The crisis in Venezuela

Christmas came early this year in Venezuela. The season officially began October 1, as decreed by the country's authoritarian president, Nicolás Maduro. "I am going to declare the advancement of Christmas to the first of October," he said.

The absurdity would be laughable if this weren't the perfect snapshot of Venezuela's black-is-white, dystopian unreality, an oil-rich country so devastated economically that it can't even keep the lights on … where life is so unlivable that a quarter of its population (nearly 8 million people) has fled.

"He needed a distraction," said former New York Times journalist William Neuman. "It's bread and circuses."

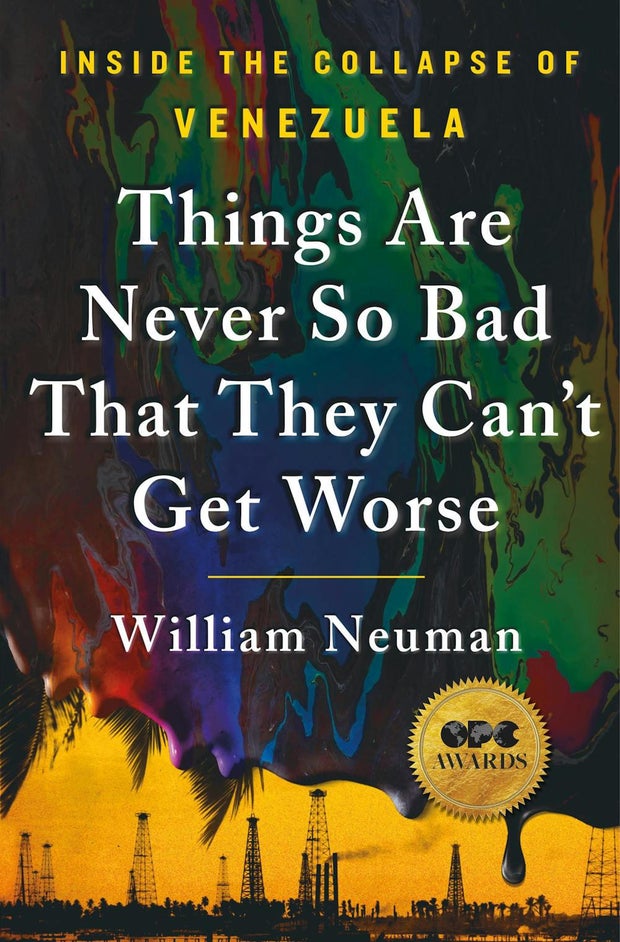

The title of Neuman's book about Venezuela says it all: "Things Are Never So Bad That They Can't Get Worse." "Everybody knows that he's lost the election," he said. "He's the emperor who has no clothes."

St. Martin's Press

St. Martin's Press

In July, Venezuela, with a history of on-again, off-again democracy, held elections. Maduro claimed he had been re-elected, but in a bold act of defiance, the opposition produced voting machine tallies proving that Edmundo González had actually won the presidency, by better than a 2-to-1 margin. Impartial election observers agreed.

Maduro called out the military to enforce his election denial. González was told to leave the country, or else. (He turned up in Spain.) In the ensuing chaos, at least two dozen people were killed, and more than 2,000 detained.

- Venezuela relying on "most violent" repression after Nicolás Maduro's claimed election win, U.N. experts say

- U.S. sanctions Maduro's allies after disputed Venezuela presidential election

- U.S. recognizes opposition candidate Edmundo González as winner of Venezuelan presidential election

María Corina Machado, the face of the opposition, who would have run for president herself if Maduro hadn't barred her, is in hiding. "I've been accused of terrorism," she told "Sunday Morning" via Zoom. "The dictatorship has said that they're looking for me, and that they want to get me as soon as possible."

So, how could a country sitting on the largest oil reserve in the world end up like this? According to Neuman, "It rained money. They spent it, wasted it, and stole it. It stopped raining, and the people went hungry. And that's essentially what happened in Venezuela in a nutshell."

Venezuela has been producing oil since 1914, but what's known as "the resource curse" really set in when the charismatic and controversial Hugo Chávez was elected president in 1998. When he took office, the price of oil was $7 a barrel, Neuman said: "Within several years, it gets to over $120 a barrel, so Chávez was very fortunate, because he comes in just at the beginning of this great commodities boom."

Chávez spent huge sums of oil money on social programs, and borrowed even more, plunging his country into debt. But ordinary Venezuelans felt rich and heard for a change.

The United States was his favorite bogeyman. At the United Nations in 2006, Chávez called President George W. Bush "the devil."

When Chávez died of cancer in 2013, his hand-picked successor was Nicolás Maduro, who wasn't so popular, or so lucky. Oil prices crashed; inflation reached an inconceivable 300,000%.

Maduro met public discontent with repression, and millions left the country.

Looking at the map of the Venezuelan exodus since 2014, the United States is fourth among destinations. Just over 750,000 have either been granted temporary protected status in the U.S., or have applied. So, Venezuela's crisis is here, at our doorstep, in our cities.

CBS News

CBS News

Niurka Meléndez left in 2015. "We are broken," she said. "We were broken as a country ... no institutions, no freedom."

With temporary protected status, she and her husband can live and work in the United States legally. They founded VIA (Venezuelans and Immigrants Aid), a volunteer organization helping new arrivals in New York City.

Meléndez introduced us to one woman who left Venezuela with eight members of her family, including her four small children. She's afraid, even here, to disclose her name. "When an armed group named Colectivos came to my house, they took everything that I had," she said. "They took even the blender, everything, my computer, everything. And then they hit us because we didn't have the money, the exact money – they were asking for $500. I didn't have that amount."

So, they crossed the Darién Gap, risking their lives. Since its contested election in July, Venezuela has resumed the human hemorrhage of its people – has resumed exporting its crisis.

- Making the treacherous journey north through the Darién Gap ("Sunday Morning")

María Corina Machado said, "Venezuela is today the biggest migration crisis in the world. Almost 25% of the population that remains in Venezuela [is] thinking about leaving. This is huge. This could be five, six millions Venezuelans leaving the country."

For more info:

- "Things Are Never So Bad That They Can't Get Worse: Inside the Collapse of Venezuela" by William Neuman (St. Martin's Press), in Hardcover, eBook and Audio formats, available via Amazon, Barnes & Noble and Bookshop.org

- VIA (Venezuelans and Immigrants Aid)

Story produced by Wonbo Woo. Editor: David Bhagat.

See also:

- America's long, fractured history of immigration ("Sunday Morning")

- Immigration laws raising issues for Florida growers ("Sunday Morning")

- Immigration deal hangs in the balance as U.S. border crisis divides the country ("Sunday Morning")

English (US) ·

English (US) ·