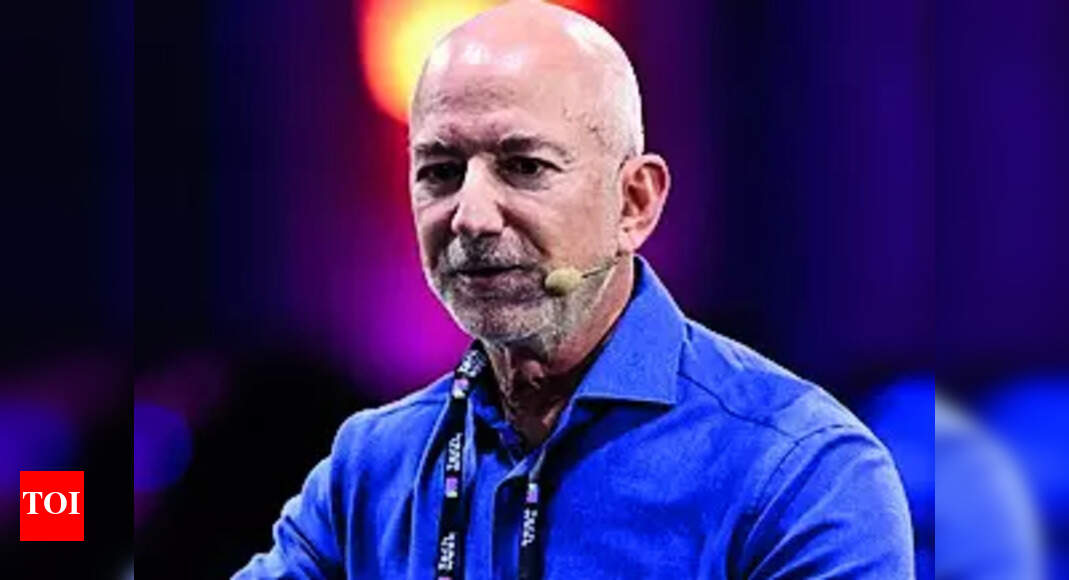

In the half century he navigated the heights of U.S. executive power, Dick Cheney went from being universally admired—as the competent public servant overseeing the lopsided victory in the First Gulf War—to profoundly polarizing, albeit in ways that made many Americans wistful: The divisions Cheney inveigled were grounded not in personal aggrandizement but in differing concepts of duty to nation. His legacy at the time of his death on Monday, at 84, was as the uniquely powerful Vice President who after the terrorist attacks of 9/11 intrigued for the CIA to use torture, for the National Security Agency to scoop up the communications of every American, and for the misbegotten military invasion of invade Iraq, which killed hundreds of thousands and shifted the balance of power in the region to Iran while expanding the terrorist threat.

Cheney made himself, hands-down, the most powerful Vice President in U.S. history, mining the powers of the office so effectively that, in the first term of President George W. Bush, he was described as regent, the nominal subordinate who wields the real power over a boy king. His reputation for stealth and rigidity gratified conservatives, and in liberal circles sketched a caricature of villainy that found an apotheosis in Vice, the 2015 feature film that portrayed Cheney (played by Christian Bale) as a henpecked bumpkin who a few scenes later was a diabolical mastermind.

Read More: Tributes Pour In for Former Vice President Dick Cheney, Who Has Died at 84

His ascent to power was, in fact, meteoric. And no American politician in modern history moved so swiftly from light to shadow without the accelerant of personal scandal. “He would run the gauntlet of being the toast of America after Gulf War One and then being ‘this monstrous hideous person, this warmonger, torturer—‘blow up the world!’’’ his late friend Alan Simpson, said in 2021. “And he isn’t. He’s the same person.”

Cheney elected to embrace the notoriety, joking in speeches about his reputation as “Darth Vader” and in 2007 dressing his black Labrador for Halloween as the Dark Lord of the Sith. The reputation distracted, perhaps shrewdly, from Cheney’s failure, as the official Bush had placed in charge of terrorism, to heed warnings about 9/11. After the attacks, he would say he did not recall meetings in which an attack was called imminent.

