The ancient Bialowieza Forest stretches across eastern Poland and Western Belarus, pre-dating both countries. As Europe’s largest primeval forest, it is home to many rare ecosystems and thousands of species, including more than 800 European bison. The forest was declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1979.

Centuries-old trees create a thick canopy which gives the depths of the forest an otherworldly feeling. Yet lately, the immense wilderness has been marred by the rumbling of sand trucks as Poland rushes to reinforce its security infrastructure along the border with Belarus.

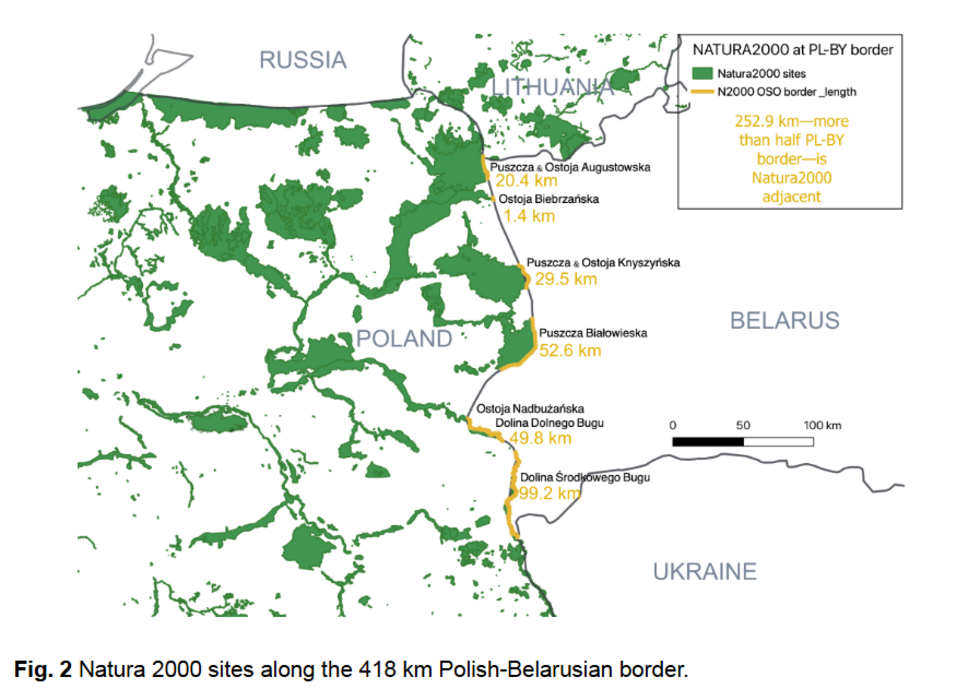

Until recent years, the forest’s isolated location on the fringes of Europe facilitated its preservation. Yet geopolitical tensions beginning in 2021 have begun to threaten the forest's exceptional biodiversity. When the Belarusian dictator Aleksander Lukashenko opened a new migratory route by encouraging migrants and refugees to cross illegally into Poland, the Polish government reacted with pushbacks and the construction of a 186-kilometre fence along its border with Belarus in 2022.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine strengthened Poland’s will to boost its resilience in case of war. It has become a key hub for European and NATO defence efforts. It is NATO’s largest contributor relative to its size and a participant in the EU’s SAFE program to boost defence readiness. The country is also the eastern border of NATO and the European Union.

One of Poland's current defence projects is known as "The Eastern Shield": launched in 2024 and planned for completion by 2028, this fortification covers a 700-kilometre stretch of Poland’s border with Belarus and Russia’s Kaliningrad Oblast. The €2.4 billion project to bolster border security is occasionally called the "Tusk Line", a nod to Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk and the renowned Maginot Line constructed by France in the 1930s to discourage a Nazi German invasion during WWII.

But researchers now fear the military buildup is harming the forest’s unique ecosystems and wildlife.

The plan is “being executed now in the form of paving the border road [between Poland and Belarus]”, said Katarzyna Nowak, a researcher and author of a recent report on the ecological consequences of state border barriers.

Bialowieza Forest runs along the Polish-Belarusian border for about 53 kilometres. “Of that, about 10 kilometres is the national park, [which] has managed to negotiate that the road will not be paved along the park. But again, that’s only 10 kilometres, and the rest – 40-some-kilometres – is being paved as we speak,” said Nowak.

The road will “make it even challenging to reconnect the two sides of the forest in the future”, according to the researcher, adding that the transboundary nature of the forest is under threat through the addition of further border infrastructure.

