BBC

BBC

A young man is rescued from the rubble of an apartment block in El Karak

At the wheel of an ambulance, Samir El Chekieh drives with sirens wailing to the latest Israeli air strike in El Karak in the Bekaa Valley, eastern Lebanon.

The 32-year-old firefighter and paramedic with the Lebanese Civil Defense Force (CDF) only got a few hours' sleep last night. It is now the middle of the afternoon and he still hasn’t had breakfast.

Since the escalation of the war between Israel and the Shia Muslim Hezbollah, the men and women of the CDF see little rest, and brace themselves for a mass casualty incident every day.

This article contains graphic descriptions

It is starkly different from the last war with Israel in 2006, Samir says. “We didn't have those kind of air strikes. Recently, a fire station was hit, and a church in the south, and our humanitarian colleagues have been killed.”

Darren Conway / BBC

Darren Conway / BBC

Samir El Chekieh is a firefighter and paramedic with the Lebanese Civil Defense Force

CDF workers say civilians, including women and children, are increasingly among the dead and injured when they attend a call out.

The war between Israel and Hezbollah is spreading deeper and wider across Lebanon.

An intense bombing campaign has broadened far beyond the country’s southern border villages and the capital Beirut, to towns in the fertile Bekaa and the historic city of Baalbek, principally Shia areas, where Hezbollah was founded. The port cities of Sidon and Tyre have also seen an increase in attacks.

Israel says it is only targeting Hezbollah fighters, weapons and infrastructure. Since its campaign against the militant group escalated, Israel estimates it has destroyed two-thirds of Hezbollah’s rocket and missile stockpile.

But Hezbollah is still firing rockets daily towards Israel.

The BBC spent two weeks with Civil Defense Force crews in the Bekaa Valley, which stretches eastwards to the border with Syria. Permission from Hezbollah was required to visit the scene of Israeli attacks.

In that time, the number and frequency of strikes in the area dramatically increased.

On 28 October, there were more than 100 Israeli strikes, and in the past week alone 160 people were killed in the Bekaa, according to official figures. The Lebanese government does not distinguish between fighters and civilians in its figures.

Samir and his men arrive in the Shia village of El Karak to find chaos and destruction - the air is thick with smoke and dust.

Earlier at their station in the nearby city of Zahle, they had heard a powerful explosion - and from their balcony seen a plume of smoke in the distance. They jumped into their fire trucks and ambulances and headed straight there.

Darren Conway / BBC

Darren Conway / BBC

Samir and his crew look for bodies in the rubble in El Karak

A woman in chador sits on the pavement begging to be let into the smoking ruins of an apartment block, but men reason with her to stay put. It is too dangerous, a second Israeli air strike could be coming.

The first body they find is of a man, blown across the ground by the explosion.

There are survivors underneath the pancaked floors of the apartments and Samir goes deep in the rubble. He is not wearing plastic protective gloves as fire is still blazing inside, so when he finds a child, he can feel shattered bones beneath his fingertips. As he carefully retrieves the child, he realises it is only half a body.

“The first victim I found was a child. I don't know if it's a girl or a boy,” he tells me afterwards. “Sorry to explain that. But it's from the stomach and up - from stomach and down there is nothing.”

In the past, the CDF crew have received phone calls telling them to evacuate a site they are attending. They assume they are from the Israelis. No such call comes on this day, so for an hour Samir and others dig deeper into the ruin.

Eventually they find a 10-year-old girl alive. She tells the rescuers that her eight-month-old brother, Mohammed, was next to her.

“After that, we started hearing the screaming of a small child,” Samir says.

Through a small crevice in the rubble they spot the trapped boy, trying to move his legs, his babygrow and a single blue sock visible to the rescue crew. They painstakingly remove the debris around him and he is gently cradled in Samir’s hands and brought to safety. Mohammed is now being treated in Iraq for the head injury he suffered, his family says.

Darren Conway / BBC

Darren Conway / BBC

“We don't ask the sex of the victim. We don't ask if he's black, white. We don't ask if he's Christian or Muslim. We are humanitarians,” says Samir

The CDF works across Lebanon’s sectarian divide. It does not discriminate, says Samir, who is Christian and is the head of operations at the station in Zahle - a predominantly Christian town, dominated by a statue of the Virgin Mary, which rises 54m above a hilltop.

“We don't ask the sex of the victim. We don't ask if he's black, white. We don't ask if he's Christian or Muslim. We are humanitarians,” Samir says.

The UN estimates that every day in October at least one child was killed and 10 were injured in Israeli attacks. Those losses, combined with those of their colleagues killed in strikes, are taking their toll on Samir and his men.

Almost 24 hours after they left the El Karak site, a second Israeli attack brought down the rest of the apartment building.

In the early evenings, Hezbollah still fires rockets from nearby hillsides, targeting Israel. One salvo of at least six projectiles causes a brush fire near Zahle.

