Sudan’s power struggle in focus: former president Omar al-Bashir alongside rival generals Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (AI image generated using ChatGPT)

Sudan’s war did not begin with ideology or rebellion, but with a fallout between two men who once ruled together. When rival generals turned their guns on each other in April 2023, the capital Khartoum became the epicentre of a conflict that has since engulfed the entire country.What began as a power struggle at the top has spiralled into one of the world’s worst humanitarian disasters. Cities have been reduced to rubble, millions forced to flee their homes, and children pushed out of classrooms and into overcrowded camps. From Khartoum to the scorched towns of Darfur, the violence has exposed the deep fault-lines of a country trapped in a cycle of military takeovers and failed transitions.

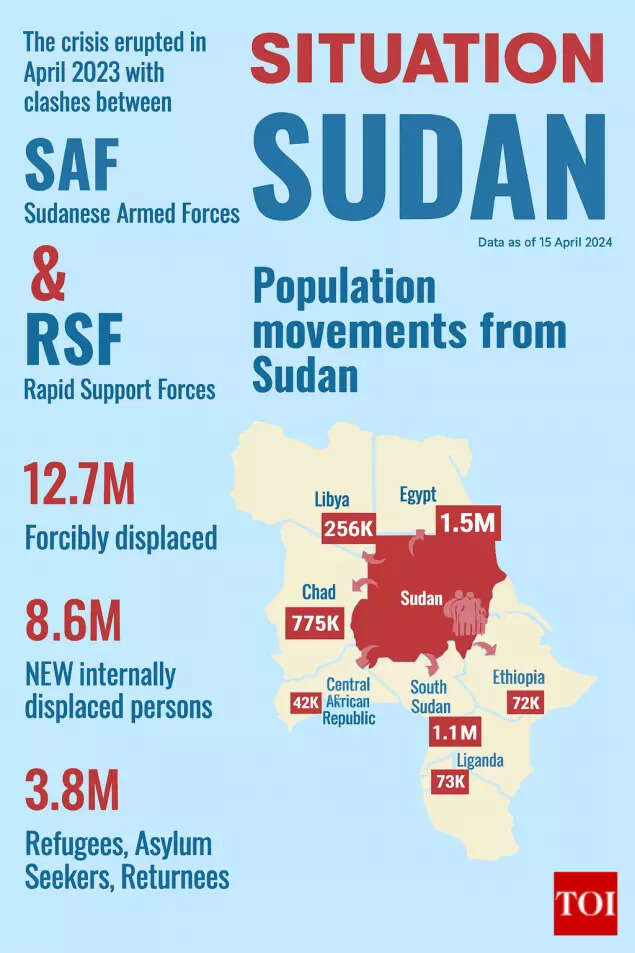

Situation Sudan (Credit: UNHRC)

As wars elsewhere dominate headlines, Sudan’s collapse has unfolded largely out of sight. The United Nations now describes it as the world’s largest displacement crisis: A catastrophe hiding in plain sight.

Two generals, one country: who is fighting whom?

At the heart of the war are two former allies who once ruled Sudan together. General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, head of the SAF, is Sudan’s de facto leader following the 2021 military coup. His rival, General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, widely known as Hemedti, commands the RSF and was once Burhan’s deputy.

The RSF traces its origins to the Janjaweed militias that terrorised Darfur in the early 2000s. Those militias, accused of mass killings and ethnic cleansing, were later formalised into a paramilitary force and gradually integrated into the state security apparatus. By the time Hemedti rose to prominence, the RSF had become a powerful, well-funded force with deep roots in Sudan’s gold trade and regional networks.

