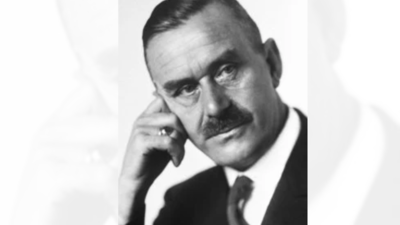

Thomas Mann (Image credit: Nobel Prize website)

One of the greatest writers of the 20th century, Thomas Mann's literary genius reflected a life spent wandering between diverse worlds, especially after escaping Germany in the early 1930s.Mann rose to global fame when in 1929 he won the Nobel Prize for Literature — primarily for for his great social novel, "Buddenbrooks" (1901), but also for his fiction masterpiece, "The Magic Mountain" (1924).But during and after the Nazi dictatorship from which he escaped, Mann wrote political essays and delivered radio speeches to his compatriots about the German "catastrophe" that led to the Holocaust. These strident views were often reflected in his work.

Early rise to literary prominence:

Thomas Mann was born on June 6, 1875 in Lübeck, northern Germany, to a merchant family. He was raised with four siblings, and as a schoolboy wrote his first prose sketches and essays — even if he once repeated a grade and was deemed as only a "satisfactory" student of German.His artistic aspirations did not fit in well in the middle-class mainstream, and his passion for literature saddened his merchant father. This sensitive bohemian's struggle to carry on the family's time-honored business partly inspired Mann's first work, "Buddenbrooks."

When his father died in 1891, Mann left school before completing his A-levels and moved to Munich with his family. Living off his father's inheritance, he soon began to work as a freelance writer and had ambitions to become a journalist.At the age of 22, after spending time in Italy with his brother Heinrich, Mann started to pen "Buddenbrooks," which was subtitled "a family's decline" in German. The semi-autobiographical debut novel about the downfall of a wealthy merchant family was such a success that Mann was able to henceforth live off his writing.

War and sibling rivalry:

Other works soon followed, initially the novella collection "Tristan" (1903), which also includes "Tonio Kröger," a story about the contrast between artist and citizen, spirit and life.In 1905, the novelist married Katia Pringsheim, the daughter of a wealthy Munich family of scholars. He was also attracted to young men, though this did not seem to bother Katia. The couple had six children. Some of them later followed in their father's footsteps and became writers.The First World War (1914-1918) began and Thomas fell out with his brother Heinrich, by then also a successful author, over Germany's role in the war. Heinrich published an anti-war pamphlet, while Thomas defended the empire and its war policy.It was not until 1922 — by which time Germany had lost the war and democracy arrived with the Weimar Republic — that Thomas Mann changed his stance and supported democratization.Mann's Nobel Prize for Literature in 1929 was a huge success for the writer, but long before the outbreak of the following world war, Mann sensed danger.He expressed opposition to the rising Nazi party and made a fiery plea against authoritarianism and in favor of social democracy in 1930.Thus in the spring of 1933, barely a month after Adolf Hitler became German chancellor, Mann did not return to Germany from a lecture tour of Europe.

He settled in Switzerland, his family following after the Nazis confiscated the Mann house in Munich along with the writer's bank accounts.The first volume of "Joseph and His Brothers" was subsequently published after it was smuggled out of Germany — the four-part novel describes the incarnation of the biblical figure Joseph.After Mann denounced Nazi policies in a public letter in 1936, his German citizenship was revoked, along with his honorary doctorate from the University of Bonn.

The Nazis had robbed him of his fortune, and fame.

Emigration to the US and return to Europe:

Thomas and Katia Mann emigrated to the US in 1939, after Germany's invasion of Czechoslovakia. Mann took up a guest professorship at a university in Princeton. When a reporter asked him on his arrival how he felt about going into exile, Mann replied: "Where I am is Germany! I carry my culture within me."From 1940 onwards, Thomas Mann called on the Germans to resist. The British radio station BBC broadcast his monthly radio speeches to his former homeland, bypassing German censorship.

In over 60 broadcasts, he spoke to the conscience of his compatriots, and did not shy away from the mass murder of the Jews.Mann's public letter of 1945, "Why I will not return to Germany," held all Germans responsible for the atrocities of the Nazi era. But some critics denied him the right, as an exile, to pass judgment on life under Hitler.Some could not comprehend Mann's comment that the fire bombing of German cities was justified.

"Everything must be paid for," he said. The writer continued this theme in his novel "Doctor Faustus," published in 1947. It tells of the composer Adrian Leverkühn's pact with the devil, and is a metaphor for the social conditions that made National Socialism possible.But not everything was going well in the USA either: as a "suspected communist," Mann had to testify to the House Un-American Activities Committee, which called him "one of the world's foremost apologists for Stalin and company."The writer left America again in 1952, but he was not drawn to either of the two German states and instead returned to Switzerland, where he died in Zurich Cantonal Hospital on August 12, 1955 at the age of 80.With his literature, but also with his steadfastness in the face of fascism, Thomas Mann set a courageous example and a legacy that remains.

1 month ago

17

1 month ago

17

English (US) ·

English (US) ·