Other parts of the caricature were entirely accurate.

Cheney genuinely preferred working in the shadows, eyebrow cocked in meetings where he maintained a Sphinx-like silence. In a city where information is power, Cheney warned subordinates not to characterize his views to outsiders while manipulating the processes of a federal government he had learned from the inside out. (Except for five years as chairman at the oil services firm Halliburton, which reportedly paid him $44 million, he never worked anywhere else.). Former aide Eric Edelman noted that, in the Bush White House “we put our own gloss on” documents produced by the National Security Council, which passed through Cheney’s office before going to the President, as did all emails between staff. Cheney was the only Vice President who saw the President’s daily threat report before the President did.

“He was always going to be probably both the most powerful and the most controversial Vice President in history,” says Edelman, who was Cheney’s national security aide. “He knew where everything was, where the bodies were buried inside the Administration, and that gave him an enormous opportunity to provide the President with a realm of advice in private. Which he did.”

Cheney was an avid student of both power and of mortality, intrigued by the mechanics of presidential succession decades before assuming the office whose only official duties have been described as presiding over the Senate and “inquiring daily into the health of the President.” His own health was a topic of constant speculation; the first of five heart attacks came at age 37. By the time of he was Vice President, he physically embodied both paranoia and prudence: In 2007, the cardiac defibrillator implanted in his chest had its wifi specially disabled, against any possibility of a malign actor sending a signal that would induce cardiac arrest in the man a heartbeat from the presidency. His life was extended for 13 years by a heart transplant in 2012.

Richard Bruce Cheney was born on Jan. 30, 1941, in Lincoln, Nebraska, the son of a civil servant. When he was 13, the family moved to Casper, Wyoming, where his father worked in the Soil Conservation Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. A local alumnus got Cheney a free ride to Yale, where he washed out and returned to Wyoming, installing electrical lines and drinking enough to be twice arrested for drunk driving. After his high school sweetheart, Lynne Vincent, “made it clear she wasn’t interested in marrying a lineman for the county,” as Cheney told biographer Stephen F. Hayes, he earned a masters at the University of Wyoming, then pursued a PhD in political science at the University of Wisconsin, using first student and then family deferments to avoid the Vietnam draft. His parents were Democrats, and by his own account he might have become one, too, if the last opening for a state legislative intern had not been with the Republican caucus. Cheney said he “didn’t have a political identity” at the time.

He would acquire one in Washington, D.C, during an ascent so rapid it could have been written by Charles Dickens, or Horatio Alger, if either had thought to place a hero in the U.S. federal bureaucracy. In just six months, Cheney moved from a temporary fellowship on Capitol Hill to a White House office. He studied the interior of government from beneath the wing of Donald Rumsfeld, whom he succeeded as Chief of Staff to President Gerald Ford in 1975. It was a formative period in more ways than one. The son of a federal employee would later say his skepticism of government activism was informed by troubleshooting political interference and corruption in the Office of Economic Opportunity, the LBJ-era War on Poverty clearinghouse that he helped Rumsfeld run. His expansive views on Presidential power were rooted in his resistance to the constraints Congress imposed after the Watergate scandal (which Cheney avoided by sitting out the Richard Nixon 1972 campaign).

“Cheney had a very broad view of executive power,” noted Jack Goldsmith, who after taking over the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel discovered the secret torture and surveillance programs Cheney had put in place. The Vice President argued (to the Supreme Court, no less) that neither Congress nor the courts had any right to compel information from the executive branch –that the President was simply beyond oversight. When Donald J. Trump was conniving to remain in office after losing the 2020 election, Cheney’s maximalist reputation made him an effective advocate for the rule of law, organizing a letter of warning signed by all ten living former defense secretaries.