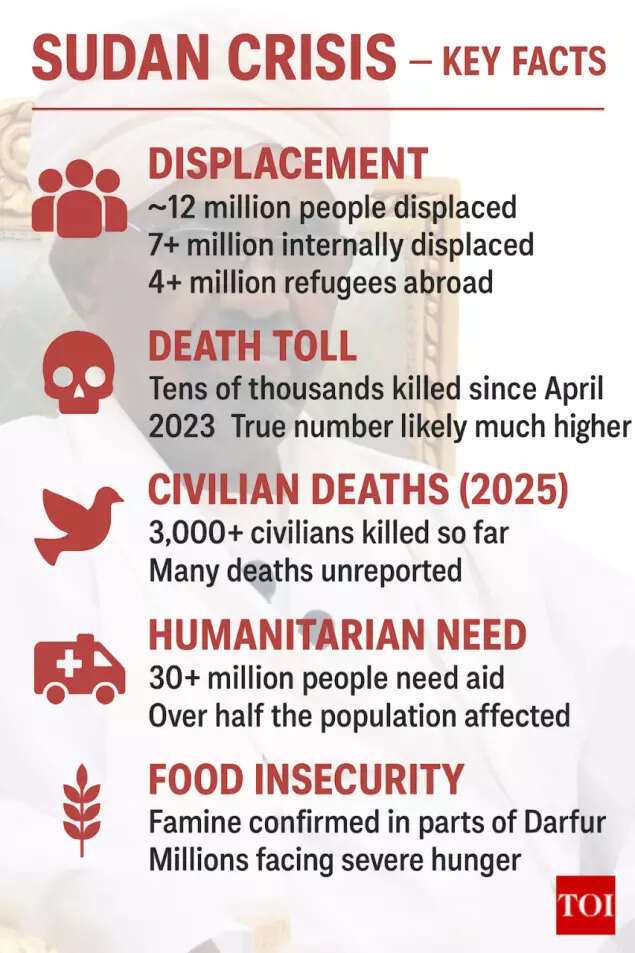

Key facts about Sudan crisis

Tensions between the two sides intensified during negotiations over Sudan’s transition to civilian rule. The central dispute was whether and how the RSF would be integrated into the regular army, and who would ultimately command the security forces. Talks collapsed, mistrust hardened, and the country slid into open war.The conflict has since hardened into territorial control. The SAF maintains its grip over parts of Khartoum, the north and east, including Port Sudan on the Red Sea.

The RSF dominates much of western Sudan, particularly Darfur and parts of Kordofan, after seizing key towns and supply routes. Neither side has achieved a decisive victory.

A nation uprooted

The human cost of Sudan’s war is almost unimaginable. Independent monitors and the United Nations report mass displacement on a scale rarely seen in modern conflicts. By late 2024, an estimated 10–12 million people had fled their homes, seeking shelter in makeshift camps inside Sudan or crossing into neighbouring Chad, South Sudan, Egypt and Ethiopia. By April 2024, the UN described Sudan as the site of the world’s largest displacement crisis, with 10.7 million people uprooted.

Displacement has triggered the near-total collapse of basic services. Aid agencies warn that more than 30 million Sudanese, well over half the population, now require emergency assistance as food shortages, disease outbreaks and exposure worsen. The UN World Food Programme has repeatedly warned that famine is looming without sustained aid, while UN experts estimate Sudan’s economy lost around $15 billion by the end of 2023 as industry and agriculture were devastated by fighting.Children have borne the brunt of the collapse. UNICEF says Sudan is now facing the world’s largest child displacement crisis, with more than four million children forced from their homes since April 2023. Education has effectively disintegrated: over 90% of school-age children, nearly 19 million, are no longer attending formal classes as schools are occupied, bombed or abandoned.

Healthcare has fared little better. In conflict-affected areas, roughly nine out of ten health facilities are no longer fully functional, having been bombed, looted or deserted by staff.

The breakdown of sanitation and routine care has fuelled outbreaks of cholera, measles and other preventable diseases. Malnutrition is rising sharply, with UNICEF estimating that around four million children are acutely malnourished, including nearly one million at risk of death without urgent treatment.