In the town of Khodor, the Hezbollah flag is planted on the ruins of one of the many buildings that have been flattened by Israeli bombs. Children’s toys have been arranged at its base. A large red Shia flag flaps in the wind nearby - it is almost the only sound in the largely abandoned town.

Bekaa is being hammered by relentless Israeli air strikes

With a bandaged head, Jawad Hamzeh takes me through the rubble of his home.

His three daughters died in the attack, including 24-year-old Nada who was pregnant. He holds up another daughter’s law books, she was studying to be a lawyer.

There were no militants here, he says. “Where are the missiles, do you see them?” he asks.

The Iranian-backed Hezbollah began attacking Israel on 8 October 2023 in solidarity with its ally Hamas, which had carried out a devastating attack on Israel the day before. Months of cross-border exchanges followed, and then, in late September this year, Israel assassinated Hezbollah’s leader, Hassan Nassrallah, and followed that with a ground invasion.

Hezbollah is committed to Israel’s destruction, but it is more than a militant group. It is the most powerful political force in Lebanon and a social movement which serves as a bulwark for Lebanon’s long-discriminated Shia communities against other sects in the country.

Tens of thousands of Israelis have been displaced by the year-long war. By attacking Hezbollah on multiple fronts, Israel hopes to degrade the group and let its people return home.

Despite US-led ceasefire talks, neither side appears willing to back down.

On 30 October, the Israeli military issued an evacuation order in the Bekaa city of Baalbek, which the UN described as the “largest forced movement Lebanon has experienced in a single day” since the start of the conflict. As many as 150,000 people were given only hours to flee another Israeli assault.

There, not far from the magnificent Roman ruins with its towering temple of Bacchus, I met Hussein Nassereldine, 42, whose home had been destroyed in an Israeli strike the night before.

“No terrorist or bad person lived here,” he says. “All who lived here were decent people.” He says it was home to families who had fled Beirut in 1982 during the country’s civil war, including his own. “We were born here and lived here, and we will stay and won’t leave here,” he says.

As I leave, men with pickaxes and shovels are making slow progress in the rubble and Hussein prepares to erect a tent on what was left of his home.

Darren Conway / BBC

Darren Conway / BBC

A displaced family sleeps outside on the streets of Beirut

Outside the city, at the Dar Al Amal hospital, the injured are recovering from Baalbek’s deadliest day. Of the 63 people killed, two thirds of those were women and children according to the local governor. Israel says it struck 110 Hezbollah-linked targets.

In a bare room, filled only with screams, three-year-old Selin’s tiny hand reaches out for comfort. But there is no-one there. She has burns to her face, a fractured leg and wounds to her groin and side. Her mother, father, two sisters and brother were all killed in the Israeli air strike that left her broken and alone.

Darren Conway / BBC

Darren Conway / BBC

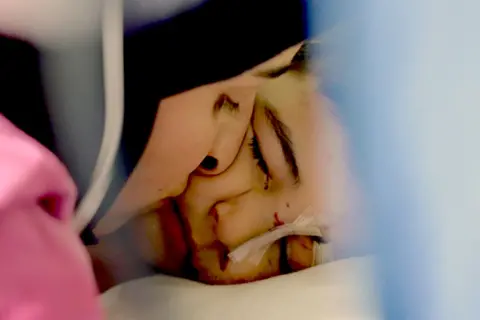

Najat Smeha kisses her two-year-old son Kayan, he is in hospital with a fractured skull

Across the corridor of the intensive care unit, two-year-old Kayan Smeha has a fractured skull. His mother, Najat, 24, kisses him gently on his cheek and cradles him to quieten him.

“He is still panicking,” she tells me. “And he is probably re-running the scene as I am doing. I can handle it, but he is small, he can’t.”

Tears roll down her cheek, but she is defiant.

“I’m crying because I am afraid for my baby. But if they think they can break us they are mistaken. If I had to, I will sacrifice my son and my husband, my father, my mother, my sister,” Najat says.

“Death of loved ones is hard but not harder than getting humiliated. And we will hold on to our faith and to our traditions till death.”

Darren Conway / BBC

Darren Conway / BBC

Najat says she is crying because she is afraid for her child

At the small CDF station in the village of Ferzoul, between orchards and vineyards, the Sun comes up after a cold night. The seasonal temperature is dropping here and most of Lebanon’s shelters for the displaced are full.

Samir arrives and I ask him how he copes with what he has seen.

“Some of the pictures are stuck in our head,” he says, adding that they will never go away.

He leans heavily on his faith.

“When you manage to keep one [person] alive, that will give you the strength to keep going,” he says.

“And this is a power that’s given from God and we're going to still do our job. Even if we were directly targeted, we say here in Lebanon, God will keep us safe and we have faith in God and he will keep us safe.”

1 month ago

6

1 month ago

6

English (US) ·

English (US) ·