Rumsfeld’s signature on the group letter amounted to a coda in something Washington rarely produces: a buddy movie. After a terrible first meeting, the former Michigan Congressman had given Cheney not only his first White House job, but vouched for the younger man to the newly installed President Ford (who had been inclined to dump Cheney over the drunk driving convictions), then effectively shared the Chief of Staff job with his nominal deputy before ceding it to him. The dynamic prefigured the White House of Bush 43, which the Veep largely staffed, and substantially dominated. Associates said Bush trusted the older man because he demonstrated no appetite to become President himself. For his part, Cheney was content to exercise his discreetly assembled powers secure in the knowledge that the Vice President was the only person a President cannot fire.

He had taken the job, famously, after W. Bush placed Cheney in charge of finding a running mate in his 2000 campaign. Less well known was that, after compelling would-be candidates to surrender their most sensitive secrets in hopes of landing a spot on the ticket, Cheney in at least one case used the information against the aspirant, Barton Gellman recounts in his deeply reported account of Cheney’s vice presidency, Angler. The book takes its title from Cheney’s Secret Service code name.

Cheney was becoming an oxymoron—a famous Vice President. But not a popular one. He had been around Washington for decades: running Ford’s losing 1976 campaign, then, after being elected to Wyoming’s only House seat, chairing the Republican caucus, serving as whip. But the public first knew Cheney as, along with Joint Chiefs Chairman Colin Powell, the quietly confident, visibly competent public face of the 1990-91 Gulf War that ejected Iraqi troops from Kuwait (and the gates of Saudi Arabia) in just 100 hours of ground combat. But the war failed to knock out Saddam Hussein, and in the months before the 9/11 terror attacks, it was the Iraqi dictator, not al-Qaeda, that preoccupied the man Bush fils had placed in charge of intelligence and anti-terrorism.

On the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, Secret Service agents lifted Cheney out of his chair by his belt (“they must rehearse it,” he later said), and hustled him into a command bunker beneath the White House on reports that a hijacked passenger jet was headed their way. With the President airborne, the Vice coolly directed the response to the attacks, at one point ordering U.S. fighter jets to “take out” passenger jets that may have been hijacked. In the months that followed, one descriptor of the nation’s fears was Cheney’s announced work station: “a secure, undisclosed location.” Inside the Administration, “The Dark Side” was the shorthand for the architecture Cheney constructed against the Hobbesian world he now saw: Secret legal memos that would give CIA employees legal cover to torture suspects confined in third countries, and coaxing the NSA to nudge aside institutional respect for the Fourth Amendment and widen its surveillance to include all telephone calls originating in the United States.

“We were flying blind,” Edelman recalls. “We used enhanced techniques [torture] because we didn’t know much…Was the juice worth the squeeze? I guess the record will say, maybe not. Cheney in his own defense will say we knew almost nothing about al Qaeda in 2001.” To justify going to war against Iraq—which had played no role at all in the 9/11 attacks—Cheney reached into the bureaucracies to cherry-pick intelligence that would support deposing Saddam. The Iraq adventure diverted key intelligence and Special Forces assets from Afghanistan (from which Osama bin Laden had ordered 9/11) and 20 years later both countries continue to be plagued by terrorist groups, including ISIS, spawned by the U.S. occupation of Iraq.

Cheney appeared unperturbed by all of it, especially his thuggish image. “That’s exactly what he thought: ‘I don’t give a sh-t,’” said Simpson, before his own death in March. “So they poured it on him, waterboarding, torture, twisted sneer.” On the Senate floor in 2004, the Vice President actually told Patrick Leahy, the Vermont Democrat, “Go f—k yourself.” But Bush was in his second term the February 2006 morning that Cheney peppered the face and torso of a 78-year-old lawyer with lead shot during a quail hunt. Both wars had become quagmires, and Cheney—who repeatedly offered to leave the ticket as Bush approached the 2004 campaign—was no longer being called “regent” in a White House that was no longer his. For Bush, a point of departure was a seismic rebellion by the heads of the FBI and Justice Department over the secret domestic surveillance program. For his part, Cheney believed Bush had failed a loyalty test, having refused to pardon Cheney aide “Scooter” Libby on charges that grew out of the Veep’s attempts to justify the Iraq invasion through leaks to the press.

3 hours ago

1

3 hours ago

1

English (US) ·

English (US) ·