Darfur, again: Ethnic violence returns in plain sight

Nowhere has the violence been more extreme than in Darfur. As fighting spread westward, RSF forces and allied militias launched systematic attacks on non-Arab communities, reviving memories of the atrocities that shocked the world two decades ago.Satellite imagery, survivor testimony and independent investigations have documented entire neighbourhoods burned to the ground, particularly in West Darfur’s capital, El-Geneina. Thousands of civilians, many from the Massalit community were killed in targeted attacks. Survivors describe gunmen going door to door, executing residents and forcing others to flee at gunpoint.

Satellite images appear to show attempts to dispose of bodies after RSF seized Sudan's el-Fasher (Photo credit: AP)

The US State Department declared in early 2024 that RSF militias have “systematically murdered” members of certain ethnic groups and committed sexual violence in “an apparent genocidal campaign”.

(Human Rights Watch and the UN have amassed similar evidence). Remarkably, much of this destruction in Darfur was first detected by satellite. Imagery analysts noticed trails of smoke, fire-scarred villages, and ad hoc cemeteries swelling with bodies.

Remote sensing helped confirm thousands of unmarked graves and leveled homes in what some watchdogs call a “second Darfur” since the mid-2000s war.

Satellite imagery showing devastation in West Darfur (Photo credit: Human Rights Watch)

How did Sudan get here? A history of coups and broken promises

To understand why Sudan has fallen back into war, the bitter history must be recalled.

From independence in 1956, the country was riven by divisions. The predominantly Muslim-Arab north has repeatedly clashed with the African-Christian south. Sudan’s first leaders failed to choose between secular or Islamist governance, and southerners quickly rebelled. Early promises of federalism went unfulfilled, and successive northern regimes centralised power.By 1983, President Gaafar Nimeiry formally imposed Sharia law overnight across the country.

This abrupt Islamisation (the “September Laws”) alienated the mainly Christian and animist south and reignited war. A new southern rebel army, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A), fought for autonomy or independence for the next two decades. Civil conflicts erupted and stalled from 1955 to 1972 and then from 1983 to 2005.During those years the south bore some of the war’s worst bloodshed – villages were raided, civilians massacred (for example, in Bor and other towns) and children abducted or enslaved.

One infamous atrocity, the 1987 Dhein massacre, saw over a thousand Dinka villagers killed by Arab militias.

A history of violence

Oil played a bitter role: it was discovered in the south, but Khartoum built the only refinery (in the north) and exported all output to Port Sudan on the Red Sea. Southern Sudanese got virtually no benefit from their oil until very late in the peace process. In fact, South Sudan took 75% of Sudan’s oil reserves when it seceded in 2011.

Sudan’s petrol fields remain mostly in the south near the border. Pipelines and refineries run through the north, so whoever controls the government (Khartoum) controls the oil income.When the Comprehensive Peace Agreement of 2005 finally ended the north–south war, it paved the way to South Sudan’s independence but also left generational grievances unhealed. The north, meanwhile, has known little lasting democracy.

Sudan’s post-independence era has been marked by military coups every few years.For instance, in 1958 General Ibrahim Abboud ousted the civilian government. In 1969 Colonel Jaafar Nimeiry seized power. After popular uprisings, he was removed in 1985 and a brief civilian government returned – only to be overthrown again by Omar al-Bashir’s coup in 1989. Al-Bashir then ruled Sudan as an Islamist autocrat for 30 years.His fall in 2019 (under mass street protests) raised hopes for democracy. Yet even after Bashir’s ouster, another military council and a fractious civilian coalition failed to make a stable transition. Army generals remained deeply entrenched.In October 2021, General al-Burhan staged a coup, toppling the fragile joint government and sidelining key civilian leaders. A hurried deal even reinstated Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok, but he resigned in early 2022 amid ongoing strikes and mistrust.In this unsettled post-Bashir era, the SAF and RSF remained technically allies: Until their fierce break-up in 2023. The roots of the current war lie in that legacy of repeated coups and half-finished revolutions: each attempt at democracy so far has been cut short by military power grabs, leaving rival generals in a perpetual struggle.