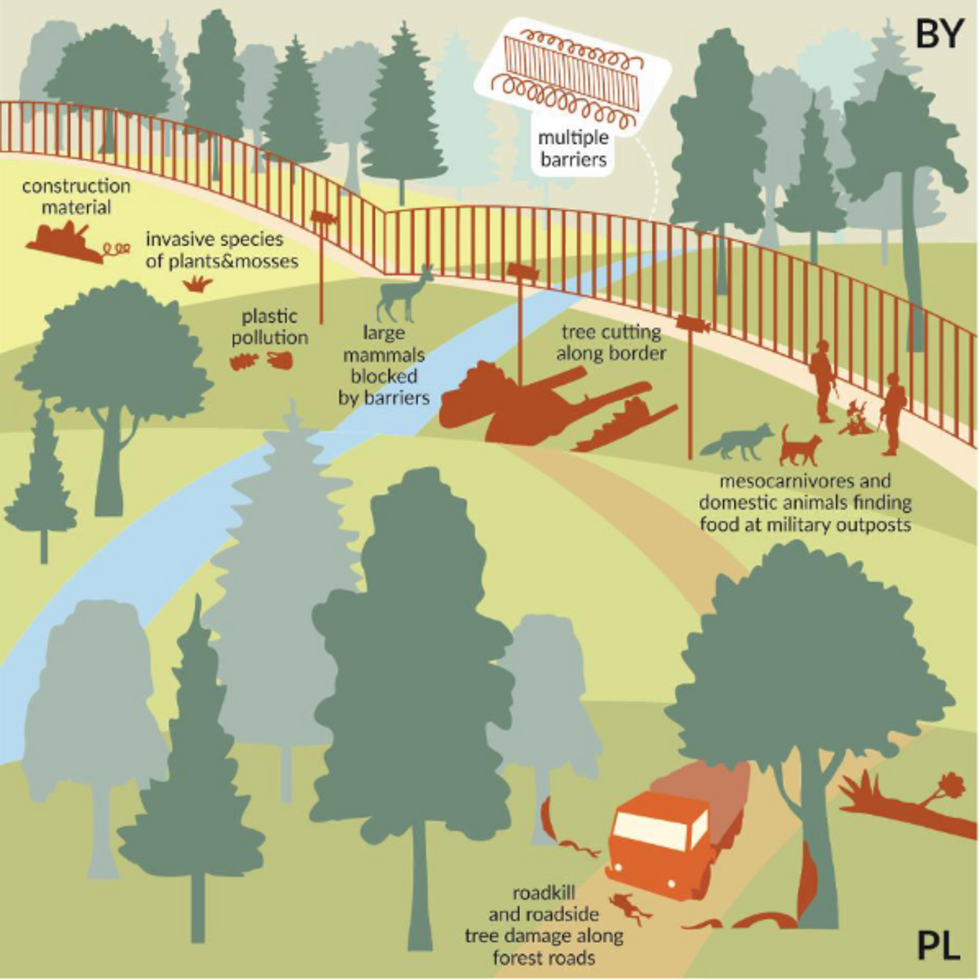

“We have multiple barriers on the border: a forest net and razor wire, the road that’s being paved, and then the main, concrete razor-wire barrier on the Polish side. Then we have a fence from the Soviet era on the Belarusian side, as well as a road,” said Nowak.

The militarisation of the border in the name of national security is having an impact on animal movement. In videos provided by the Polish Border Guard and highlighted in Nowak’s report, a herd of wild boar crossing the Polish-Belarusian border in 2014 continued unimpeded, while a roe deer and wolf in 2022 were stopped by the wall.

In addition to blocking animal movements, the paving of the road will likely have other unanticipated consequences on wildlife. “Other animals, like foxes or pine martens have learned to cross those barriers, but now they are going to have to contend with probably faster traffic along this road, which might lead to roadkill,” said Nowak.

Smaller animals, “like amphibians, such as frogs or snakes, use roads to warm themselves, because the road surface is going to heat up come spring and summer, and so we can expect that those animals will get run over and killed”, said the researcher.

Read moreTo defend against Russian tanks, Finland and Poland consider restoring wetlands

Paving a road in a transboundary world heritage site is obviously harmful from an ecological point of view. Yet even from a security standpoint, the man-made border fortifications are causing concern. Some experts in forest ecosystems have called for the government to use the region’s natural resources as a means of defence, like biologists from the Polish Academy of Sciences (PAN), which called on the government to invest in restoring natural wetlands or reforestation as a barrier against military aggression.

“When you pave a road, [it] facilitates access across this entire, paved segment of road which is around 200 kilometres,” said Nowak. “You are not actually using the natural habitat along the border to impede your enemy. You’re just creating an access road, not just for yourself, but for your enemy.”

Bialowieza Forest, once a major destination for biologists conducting research on animal behaviour, is under pressure like never before. The sound of sand trucks moving back and forth, heavy machinery, and of materials being transported through the forest, can be deafening. “People may not like to use forest roads if they have to constantly get out of the way of the big sand trucks,” said Nowak.

“We know this from a survey we did when the closed zone was still in effect,” said the researcher. Tensions at the border in 2021 led the president at the time, Andrzej Duda, to declare a state of emergency in the area and prohibit access to the area encompassing border infrastructure.

Going to the forest less “affects people’s connection to the nature here, it changes the way they use the forest, this can ultimately shape the attitudes people have towards the forest into the future and obviously the way they may steward it," Nowak added.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·