When neighbours pick sides

Sudan’s war has not remained contained within its borders. Regional and international actors have backed rival factions, turning the conflict into a proxy struggle.Egypt, which has longstanding ties with Sudan’s military, is widely seen as supportive of the SAF, driven by concerns over border stability, Nile water security and deep institutional links between the two armies. The United Arab Emirates has been accused of backing the RSF, particularly due to its interests in Sudan’s gold trade and its desire to expand regional influence along the Red Sea, allegations the UAE denies.

Saudi Arabia has hosted peace talks and is generally viewed as closer to Burhan’s camp, prioritising stability on its western flank and security in Red Sea shipping lanes.

Sudanese soldiers from the Rapid Support Forces unit (Photo credit: AP)

Iran has reportedly supplied drones to the SAF, a move linked to Tehran’s efforts to reassert influence along the Red Sea corridor. Russia’s involvement has shifted over time, amid scrutiny of mercenary networks and Moscow’s broader competition for access and influence in Africa. Other regional players, including Eritrea, Chad, Turkey and Qatar, are also believed to exert varying degrees of influence.

The war the world stopped watching

Despite the scale of the catastrophe, Sudan’s plight has received comparatively little global attention. Human rights groups deplore what they call a “forgotten war”. Amnesty International called out the international community for treating Sudan as “neglected and ignored”. Even after a year of slaughter and displacement, no major power has imposed a credible peace plan. A UN Security Council resolution did finally call for a ceasefire – but its demands went unheeded, and the fighting intensified.

NGOs note that global media are focused elsewhere, and that appeals for aid have been vastly underfunded (by early 2024 the UN humanitarian appeal was only ~5% funded).

Women displaced from El-Fasher stand in line to receive food aid (Photo credit: AP)

With relief funds drying up, schools remain shut and clinics closed. Over 19 million children are out of school; UNICEF warns Sudan now has “one of the worst education crises in the world”. Food aid is intermittent, and epidemics spread unchecked in some camps.

The World Food Programme has repeatedly warned of famine, yet funding gaps persist. As one diplomat put it bluntly, “Sudan has become a buffet table for external interests, with the wounded people largely forgotten.

”

Why Sudan keeps falling back into war

Why has Sudan plunged time after time into this abyss? The short answer is that overlapping fault-lines: Ethnic, religious, economic, plus a legacy of authoritarianism, have never been fully reconciled.

Islamisation policies (from Nimeiry’s 1983 Sharia decree through Bashir’s theocratic rule) alienated non-Muslim communities and southerners for decades. The question of the south Christian/animist by faith was never resolved except by partition, and lingering bitterness remains over resources and identity. The Janjaweed phenomenon first emerged precisely because governments armed one group of Sudanese Arabs against others, entrenching ethnic hatred.

Every swing of the power pendulum – from one military junta to another – has more deeply fragmented society.

In practical terms, Sudan’s two armies have roughly equal strength and are locked in a vicious deadlock over who will dominate the security forces. Neither side trusts the other to disarm, and each fears that laying down arms would mean marginalisation or reprisal. Political dialogue has long been impossible. Efforts to integrate the militias or build a unified army were always going to be fraught – as even the Saudi-hosted Jeddah talks showed. Add to this the economic angle (control of lucrative gold mines and the flow of oil/gas revenues), and you have a recipe for endless conflict.Sudan’s war is often framed as an intractable civil conflict, but its roots are painfully familiar: unchecked military power, failed transitions and a political class that has repeatedly placed survival above the state. Ending the war will require more than ceasefire statements, it will demand sustained international pressure, accountability for atrocities and, above all, the return of civilians to the centre of Sudan’s future.

3 weeks ago

11

3 weeks ago

11

English (US) ·

English (US) ·